CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Self-Arrest

CHAPTER 2

From Rockford to Rainier

CHAPTER 3

The Long Road to Everest

CHAPTER 4

Twofers and True Love

CHAPTER 5

Time to Say Good-bye

CHAPTER 6

Closing In

CHAPTER 7

Nemesis: Annapurna

CHAPTER 8

The Last Step

EPILOGUE

Other Annapurnas

For Paula, Gilbert, Ella, and Anabel

the best reasons in the world for coming home

And in memory of my great partners

Rob Hall, Scott Fischer, and Jean-Christophe Lafaille

Self-Arrest

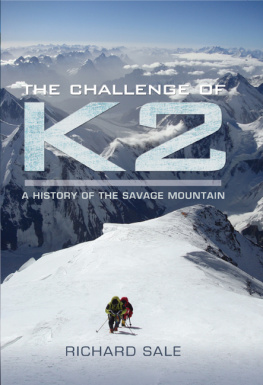

A t last things seemed to be going our way. Inside our Camp III tent, at 24,300 feet, Scott Fischer and I crawled into our sleeping bags and turned off our headlamps. The next day, we planned to climb up to Camp IV, at 26,000 feet. On the day after, we would get up in the middle of the night, put on all our clothing, grab our gear and a little food, and set off for the summit of K2, at 28,250 feet the second-highest mountain in the world. From Camp IV, the 2,250 vertical feet of snow, ice, and rock that would stretch between us and the top could take as long as twelve hours to climb, since neither Scott nor I was using supplemental oxygen. We had agreed that if we hadnt reached the summit by two P.M., wed turn aroundno matter what.  It was the evening of August 3, 1992. Fifty-four days earlier, we had started our hike in to base camp on the Baltoro Glacier, which we had reached on June 21. Before the trip, even in my most pessimistic scenario I had never imagined that it could take us more than six weeks just to get in position for a summit push. But this expedition had seemed jinxed from the startby hideous weather, by minor but consequential accidents, by an almost chaotic state of disorganization within our team.

It was the evening of August 3, 1992. Fifty-four days earlier, we had started our hike in to base camp on the Baltoro Glacier, which we had reached on June 21. Before the trip, even in my most pessimistic scenario I had never imagined that it could take us more than six weeks just to get in position for a summit push. But this expedition had seemed jinxed from the startby hideous weather, by minor but consequential accidents, by an almost chaotic state of disorganization within our team.

As usual in the midst of a several-day summit push at high altitude, Scott and I were too keyed up to fall asleep. We tossed and turned in our sleeping bags. Then suddenly, around ten P.M., the radio in our tent crackled to life. I turned on my headlamp, grabbed the walkie-talkie, and listened intently. The voice on the radio was that of Thor Kieser, another American, calling from Camp IV, 1,700 feet above us. Hey, guys, Thor blurted out, his voice tense with alarm. Chantal and Alex arent back. I dont know where they are.

I sighed in pure frustration. In the beam of my headlamp, I saw a kindred expression on Scotts face. Without exchanging a word, we knew what this meant. Our summit push was now on indefinite hold. Instead of moving up to Camp IV to get into position, the next day we would find ourselves caught up in a searchand possibly a rescue. The jinx was alive and well.

On August 3, as Scott and I had made the long haul from base camp up to Camp III (a grueling 7,000 feet of altitude gain), Thor Kieser, Chantal Mauduit, and Aleksei Nikiforov had gone for the summit from Camp IV. Chantal, a very ambitious French alpinist, had originally been part of a Swiss team independent from ours. When all of her partners had thrown in the towel on the mountain and left for home, she had stayed on (illegally, in terms of the permit system) and in effect grafted herself onto our group. She was now the only woman on the mountain. Alekseior Alex, as we called himwas a Ukrainian member of the Russian quintet that made up the core of our team.

That morning, Alex and Thor had set out at five-thirty A.M ., Chantal not until seven. These starting times were much later than Scott and I would have been comfortable with, but the threesome had been delayed because of high winds. Remarkably, climbing without bottled oxygen, Chantal caught up with the men and surged past them. Struggling in the thin air, Thor turned back a few hundred feet below the summit, unwilling to get caught out in the dark. Chantal summited at five P.M ., becoming only the fourth woman ever to climb K2. Alex topped out only after dark, at seven P.M .

The proverbial two P.M . turn-around time isnt an iron-clad rule on K2 (or on Everest, for that matter), but to reach the summit as late as Chantal and Alex did was asking for trouble. And trouble had now arrived.

On the morning of August 4, as Scott and I readied ourselves for the search and/or rescue mission that would cancel our own summit bid, we got another radio call from Thor. The two missing climbers had finally showed up at Camp IV, at seven in the morning, but they were in really bad shape. Chantal had been afraid to push her descent in the night and had bivouacked in the open at 27,500 feet. Three hours later, Alex had found her and talked her into continuing the descent with himpossibly saving her life.

Staggering through the night, the pair had managed to stay on route (no mean feat in the dark, given the confusing topography of K2s dome-shaped summit). But by the time they reached the tents at Camp IV, Chantal was suffering from snow blindness, a painful condition caused by leaving your goggles off for too long, even in cloudy weather. Ultraviolet rays burn the cornea, temporarily robbing you of your vision. Chantal was also utterly exhausted, and she thought she had frostbitten feet. In only marginally better shape, but determined to get down as fast as possible, Alex abandoned Chantal to Thors safekeeping and pushed on toward our Camp III. He just said, Bye-bye and took off.

Thor himself was close to exhaustion from his previous days effort, but on August 4 he gamely set out to shepherd a played-out Chantal down the mountain. Its an almost impossible and incredibly dangerous task to get a person in that kind of shape down slopes and ridges that are no childs play for even the freshest climber. Thor had scrounged a ten-foot hank of rope from somewherethats all he had to belay Chantal with, and maybe to rappel.

Over the radio to us, Thor had pleaded, Hey, you guys, I might need some help to get her down. So Scott and I had made the only conscionable decision: to go up and help.

As we were getting ready, we watched as Alex haltingly worked his way down the slope above, eventually stumbling toward camp. We went up a short distance to assist him, then helped him get into one of the tents, where we plied and plied him with liquids, since he was severely dehydrated. Meanwhile, surprisingly, he didnt show any concern for Chantal.

Going to the summit, both he and Chantal had pushed themselves over the edge, driven themselves to their very limits. It happens all the time on the highest mountains, but its kind of ridiculous.

To make matters worse, on August 4 the snow conditions were atrocious. Same with the weather: zero visibility. Scott and I tried to go, made it up the slope for a couple of hours, then had to turn around and head back to camp. We made plans for another attempt the following day.

We were in radio communication with Thor. Hed started to bring Chantal down to Camp III, but he only got partway. They had to camp right in the middle of a steep slope, almost a bivouac, though Thor had been smart enough to bring a tent with him.

Next page

It was the evening of August 3, 1992. Fifty-four days earlier, we had started our hike in to base camp on the Baltoro Glacier, which we had reached on June 21. Before the trip, even in my most pessimistic scenario I had never imagined that it could take us more than six weeks just to get in position for a summit push. But this expedition had seemed jinxed from the startby hideous weather, by minor but consequential accidents, by an almost chaotic state of disorganization within our team.

It was the evening of August 3, 1992. Fifty-four days earlier, we had started our hike in to base camp on the Baltoro Glacier, which we had reached on June 21. Before the trip, even in my most pessimistic scenario I had never imagined that it could take us more than six weeks just to get in position for a summit push. But this expedition had seemed jinxed from the startby hideous weather, by minor but consequential accidents, by an almost chaotic state of disorganization within our team.