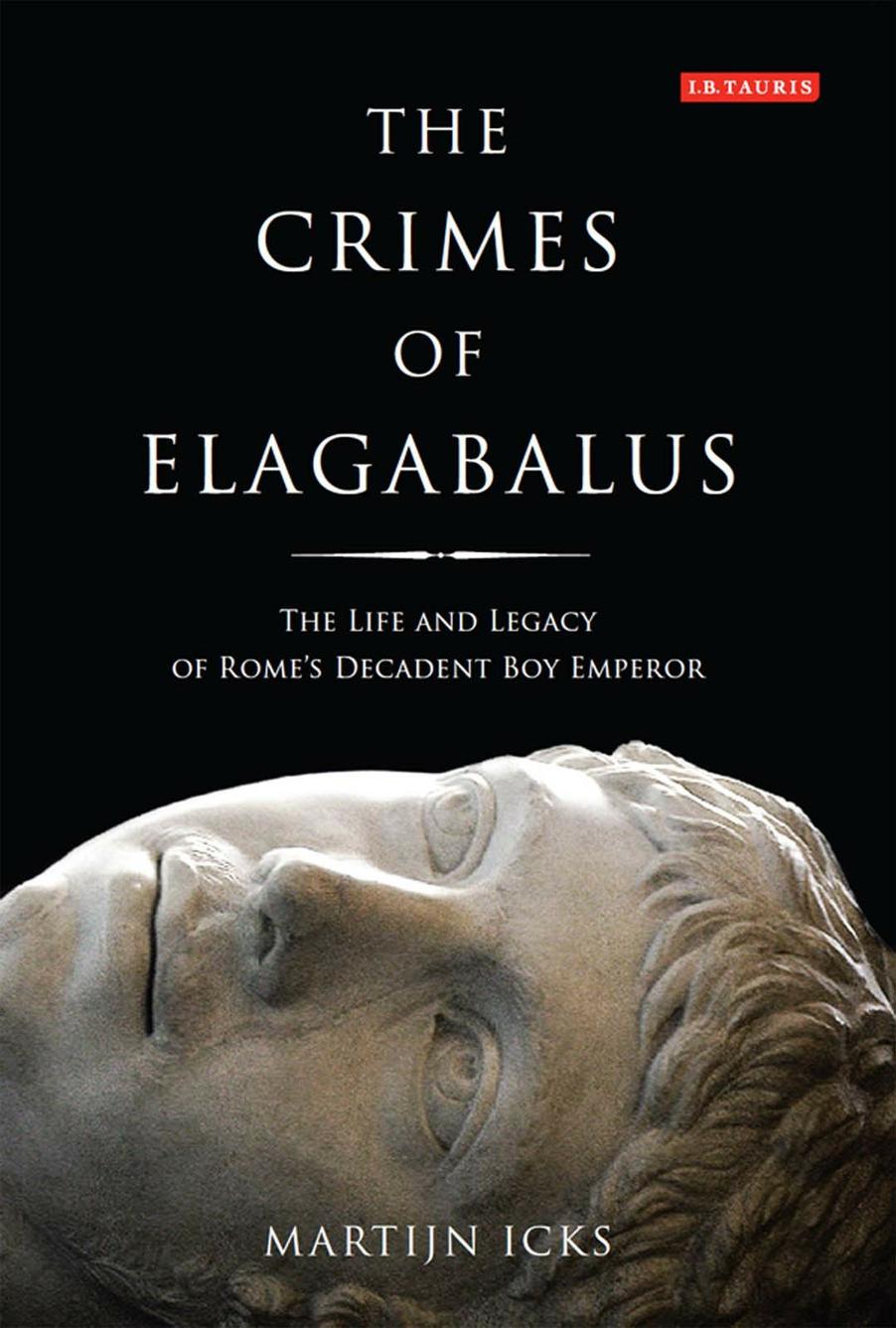

Martijn Icks is a Marie Curie fellow at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universitt Heidelberg, Germany. He was previously Lecturer in History and Literature Studies at the University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands and obtained his PhD cum laude in 2008.

This is a clear and well-organised account written in a lively and approachable way. It is not a routine imperial biography, but a much wider study encompassing the nature of religious belief, culture and ethnicity, the presentation of the imperial image and the response to this in Rome and the provinces. An important and original aspect is the description of the dissemination of classical culture and the reception of Rome in later periods, and in particular the changing image of Elagabalus in opera, drama and fiction.

Brian Campbell, Professor of Roman History,

Queens University Belfast

I quote in elegiacs all the crimes of Heliogabalus

William Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, The Pirates of Penzance (1879)

It is absurd, purely grotesque, this caricature we have of Antonine; perhaps that is why the world has left him alone, that they may gaze the longer on a mask that allures.

John Stuart Hay, The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus (1911)

History is something that never happened, written by a man who wasnt there.

Anonymous

Published and reprinted in 2011 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright Martijn Icks 2011

The right of Martijn Icks to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 84885 362 1

eISBN: 978 0 85773 026 8

Typeset in Calisto by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is an interesting thought that Elagabalus ruled the Roman world for about the same time as it took me to write this book. Naturally, the problems and challenges faced by the average scholar of ancient history shrink into insignificance when measured against the worries of a Roman emperor especially if that emperor happens to be Elagabalus, who had so much to worry about. Nevertheless, the road I have travelled for the past four years has not been without its bumps and pitfalls. Many guides have helped me to find my path. Here, I want to give them a well-earned moment in the sun.

Luuk de Blois has played a key role from the very start, supporting me through the writing of this book with an endless supply of valuable comments and good cheer. I admire him for his encyclopaedic knowledge and his unwavering devotion to the people working under his guidance. Eric Moormann has proved an excellent guide in the worlds of art and archaeology. His extensive remarks on my drafts bespoke a sharp eye for even the smallest detail, from which I have benefited greatly. Last but not least, Sophie Levie was a welcome contributor to the team. As an expert in the field of modern literature, she prevented me from making many mistakes and corrected many more.

I very much enjoyed my year at Brasenose College, Oxford, where I had stimulating discussions with many outstanding scholars. I am much indebted to Alan Bowman, who commented on the drafts of my first three chapters. Ted Kaizer made time for me on several occasions, helping me to understand the Roman Near East. I also have fond memories of my meetings with Ittai Gradel, who was always happy to discuss the naughty boy Elagabalus while treating me to several cups of coffee. A year later, when I went to Paris, Sgolne Demougin was kind enough to receive me as a guest at the cole Pratique des Hautes tudes. The three months I spent researching in the Bibliothque Nationale were of great value for writing the sixth chapter.

Still, most of the work was done at Nijmegen, where I had the good fortune of sharing an office with Marloes Hlsken and Erika Manders. Their pleasant company made my time on the tenth floor of the Erasmus building a lot more gezellig . The same goes for all those other wonderful people at the History department, in particular my fellow ancient historians. Luuk and Erika have already been mentioned; I want to add Lien Foubert, Janneke de Jong, Nathalie de Haan, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, Inge Mennen, Jasper Oorthuys, Sanne van Poppel, Rob Salomons, and Danille Slootjes to the list. Nobody could wish for a better team of colleagues, and indeed I never have.

Without Vincent Hunink, this thesis would probably not have been written at all. He may not be aware of the vital role he played, but it was his Dutch translation of the Vita Heliogabali which first set me on the trail of this weird and fascinating emperor. I hope he will enjoy my book as much as I enjoyed his.

Jason Hartford performed the tedious task of correcting my English, which he has done with much accuracy and humour. His witty remarks in the margin never failed to put a smile on my face. For that, and for everything else, I thank him.

My parents were always there in the background to support me, even if the object of my research must have seemed a tad obscure to them. I owe them more than I can express in this short paragraph. Whenever I got too carried away by my findings, my brother Remco was sure to put things into perspective, reminding me that the study of history is nothing but dragging up old cows in the end.

Many others deserve to be mentioned. A mere list of names does no justice to all the people who have been so kind, providing me with suggestions, criticism and references, but for practical reasons I will keep it short. Many thanks are due to Nicole Belayche, Stphane Benoist, Anthony Birley, Pierre Cosme, Ja Elsner, Christophe Fricker, Willem Frijhoff, Sky Gilbert, Andr Hanou, Jan Hartman, Johan van Heesch, Chris Howgego, Willy Jansen, Ellen Kraft, Andreas Kropp, Inger Leemans, Barbara Levick, Marco Mattheis, Michael Meckler, Fergus Millar, Stephan Mols, Frits Naerebout, Marc van der Poel, Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado, Bert Smith, Natascha Veldhorst, Jessica Walker, Jan Waszink, Ryan Wei, Caroline de Westenholz, Christiaan Willemsen, and anybody else whom I may have inadvertently forgotten, but who made a valuable contribution to my study of the priest-emperor in one way or another.

This project would not have been possible without the support of the Radboud University of Nijmegen, which provided the necessary funds, working space and all the facilities I needed to carry out my research. In addition, I have received grants from the VSB Foundation and Dr Hendrik Mullers Vaderlandsch Fonds, allowing me to spend valuable research time in Oxford and Paris.

The author of this work claims sole responsibility for any remaining mistakes. Should this study be hacked to pieces by the critics and suffer damnatio memoriae, the blame is mine for not paying enough heed to the wise words of many advisers.

INTRODUCTION

From Nero to Caligula, the Roman Empire is credited with many colourful, eccentric and notorious emperors. Among these, Elagabalus (also known as Heliogabalus) occupies a prominent place. Infamous anecdotes about this remarkable ruler abound, from his devotion to an exotic god, his conduct of human sacrifices and his insatiable sexual appetite, to such noteworthy feats as the institution of a womens senate and the building of a suicide tower. Even if only a fraction of these tales is true, Elagabalus must have been one of the most intriguing and unusual characters ever to sit on the Roman throne.