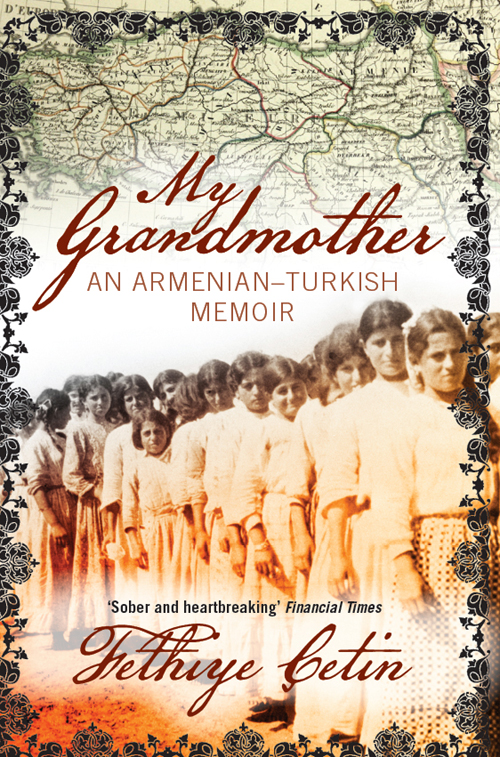

MY GRANDMOTHER

MY GRANDMOTHER

An Armenian-Turkish Memoir

FETHIYE ETIN

Translated by Maureen Freely

This paperback edition first published by Verso 2012

First published by Verso 2008

Verso 2008

Translation Maureen Freely 2008

Introduction Maureen Freely 2008

First published as Anneannem: Anlati

Metis Yayinlari 2004

All illustrations in this book have been reproduced courtesy of the author

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

13 57 9108 64 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Epub ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-925-6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

I would like to thank my dear Aye, Nadire, Necmiye, Zeynep, Zehra and Handan, who gave me the courage to write this book, and did everything in their power to help me persevere, casting aside any excuse I made to shirk from the task; if it hadnt been for you, this book would never have come into being. I am so fortunate to know you, and to have you as my friends.

Preface

Maureen Freely

When victorious generals sit down to dictate history, their greatest privilege is to choose what to leave out. Thus, Europeans know little or nothing about the 1920 Treaty of Svres, which, had it been ratified, would have carved up most of what was left of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War One. Izmir and the Aegean coast would have passed to the Greeks; a large part of eastern Anatolia might have become part of an independent Armenia, leaving only Istanbul and northern Anatolia in Ottoman hands. But since much of this region was under Allied occupation in 1920, it, too, had taken on the aspect of a European colony. And so it might have remained, if Mustafa Kemals armies had not risen up to reclaim the lands that now define the Republic of Turkey.

But in 1927, when Kemal sat down to write the official history of its birth, Svres still cast a long shadow. It was the future that might have been, had Europe and Anatolias Christian minorities had their way. It is through this prism that four generations of Turkish schoolchildren have been taught to view the catastrophes of the last years of the Ottoman Empire, when Anatolia was between one quarter and one third Christian. They are not told that the triumvirate then in charge of the empire wished to Turkify Anatolia by reducing that population to a level that would render it politically insignificant. Nor are they told that the same cadre aimed to relocate and resettle Anatolias many Muslim minorities Kurdish, Arab, Circassian, Georgian, Laz, Albanian, Bulgarian, amongst others with a view to assimilating them. Instead they are told that that the Armenians were fighting alongside the Russians, in the process killing many Muslim Turks. They are also told that the deportations and massacres of 1915 were in response to this treachery, and that diaspora claims that as many as 1.5 million Armenians lost their lives are grossly inflated and motivated mainly by a desire for money and territory.

For the past eighty years, Turkeys powerful army and state bureaucracies have guarded the official history with the greatest zeal. Its penal codes are laden with laws severely curbing free expression, ensuring that most Turks have had little or no access to any information that might challenge or complicate the official line. The break with the past was greatly aided by Ataturks Alphabet Revolution (which moved Turkey from the Arabic to a Latinate script, thereby making it impossible for later generations to read anything published before 1928) and also by the Language Revolution that followed: although reformers did not in the end rid Turkish of all words of Arabic or Persian origin, they did manage to excise almost two-thirds of its vocabulary. Offered a single and unchanging version of the past, Turkeys schoolchildren are to this day encouraged not to dwell on it, and to think instead about the great and prosperous nation that Turkey might one day become if all its patriotic citizens forget their tangled Ottoman roots and work together. But as the Republic travels through its ninth decade, it has found itself under growing pressure to democratise, with many of those most in favour of EU accession arguing that Turkey will only truly prosper if it respects the human rights of all its diverse peoples.

To this end, a loose-knit network of grassroots, legal, and academic groups have been arguing for a new definition of Turkishness. In the place of the word Turk, which has racial overtones, they have proposed the word Trkiyeli, which, because it means person of Turkey, would allow its citizens to express ethnic, cultural and/or religious difference while still asserting their allegiance to the nation. While this remains a controversial proposal, there has in recent years been a real and widespread renewal of interest in the Ottoman past, particularly in the area of family history. But even the most superficial investigation, motivated by nothing more than a simple desire to honour ones ancestors, can lead quickly into areas marked taboo.

There are, by some estimates, as many as two million Turks who have at least one grandparent of Armenian extraction. Fethiye etin is one of them. She was born in the south-eastern province of Elazi, in the town of Maden, which straddles the shores of the Tigris River. In Ottoman times Elazi was one of the empires six Armenian provinces; today it is home to Azeri and Kurdish as well as ethnic Turks. Fethiyes father worked as a manager at the towns copper works; after his early death, she moved with her mother and siblings into the home of her maternal grandparents. It was only many years later, when she was a law student in Ankara, that her beloved grandmother revealed to her that her real name was not Seher but Heranu, that she was Armenian by birth, and that she had been plucked from the death march (grabbed from her mothers arms) by the Turkish gendarme who had gone on to raise her as a Muslim. Her story contradicted everything Fethiye knew about her family, her history, and her country. She had assumed herself to be a Muslim Turk; she now discovered a second legacy that threatened to unravel her received identity forever.

Her great achievement in this memoir, written after more than two decades of reflection, is to have cut right through the bitter politics of genocide recognition and denial to tell the human story: to bear witness. Her aim was to reconcile us with our history; but also to reconcile us with ourselves. She wanted to bear witness, to honour, to grieve for all those who lost their lives, their families, and their homes, and to make common cause with all those who wish to make sure that those dark days never return. She wrote it first and foremost for Turkish readers, challenging the distortions of the official history that they all learned as children, and appealing to their common humanity. In this she was far more successful than she could have dreamed. From the day of publication she received, and still receives, numerous calls from people with similar stories, and also from people who simply express their grief. Since its first publication in Turkey in 2004 it has been reprinted seven times. It has also been translated into French, Italian, Eastern and Western Armenian and will soon be available in other languages, including Greek.