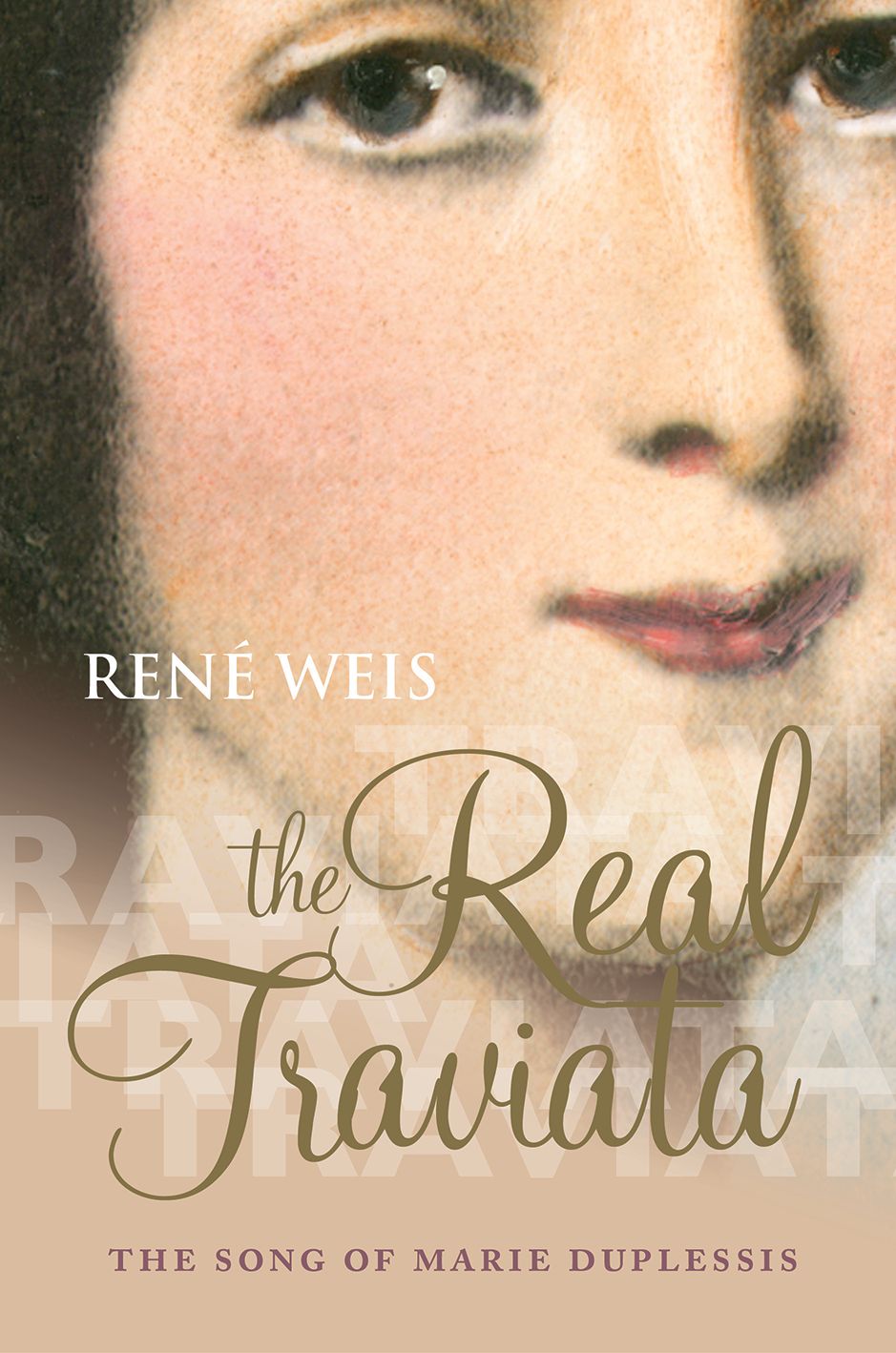

Frontispiece: Unattributed watercolour of Marie Duplessis, perhaps by Charles Chaplin.

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Ren Weis 2015

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015931983

ISBN 9780198708544

ebook ISBN 9780191018169

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith andfor information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materialscontained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For my wife Jean

Preface

The research for this book was carried out in Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and New York City. Much of the story of Marie Duplessis is intimately linked to her home in the Orne, Basse-Normandie, where the horse-pasturing landscapes in which she grew up survive almost untouched. Exploring her native villages of Nonant-le-Pin and Saint-Germain-de-Clairefeuille and the rolling hills between them and nearby Exmes, along with other villages connected to her family, proved illuminating time and again, and often in unexpected ways. It is still possible to walk in the footsteps of the future lady of the camellias in the solitary country lanes that link these Normandy hamlets. They bring to life what must have been the depth of her loneliness as she drifted through them during prolonged spells as a homeless child. I must thank the people in all the villages, particularly in Nonant and Exmes, who were prepared to listen to a stranger and help him with local lore.

I missed Jean-Marie Choulet during my visit to his museum dedicated to Marie Duplessis in Gac but his subsequent correspondence and sharing of his collections artefacts has been most gracious. The mairie of Nonant allowed me to consult their original ancient plans of the village on site as did the departmental archives in Alenon, where I searched extensively for the identity of the villainous Plantier of Exmes. To this day the tourist interested in the story of the girl who became traviata can follow a well signposted track, the Circuit de la Dame aux Camlias, dedicated to various places associated with her.

Inevitably much of the real story now lies hidden in places that are far-flung. Thus poor Maries mothers calvary ended in Clarens near Montreux on Lake Geneva. The Archives Vaudoises of Lausanne and the minuscule local history archive of Montreux were delightfully professional and attractive places in which to work, the latter not much more than a stones throw from the place where the mother of Marie Duplessis has rested since 1830. Cemeteries inevitably played an important role in my researches given the significance of the tomb of the lady of the camellias in Montmartre and the curious fact that in Paris major cemeteries are still guardians of their own records. I am grateful to the staff at the Cimetire de Montmartre for their forbearance and for letting me photograph their documents, which include extensive materials on the lady of the camellias.

Much of the Paris that Marie Duplessis knew, the city of Balzac, Hugo, and Lamartine, survives, including a number of its theatres, buildings, squares, streets, and locations such as Palais-Royal behind the Comdie-Franaise. It was here that Marie Duplessis used to walk and where she first became the plaything of a wealthy man; it was here too that she attended her last show ever. It seems fitting that the small but brilliant archive of the Comdie-Franaise, inside Palais-Royal, should have an important collection bearing on this story, and I am grateful to have been granted access to it and to reproduce two of its images in this book. Two theatres, the Varits and the Gymnase, remain to all intents and purposes the way they were in the 1840s when she was a regular visitor; the Varits in particular is almost untouched as we know from contemporary drawings of it. It is possible today to be seated its orchestra stalls and glance up at the very box where she used to sit. Doing so may not add directly to intellectual knowledge of her but it does feel like touching the face of history.

I am grateful to the Dumas Society for their help with trying to trace extant portraits of Marie Duplessis, to the library of Saint-Germain-en-Laye where Dumas pre et fils spent much time and where La Dame aux Camlias was written, and to the archivists at Versailles, who accommodated my extended visits there. Following her round Europe to, among others, Baden-Baden, Spa, and Bad Ems, meant eavesdropping on seismic changes in European history. Some of the grand buildings of the old German spa resorts still stand, though almost none do now in Spa, one of the last two resorts visited by Marie Duplessis and where I must thank Mr Guy Peeters for his help with the Spa police records. I was well looked after in the tiny local history archive in Baden-Baden and similar courtesies were extended to me in Bad Ems. The Fremdenlisten (lists of foreign visitors) in both, and particularly the Badeblatt, are almost complete and constitute invaluable records for researchers. In 1840s Europe these places rocked to the pulse of polkas, waltzes and power, a far cry from the Sleepy Hollows that they are today, although Baden-Baden can still seduce the modern visitor with its hidden charms.

If Marie Duplessis had wished, she could have allowed herself to be adopted and become the chtelaine of a grand manor house near Doncaster. The extensive papers of Sprotbrough Hall are preserved in the Doncaster Archives and await further exploration, perhaps even with regard to the story of Marie Duplessis.

In Italy I worked in Venice where La traviata first premiered in 1853, particularly in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana and in Casa Goldoni, and in Busseto where the Casa Barezzi, once belonging to Verdis father-in-law, is today fully restored to its nineteenth-century glory. The whole town is redolent with Verdi memories as are his homes in nearby Roncole, where he grew up, and in SantAgata, where he was lord of all he surveyed at the time of La traviata. The guided tours in both places are instructive and revealing, and their atmospheric value, particularly in Roncole and in the church where he played the organ as a child, is hard to overestimate. While much of Verdis