Revolution in Our Lifetime

I t was spring in Harlem, and people were in bloom on the streets. Children playing and beautiful women doing African ballets just by walking down the block. Hustlers and gangsters, challenging the eyes with green and yellow silk suits and red and gold Cadillacs.

I walked down the street with Raymond Masai Hewitt, who was the Panther minister of education in California. He liked walking through the community whenever he visited a local chapter. I had become part of the Panthers National Speakers Bureau. Th e senior leadership had seen me rap at various local fund-raisers for the Panther 21 and decided to make me part of the national speaking team. Masai taught me to walk through the poorest part of town anywhere I was appearing so I could talk about the local problems and issues in my speech. Many colleges and universities border poor communities, and we would try to fire up university students about conditions of poverty and police brutality that existed near their classrooms and dormitories. So in the shadow of Columbia University and the sunrise of the Apollo, Masai and I hung out with Harlem community folk; the grassroots, as Malcolm called them; the lumpen proletariat, as the Panthers called them.

Th ere were two menlumpen brothersfighting on 120th Street. A small crowd was watching. I ran through the crowd and jumped in the middle of the action. Gently, but firmly, I pushed a short dude and a muscle-bound cat apart, without thinking, doing it like I did it all the time. Dont fight, brothers, I shouted. Th ats what the oppressor wants us to dokill each other. Th ose words and my Black Panther buttons were usually enough to cool the situation. If there were no fellow Panthers present to help me, someone from the crowd usually stepped forward to help me keep the combatants apart. Th is time no one moved.

Masai yelled, Jamal, hes got a knife.

I turned to see that Shorty had pulled a hunting knife and was starting to swing at Muscles, the guy I was holding. Swoosh. Th e blade swept by my ear as Shorty tried to leap over me to get his thrust in.

Common sense should have made me jump out of the way and run. But what young Panther has common sense? Instead I walked toward Shorty and his ten-inch blade.

You want to kill somebody, brother? Kill me. Th ats all the pigs want to see is another dead nigga. Any dead nigga will do.

But I aint got no beef with you, Shorty snarled. He sidestepped me so he could lunge at Muscles.

I pushed his knife aside and yelled at Muscles over my shoulder, Split, man. Run! Muscles blended into the crowd and made his retreat. Its over, brother, I yelled at Shorty. Hes gone.

By this time Masai was at my side. Shorty had lowered his knife, but I was still worried that he would run Muscles down and stab him.

Why dont you let me hold the knife?

What? Shorty barked, like I had just asked for a kidney.

You could get it from the Panther office later. Right on 122nd and Seventh Avenue.

I know where the office is, Shorty replied. My aunt got clothes and food there before. Shorty handed me the hunting knife and walked off.

Masai looked at me and shook his head. Are you crazy, Jamal? You dont jump in front of a knife like that. It was a warning and a compliment at the same time.

When I was a kid there was a neighborhood wino who we called Mr. Charlie. Now this was a funny name for a black man, since Charlie and Mr. Charlie were nicknames commonly reserved for white people. But our parents would not let us call any adult by their first name, so Charlie the wino became known to us kids as Mr. Charlie.

Th ere were two cool things about Charlie. One, after he downed about a pint of wine and got his head where he needed it to be, he would forget we were kids and share the second pint with us. Two, he would tell us crazy stories about the Korean War. Mr. Charlie was in a black unit that saw two-thirds of its men killed in combat, and he told us he was shell-shocked and on full disability from the Veterans Administration. It wasnt recognized as posttraumatic stress disorder in those days, but Mr. Charlie had clearly been damaged by the war.

One story he told was about driving in a convoy at high speeds late at night with the headlights off, so Korean artillery could not get a fix on their positions. Every so often a Korean local would run in front of the truck as though he wanted to be killed. Drivers were ordered not to stop for fear of the enemy opening fire, and sometimes these people would get hit and the convoy would roll on. Mr. Charlie explained that Korean men werent actually trying to kill themselves, but instead wanted to kill a demon that was riding on their back. Th ey believed the only way to do this was to have a truck barely miss them, and that would kill the demon.

As I grew into my teenage years, I began to secretly believe that a demon was on my back and that it would take a near brush with death to remove it. Not only did my demon ride me, but I believed he killed many people close to me, like Pa Baltimore; my mother, Gladys; and Panther leaders like Bunchy Carter and John Huggins who were assassinated on my birthday. A part of me believed these deaths were all my fault, as was the arrest of the Panther 21 because of the actions of Yedwa, my mentor. So I kept pushing myself into dangerous situations, hoping that those near-miss razor slashes and gunshots would kill the demon, once and for all.

Th e Panther office was essentially a crisis and relief center with socialist politics. People would come in at all hours to have us break up disputes, intervene when the cops were making arrests, or for emergency medical care and disputes with slumlords. A few people even kicked the heroin habit in the Panther office. We once took turns sitting with a twenty-year-old brother named Stan as for three days he sweated, shivered, cramped, and vomited. He had tried to kick the drug a couple of times before but felt that having the Panthers standing guard over him was the charm he needed to break the habit.

Drugs were an epidemic in Harlem. Th ere were intersections and blocks where junkies would line up to buy drugs in full view of the cops and the community. In fact, many of the cops were on the drug dealers payrolls, and the community felt powerless to do anything. We would claim certain areas as liberated territory and make it plain to the drug dealers that we would deal with them if they came there. Blocks where we organized buildings, breakfast programs, liberation schools, and so on were off limits.

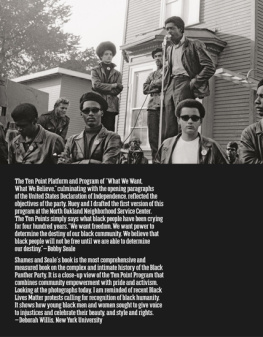

But we knew the Panthers alone could not run all of the drug dealers from the community. It would be the community itself, strong and organized into a peoples party and a peoples army, that would make it impossible for drugs and crime to exist. Our goal was not to have every black person in the community join the Black Panther Party but rather to make the Black Panther Party obsolete because the whole community had become politicized and organized. In our youth, fueled by enthusiasm, we truly believed this would happen. Th e only question was how long it would take.

One night a group of us community activists were hanging out in the dorms of Columbia UniversityPanthers, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Young Lords, Asian activists, and members of the womens movement. We got into a heavy debate about how long the revolution would take. One year, an optimist shouted. Felipe Luciano, Denise Oliver, and Yoruba Guzman from the Lords predicted Puerto Rican independence and socialism within two years. Five years, a pragmatist countered. Finally we agreed that the military- industrial complex of America was too difficult an enemy to overcome quickly and that the revolution would take at least ten years. Th is led us to the horrifying realization that those of us who lived might be near or over thirty when the peoples victory arrived.

Next page