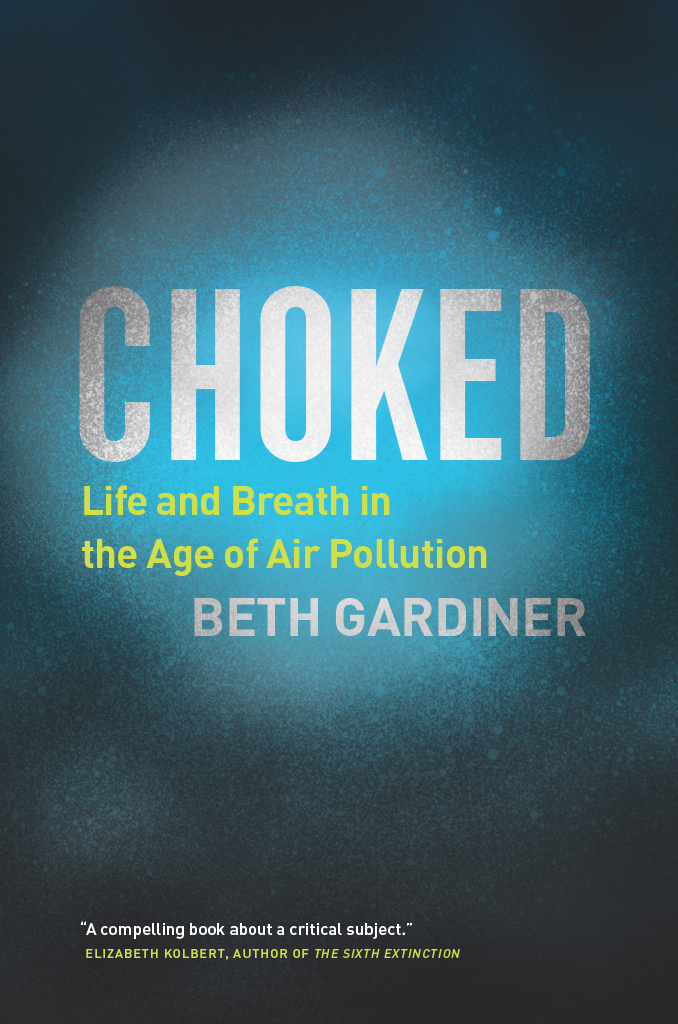

Choked

Choked

Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution

Beth Gardiner

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

2019 by Beth Gardiner

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-49585-9 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-63079-3 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226630793.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gardiner, Beth, author.

Title: Choked: life and breath in the age of air pollution / Beth Gardiner.

Description: Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018052335 | ISBN 9780226495859 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226630793 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH : AirPollution. | AirPollutionSocial aspects. | AirPollutionHealth aspects. | Environmental quality.

Classification: LCC TD 883.1 . G 37 2019 | DDC 615.9/02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018052335

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Dan and Anna

Contents

Inhale

The Meaning of a Breath

A human breath begins in the deepest reaches of the brain, wherefar beneath consciousnessthe bodys most basic and essential functions are regulated. Just above the point where the spine meets the skull, tiny receptors detect rising levels of carbon dioxide, then stimulate nearby clumps of neurons. Between 12 and 20 times a minute, perhaps 20,000 times a day, millions of times a year, over and over and over again from the first cry of birth until the very last moment of life, those neurons fire signals ordering the muscles of the diaphragm and rib cage to contract.

Message received, the dome-shaped diaphragm flattens, and the ribs move upward and out. As the chest cavity expands, the pressure within drops, drawing air through the nose and mouth. Down the back of the throat, over the voice box, it follows its path deeper and deeper into the body.

To the naked eye, the lungs are unremarkable hunks of spongy pink tissue. Only when they inflate, puffing up like balloons, but faster and more dramatically, does their uniqueness become apparent. In the stylized illustrations of medical textbooks, a lung looks like an upside-down tree, a symmetrical maze whose branches get smaller and smaller as they divide into more than a million tiny twigs.

Its up close that the structures elegant intricacy comes into focus. Hunched over his microscope, the seventeenth-century Italian anatomist Marcello Malpighi was the first to get a glimpse. Until then, the best medical minds believed air mixed directly with blood inside the lung. What Malpighi discovered is now a biological commonplace, taught to middle schoolers: Inhaled air fills sacs that cluster at the airways ends like miniature bunches of grapes. There are some 300 million of these alveoli in a pair of lungs, and their surface area is often likened, in total, to the size of a tennis court. Separated from them by membranes one one-hundredth as thick as a hair, tiny capillaries carry blood low in oxygen and laden with carbon dioxide. The gases rush across the barrier, and oxygen molecules bind to hemoglobin, then whoosh toward the heart, ready to be delivered wherever they are needed.

Like so much about the body, a breath is at once astonishingly simple and magnificently complex, delicately balanced yet highly resilient. Unlike other essential functions, the beating of the heart or the peristalsis of digestion, breath can also be controlled by the conscious mind, when we laugh or speak or hold it in to dive underwater.

The lung, too, is a point of vulnerability. While it has its defensesthe mucus that traps some contaminants, the hairlike cilia that sweep away othersthis is the place where the outside world makes its way into the very center of the body, barriers left far behind as the air and whatever it carries come within a whisper of the bloodstream.

Lacking microscopes and an understanding of airs composition, the ancients struggled to grasp the hows and whys of a function they could plainly see was essential. Aristotle, a physicians son, believed breathing released heat generated by the vital fires of the soul. It would take millennia to definitively correct such misconceptions, but there was one fact the philosopher and his contemporaries understood well: Our very existence depends upon air. The last act when life comes to a close is the letting out of the breath, wrote Aristotle. And hence, its admission must have been the beginning.

* * *

I didnt think much about the meaning or mechanics of breath when I was growing up. Until I was five, I lived in Fort Lee, New Jersey, in an apartment building overlooking the entrance to the George Washington Bridge. It was, and still is, a notorious traffic choke point, where the New Jersey Turnpike and a tangle of other highways merge into one. Suburbanites commuting to offices in New York sit bumper to bumper with trucks rolling north along the I-95 East Coast corridor, waiting to cross into the city. This was the early 1970s, the dawn of environmental consciousness, a time when American cars were exponentially dirtier than today, their fuel tainted with lead, sulfur, and other dangerous toxins. Along with my peersthe Jennifers, Davids, and Lisas who lived in the building tooI breathed it all in as we ran and jumped in the concrete playground out back.

Years later, in my twenties, I watched crosstown buses lurch by a few stories below my Manhattan apartment, heading into and out of Central Park. When I cleaned, the soot that coated the windowsill blackened big wads of paper towels. It took several goings-over, and a lot of soapy spray, to get the paint on the sill white again.

At 30, I moved to London with the charming Brit whod stolen my heart. For 18 years, more than half of them with our chatty, energetic daughter, weve breathed the diesel fumes that foul the citys air. Londons pollution is just one piece of a health disaster playing out across Europe, belying the continents reputation for environmental progressivism. I can smell the exhaust when Im out running errands, meeting a friend for coffee, or walking Anna to school, clouds of it billowing into our faces. After a few minutes on a busy road, I often have a mild headache.

For a long time, I saw that awful air as just an annoyance. But as Ive come to understand pollutions profound effects on the human body, its grown into something more: the focus of nagging worry, a fear for my daughters well-being, and my own.

I try my best to protect her, of course. But I cant change the air that surrounds us, nor wish away our citys diesel mess. So I find myself veering from anxiety to anger. Landing sometimes, too, at a willful blocking out of the danger, as a parents urge to shield a vulnerable child tugs against the reality of an individuals powerlessness in the face of larger forces. Its that back-and-forth pull of emotions that set me on the path to writing this book.

What Ive found since is that the taint my family and I breathe is only one strand of a far bigger story. Around the world, from Fort Lee Nothing is as elemental, as essential to human life, as the air we breathe. Yet around the world, in rich countries and poor ones, it is quietly poisoning us.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).