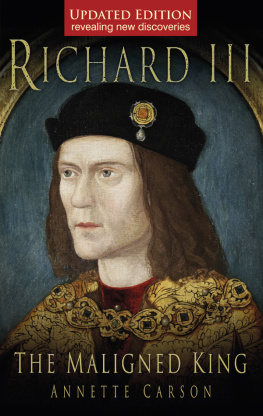

RICHARD III

THE MALIGNED KING

In memory of Isolde Wigram,

gallant co-founder of the present day Richard III Society,

and champion of the standpoint that the princes in the Tower were not murdered there, nor killed by Richard III.

The purpose and indeed the strength of the Richard III Society derives from the belief that the truth is more powerful than lies a faith that even after all these centuries the truth is important. It is proof of our sense of civilised values that something as esoteric and as fragile as a reputation is worth campaigning for.

HRH The Duke of Gloucester, KG, GCVO, Patron

RICHARD III

THE MALIGNED KING

ANNETTE CARSON

Also by Annette Carson:

Flight Unlimited (with Eric Mller)

Flight Unlimited 95 (with Eric Mller)

Flight Fantastic: The Illustrated History of Aerobatics

Jeff Beck: Crazy Fingers

Richard III: A Small Guide to the Great Debate

Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project (with J. Ashdown-Hill, D. Johnson, W. Johnson and Philippa Langley)

Richard Duke of Gloucester as Lord Protector and High Constable of England

First published in 2008

This edition first published in 2013

Reprinted 2014, 2015

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

Annette Carson, 2008, 2009, 2013, 2017

The right of Annette Carson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7314 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

Text illustrations

Cover illustration

Probably the earliest surviving version (c. 1510) of a portrait from life. Distortions were added to all known portraits, including the grimly clenched mouth overpainted on this before restoration in 2007. (Society of Antiquaries of London ref. LDSAL 321)

All images not otherwise attributed are Geoffrey Wheeler, whose invaluable picture research is gratefully acknowledged.

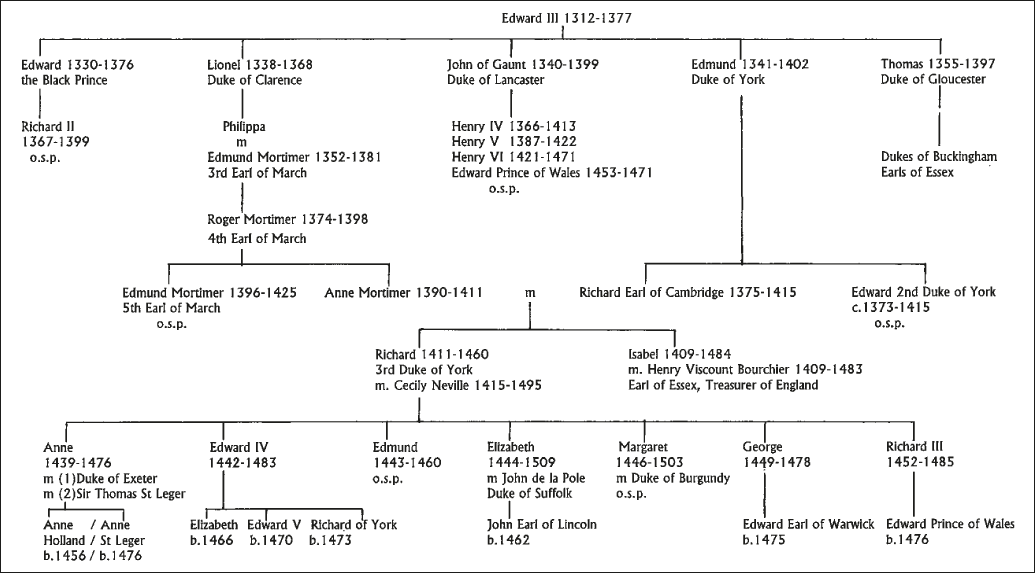

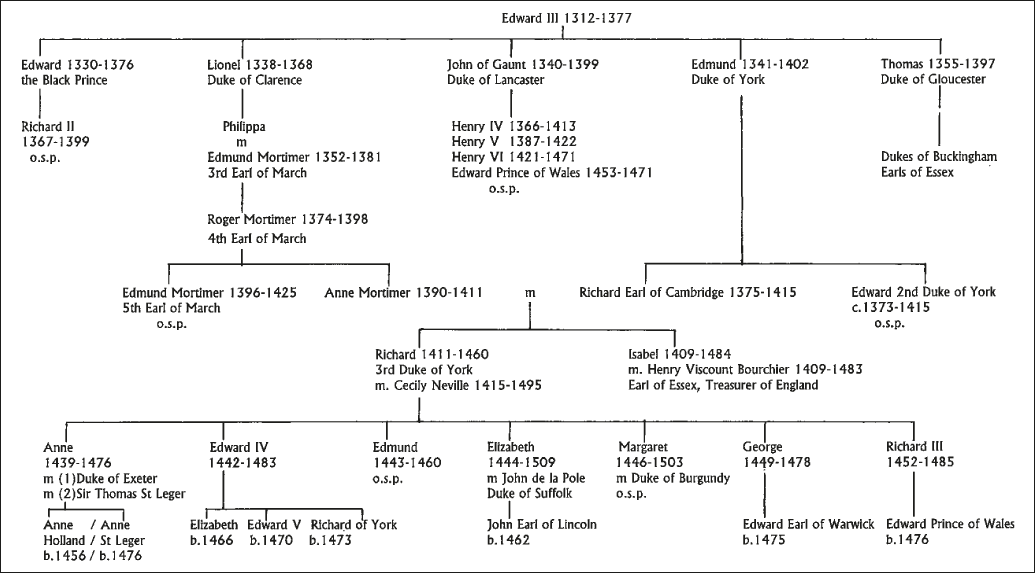

Table 1: Royal Houses of York and Lancaster (simplified)

Preface

This book is not a biography of Richard III. It is a highly personal analysis of the more controversial events of that kings reign, starting with the death of his predecessor and brother, Edward IV, in 1483.

At the outset my aim was to research, not to vindicate. However, in the course of my progress many surprising things became evident. Among them was the determination of most historians to place negative interpretations on Richards actions, while applauding the career of deceit and underhandedness that characterized his nemesis, Henry VII.

Thus, the thrust of my writing gravitated towards Richards defence. I do not claim to have found unequivocal answers; but I have delved as deeply as possible into particular topics that seem to need exposure to the clear light of day, seeking for a kernel of truth under layers of misinformation. Sometimes I offer conjectures, mine and other peoples, that disturb long-established comfort zones. I offer them in support of a truth too often overlooked: we do not know as much as we are led to think we know.

Although my main interests lie in the oft-ignored nooks and crannies of history, let me emphasize that this book is written for the ordinary reader anyone who knows a little about King Richard III of England and would like to know more. A strand of narrative runs through it all which ensures that we keep following the story of Richard IIIs reign as it unfolds.

Above all you will find none of the sweeping judgements so loved by historians (good, evil, prudent, ambitious, pious, hypocritical, etc.). Richard was a man of his times and a king of his times, concerned with matters beyond the experience of any twenty-first century commentator.

Current academic orthodoxy concedes that Richard III was probably not the monster of Tudor mythology, but assumes the rationale behind his seizure of the crown was a fiction; that being a usurper, he must have had his two nephews murdered because that was what usurpers did; and that their murder was, on balance, confirmed by the bones inurned in Westminster Abbey by Charles II. These are, inter alia, assumptions that I challenge in these pages.

Those who cast Richard III as an unprincipled usurper have done so because they have made judgements and drawn conclusions: no concrete evidence exists to convict him. But academic orthodoxy is a tough nut to crack, and is passed on to each new generation of scholars.

If Richard III is to be assessed, let it be on his overall conduct as a sovereign. When it comes to matters in which he had some control, such as legislation brought before Parliament, his record has been recognized over the centuries as significant and enlightened. By contrast with kings before and after him, he indulged in no financial extortion, no religious persecution, no violation of sanctuary, no burning at the stake, no killing of women, no torture or starvation and no cynical breach of promise, pardon or safe-conduct in order to entrap a subject. Anyone who has been led to believe that Sir Henry Wyatt was tortured by Richard III is recommended to read my comprehensive refutation of that myth.

After Richards death the story of the murderous, tyrannical king was fostered by his killers and became part of English legend. Encouraged by a climate of Court approval, chroniclers vied with each other to heap venom on his memory and devise horror stories to add to his constantly growing list of crimes. In their ignorance they jeered at his physical form and heaped on him an assortment of grotesqueries, believing that an ill-formed body was the outward manifestation of an evil mind. This fictitious Richard III became the subject of one of Shakespeares most alluring melodramas. Shakespeare had little need for invention: he found the entire artifice already crafted to perfection by the Tudor chroniclers.

By contrast, the scant information dating from pre-Tudor times is generally found in letters and jottings, cursory government records, or a few isolated narratives. The unreliability of the latter is amply demonstrated in the works of John Rous, a Warwickshire priest who fancied himself a chronicler. Rous generously left to posterity two opposite views of Richard III: the first, composed during his reign, admiring and complimentary; the second, composed after his downfall, hostile and vituperative.

The example of Rous illustrates how important is familiarity with the source material when it comes to forming an independent opinion. Here, therefore, you will find an unusual approach: an Appendix is provided which contains a list of the principal sources used, together with notes about factors which may be relevant to the credibility of the writers. These include dates; partisanship; motivation; whether answerable to a patron; whether facts were accessed at first hand and, if at second hand, the reliability of the likely informants. The notes are mine, based on analyses by historians and academics.

Next page