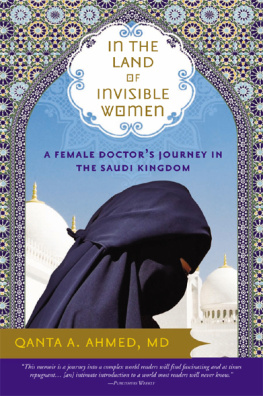

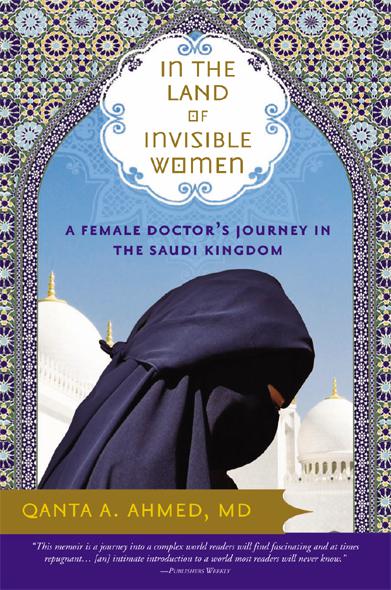

2008 by Qanta Ahmed

Cover and internal design 2008 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover photos iStockphoto.com/Naci Yavus, iStockphoto.com/Klass Linbeek-van

Kranen

Cover Design by Kirk DouPonce, Dog Eared Design, LLC.

Author Photo Jack Alterman

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This book is a memoir. It reflects the author's present recollections of her experiences over a period of years. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ahmed, Qanta.

In the land of invisible women : a female doctor's journey in the Saudi Kingdom / Qanta A. Ahmed.

p. cm. ISBN-13:978-1-4022-2002-9

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Ahmed, Qanta. 2. Women physiciansIslamic countriesBiography. 3. Women in medicineIslamic countriesBiography. 4. Muslim physiciansIslamic countries Biography. I. Title.

R692.A346 2008

610.82092dc22

[B]

2008009548

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents, who gave me my Islam and my love of words.

And for Joan Kirschenbaum Cohn, who shows me how to live,

as a better woman, as a better Muslim.

CONTENTS

THE BEDOUIN BEDSIDE

S EEKING RESPITE FROM THE INTENSITY of medicine, I trained my eye on the world without. Already, the midmorning heat rippled with fury, as sprinklers scattered wet jewels onto sunburned grass. Fluttering petals waved in the Shamaal wind, strongest this time of day.

In a pool of shade cast by a hedge, a laborer sought shelter from the sun. An awkward bundle of desiccated limbs, the Bengali lunched from a tiffin. His shemagh cloth was piled into a sodden turban, meager relief from the high heat. Beyond, a hundred-thousand-dollar Benz growled, tearing up a dust storm in its steely wake. Behind my mask, I smiled at my reflection. Suspended between plate glass, a woman in a white coat gazed back. Externally, I was unchanged from the doctor I had been in New York City, yet now everything was different.

I returned to Khalaa al-Otaibi, my first patient in the Kingdom. She was a Bedouin Saudi well into her seventies, though no one could be sure of her age (female births were not certified in Saudi Arabia when she had been born). She was on a respirator for a pneumonia which had been slow to resolve. Comatose, she was oblivious to my studying gaze. A colleague prepared her for the placement of a central line (a major intravenous line into a deep vein).

Her torso was uncovered in preparation. Another physician sterilized the berry-brown skin with swathes of iodine. A mundane procedure I had performed countless times, in Saudi Arabia it made for a startling scene. I looked up from the sterilized field which was quickly submerging the Bedouin body under a disposable sea of blue. Her face remained enshrouded in a black scarf, as if she was out in a market scurrying through a crowd of loitering men. I was astounded.

The scraggy veil concealed her every feature. From the midst of a black nylon well sinking into an edentulous mouth, plastic tubes snaked up and away from her purdah (the Islamic custom of concealing female beauty). One tube connected her ventilator securely into her lungs, and the other delivered feed to her belly. Now and again, the veil-and-tubing ensemble shuddered, sometimes with a sigh, sometimes with a cough. Each rasp reminded me that underneath this mask was a critically ill patient. Through the black nylon I could just discern protective eye patches placed over her closed eyelids. Gently, the nurse lifted the corner of the veil to allow the physician to finish cleansing. In my fascination, I had forgotten all about the procedure.

From the depths of this black nylon limpness, a larger corrugated plastic tube emerged, the main ventilator circuit. It snaked her breaths away, swishing, swinging, with each machine-made respiration. Without a face at the end of the airway, the tubing disappeared into a void, as though ventilating a veil and not a woman. Even when critically ill, I learned, hiding her face was of paramount importance. I watched, entranced at the clash of technology and religion, my religion, some version of my religion. I heard an agitated rustling from close by.

Behind the curtain, a family member hovered, the dutiful son. Intermittently, he peered in at us. He was obviously worrying, I decided, as I watched his slim brown fingers rapidly manipulating a rosary. He was probably concerned about the insertion of the central line, I thought, just like any other caring relative.

Every now and again, he burst into vigorous rapid Arabic, instructing the nurse. I wondered what he was asking about. Everything was going smoothly; in fact, soon the jugular would be cannulated. We were almost finished. What could be troubling him?

Through my dullness, eventually, I noticed a clue. Each time the physician's sleeve touched the patient's veil, and the veil slipped, the son burst out in a flurry of anxiety. Perhaps all of nineteen, the son was demanding the nurse cover the patient's face, all the while painfully averting his uninitiated gaze away from his mother's fully exposed torso, revealing possibly the first breasts he may have seen.

Each staccato command was accompanied by the soggy mumblings of Arabic emerging from behind the physician's mask, asking the nurse to follow suit and fix the veil. The physician sounded unconcerned, yet the son was suspended in an agonizing web of discomfort. He paced in anxiety about his mother's health, anxiety about her dignity, and anxiety about her responsibilities to God. The critically ill, veiled face and her bared breasts, pendulous with age, posed an incredible sight. I was as bewildered as the Saudi son.

I gazed at the patient, completely exposed, except for her veiled face, and her fragile son supervising (why not a daughter, I thought). The veiling, even when her face slept, deeply comatose from sedation, was disturbing. Surely God would not require such extreme lengths to conceal her features from her doctors who needed to inspect her body? Did an unconscious sickly Muslim have the same responsibilities as a conscious, able-bodied one? Although a Muslim woman myself, I had never faced such questions before. My debate was internal and solitary; those around me were quite clear of their obligations. The patient was a woman and needed to be veiled. The physician was instructing the Filipina nurse throughout to comply with the son's concerns. The Filipina was obviously inured to the whole spectacle. The son knew his duties to his mother. Only I remained locked in confusion.