Copyright 2012 by Ty Burr

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burr, Ty.

Gods like us : on movie stardom and modern fame / Ty Burr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90742-4

1. Celebrities in mass mediaHistory20th century. 2. Celebrities in mass mediaHistory21st century. 3. FameSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. FameSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory21st century. 5. Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory21st century. I. Title.

P 96. C 35 B 85 2012 306.48dc23 2012000618

www.pantheonbooks.com

All photographs are courtesy of the Kobal Collection/Art Resource, New York.

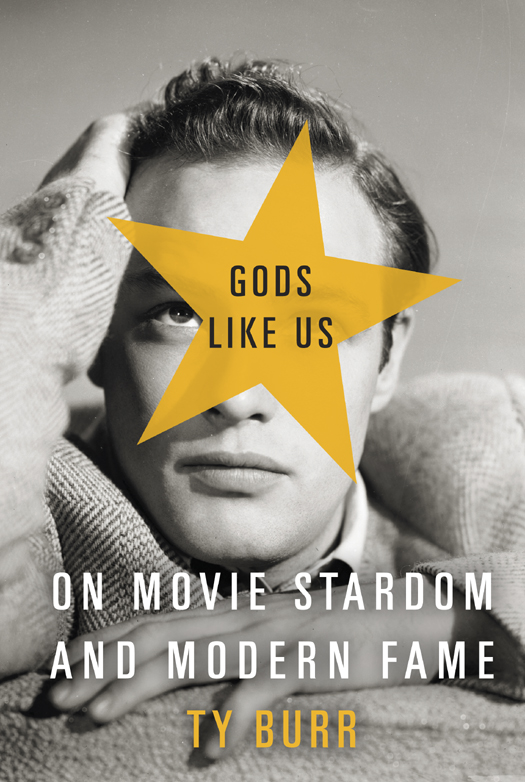

Jacket photograph of Marlon Brando by John Kobal Foundation/Getty Images Jacket design by Emily Mahon

v3.1

For Lori

Its allnothing! Its all a joke. It can all be explained, I tell you. Its allnothing.

CHARLIE CHAPLIN, under assault from a mob of fans outside the Cirque Medrano, Paris, 1925

Contents

Introduction: The Faces in the Mirror

W hat are the stars really like?

That question is not the subject of this book. The subject of this book is why we ask the question in the first place.

Still, people want to know. In my day job, Im a professional film critic for a major metropolitan daily newspaper and throughout the 1990s I wrote reviews and articles for a national weekly entertainment magazine. Over the years, Ive interviewed a number of actors and directors, ingnues and legends, and often the first question Im asked by people is just that: What are they really like?

The answers always disappoint. Always. They range from Pretty much what you see on the screen to Not all that interesting sometimes to Pleasantly professional to an unspoken Why do you care? When pressed (and Im usually pressed), Ill allow that Keira Knightley and I had a lovely chat once and Lauren Bacall was nastier than she needed to be to a young reporter just starting out. That Laura Linney seemed graciously guarded, Steve Carell centered and sincere, Kevin Spacey cagey and smart. I once took the young Elijah Wood to a Hollywood burger joint while interviewing him for the magazine. He was a kid who really liked that burger, no more and no less.

They are, in short, working actors, life-sized and fallible. There is no mystery here. But this is not what you want to hear, is it? If theres nothing genuinely special about movie stars, why do we give them our money? Why do we pay for cheaper and cheaper substitutesreality stars, hotel heiresses, the Kardashians? Are we interested in the actual person behind the star facade, or just desperate to believe the magic has a basis in reality?

In truth, the relationship between persona and person can be problematic. Of all the celebrity encounters Ive experienced, the one that sticks with me is the briefest, most random, possibly the saddest. Early one morning, many years ago, I came out of my apartment building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and got ready to go for a run. As I breathed the spring air, the door to the adjoining building opened and another jogger emerged. We started stretching our hamstrings side by side, and I glanced over and acknowledged the other man with a friendly nod.

Three almost invisible things happened in rapid succession. First, he nodded back with a pleasant smile. Second, I realized that he was Robin Williams. Third, he realized that I realized he was Robin Williams, and his eyes went dead. Not just dead: empty. It was as if the storefront to his face had been shuttered, cutting off any possibility of interaction. There wasnt anything rude about this, and I respected his privacy, honoring the code observed by all New Yorkers who know they can potentially cross paths with an A-list name at any corner deli. Or was it his celebrity I was respecting? Whichever, a very small moment of human connection between two people had been squelched by the appearance of a third, not-quite-real person: the movie star. The second I recognized who the other jogger was, his persona got in the way. I couldnt not see him as Robin Williams. And he knew it.

This happens dozens of times in any well-known persons day. Its why Williamss eyes shut down so completely; its why I left him alone and went for my run. I felt bad for the man, even if I hadnt actually done anything. Because people do, in fact, do things. Think of all those fans who meet movie stars and insist on being photographed with them, the snapshot serving as both proof and relic. Think, too, of the man who shot and killed John Lennon but made sure to get his autograph first.

Why a history of movie stardom? To celebrate, interrogate, and marvel over where weve been, and to weigh where we are now. As the twenty-first century settles into its second decade, we are more than ever a culture that worships images and shrinks from realities. Once those images were graven; now they are projected, broadcast, podcast, blogged, and streamed. There is not a public space that doesnt have a screen to distract us from our lives, nor is there a corner of our private existence that doesnt offer an interface, wireless or not, with the Omniverse, that roiling sea of infotainment we jack into from multiple access points a hundred times a day. The Omniverse isnt real, but its never turned off. You cant touch it, but you cant escape from it. And its most common unit of exchange, the thing that attracts so many people in the hopes of becoming it, is celebrity. Famous people. Stars.

Or what weve traditionally called stars, which traditionally arose from a place called the movies. As originally conceived during the heyday of the Hollywood studio system, movie stars were bigger and more beautiful than they are now, domestic gods who looked like us but with our imperfections removed (or, in some cases, gorgeously heightened). Our feelings about them were mixed. We wanted to be these people, and we were jealous of them too. We paid to see them in the stories the movie factories packaged for us, but we were just as fascinatedmore fascinated, reallywith the stories we believed happened offscreen, to the people the stars seemed to be.

Not many of us remember those days. Moreover, few are interested in connecting the dots between what we want from movie stars now and what we wanted from them thenand the then before that, and the then before that, all the way back to the first flickering images in Thomas Edisons laboratory. The desires have changed, but so has the intensity. Mass media fame, a cultural concept that arose a century ago as a side effect of a new technology called moving pictures, now not only drives the popular culture of America (and, by extension, much of the world), but has become for many people a central goal and measure of self-worth.

When we were content to gaze up at movie stars on a screen that seemed bigger than life, the exchange was fairly simple. We paid money to watch our daily dilemmas acted out on a dreamlike stage, with ourselves recast as people who were prettier, smarter, tougher, or just not as scared. The stories illustrated the dangers of ambition, the ecstasies of falling in love, the sheer delight of song and dance. Because certain people embodied uniquely charismatic variations on how to react in certain situationsBogarts street smarts, Kate Hepburns gumption, Jimmy Stewarts bruised decency, Bette Daviss refusal ever to budgewe wanted to see them over and over again.