Table of Contents

For my parents,

James Ichiro and Teruko Furiya

Swallowing Fish Bones

My mother first told me this story when I was six years old, before I knew that the language she spoke was Japanese.

Her personal tale takes place in Tokyo during the 1930s, when she was a young girl. Her neighborhood, she explained, was a jigsaw puzzle of low-story, fragile houses constructed of wood and paper. The homes survived the many earthquakes that shook Japan, yet most burned away like dried leaves when Tokyo was bombed during World War II.

Every day a community of mothers in the neighborhood gathered together to feed their babies a midday meal and to rest from endless household duties and the tongues and ears of nosy in-laws.

While the older women gossiped and watched over the little ones, the younger women made lunch for the babies, who ate softer versions of what their mothers served at their tablesrice, fish, soup, and vegetables.

Often the fishmongers wife brought a whole fish to broil until the skin charred and cracked on a small outside grill. The mothers slid the flaky, sweet, white meat off the bone with the tap of a chopstick.

Using their fingers to feel for any stray fish bones, they thoroughly mashed, pinched, and poked the tender fish meat before mixing it with rice and moistening it with dashi (fish stock). Despite all the care, sometimes a transparent bone, pliable and sharp as a sharks tooth, slipped past scrutiny.

I picture her wearing braids and standing in the distance, quietly observing yet part of the gathering. Now her short hair frames her face like the black slashes of an ink brush. In this story my mother explains how before modern medicine, the mortality rate was high not only for newborns, but even for healthy men, who were struck dead from illnesses that would start as a common cold.

One day you are in good health, the next... Moms eyes flicker at this point, like two flints sparking. She snaps her fingers at the swiftness of it all. Back then, mothers needed reassurance that their babies were strong, and eating was an infants first test of survival. If the baby didnt know how to eat, suck from its mothers nipple, or push out a fish bone, the child wouldnt know how to survive when she grew older.

One day during a feeding, my mothers story goes, the wagashi- ( Japanese pastry) makers baby sat still and silent, holding his mouthful of fish and rice.

Eh? grunted Obasan, the old matriarch of the group, as she peered at the baby through thick spectacles.

The wagashi-makers wife nervously patted the baby on the back as all the other mothers talked quietly, trying not to stare. Strings of saliva and bits of fish dribbled out of his mouth. His tiny bud of a tongue moved in and out before finally pushing out a small fish bone, the size of a pine needle.

The wagashi-makers wife gushed with pride at her babys grit for life. Obasan cackled loudly, proclaiming he would live a strong, healthy life, as the other women sighed and laughed with relief. Years later, Mom says, he became a doctor and people credited his success to overcoming the fish bone.

Another time the soba noodlemakers baby swallowed a small bone. Reminiscent of the first infant, he sat still and silent, but no spittle and bone came out. Instead, he swallowed. Not long after, the baby developed a fever and refused to take his mothers milk. A doctor removed a small bone that had been lodged in his throat, and the soba-makers wife began worrying about her babys future. No one was surprised when he died of tuberculosis at the age of ten.

Unlike stories with resolution that I would become accustomed to hearing from teachers and other adults throughout my youth, Mom left the tale at that, leaving me baffled as to its lesson or moral. Growing up, whenever I complained about mistreatment by a friend or the unfairness of some school interaction, my mother repeated her story of the infants and the fish bones. Growing up in the only Japanese family in Versailles, Indiana, I quickly learned that I would have to overcome many fish bones. My very first notion of how different we really were struck me among the pastel-colored molded trays and long bleached wood tables of the school cafeteria.

My elementary school lunchroom was a sweaty, brightly lit place that reeked of hot cooking oil, Pine-Sol, and the yeast from rising bread dough. It was dead quiet when empty, and otherwise it echoed with the sound of childrens high-pitched talk and laughter and heavy wood and metal chairs scraping against the tile floor.

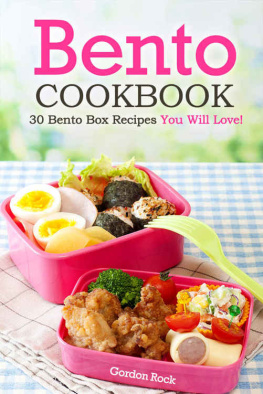

I had never eaten a lunch before then without my parents. My two older brothers, Keven and Alvin, ate lunch at school. Mom was a stay-at-home mother. She churned out three meals a day as efficiently as a military mess hall. My father worked second shift at a factory in Columbus, Indiana, where he assembled truck engines. Because he started his shift midafternoon, he ate a hot, filling lunch at home to compensate for his dinner, a cold bento box of rice, meat, and vegetables, with a cup of green tea from his thermos.

These lunches with my parents were magnificent feasts made in our tiny kitchen. The size of a hall closet, the small room became alive during lunchtime, like a living, breathing creature, with steam puffing from the electric rice cooker, rattling from the simmering pots, and short clipping notes of Mom chopping with her steady hand guiding her nakiri bocho ( Japanese vegetable knife).

At the dining room table, Dad and I grazed on cold Japanese appetizersspicy wilted cabbage pickled in brine with lemon peel, garlic, smashed whole red chili peppers, and kombu (seaweed). Meanwhile, Mom prepared hot dishescubes of tofu garnished with ginger and bonito flakes (dried fish shavings). There was salmon fillet, if we could get it, grilled to the color of Turkish apricots on a Japanese wire stove-top contraption; or sirloin, sliced tissue-thin, sauted with onions, soy sauce, and a dash of rice wine. And there was always a bowl of clear fish broth or cloudy miso soup and steamed white rice.

As I was used to such sumptuous lunches, it wasnt long before the novelty of my schools cafeteria fare wore off and my eyes wandered toward the lunch boxes other children brought from home. From inside the metal containers, they pulled out sandwiches with the crusts cut off, followed by tins of chocolate pudding and homemade cookies.

My best friend, Tracy Martin, was part of the lunch box brigade. Her mother packed the same lunch items every daya cold hot dog and applesauce. We also ate with Mary, a Coppertoned, baby-faced girl with a Clara Bow haircut, whose mother precut all the food in her lunch box, even her cookies, into bite-size pieces.

I wanted to be a part of this exclusive group, and after much pestering, I was thrilled when my mother relented and agreed to pack my lunches.