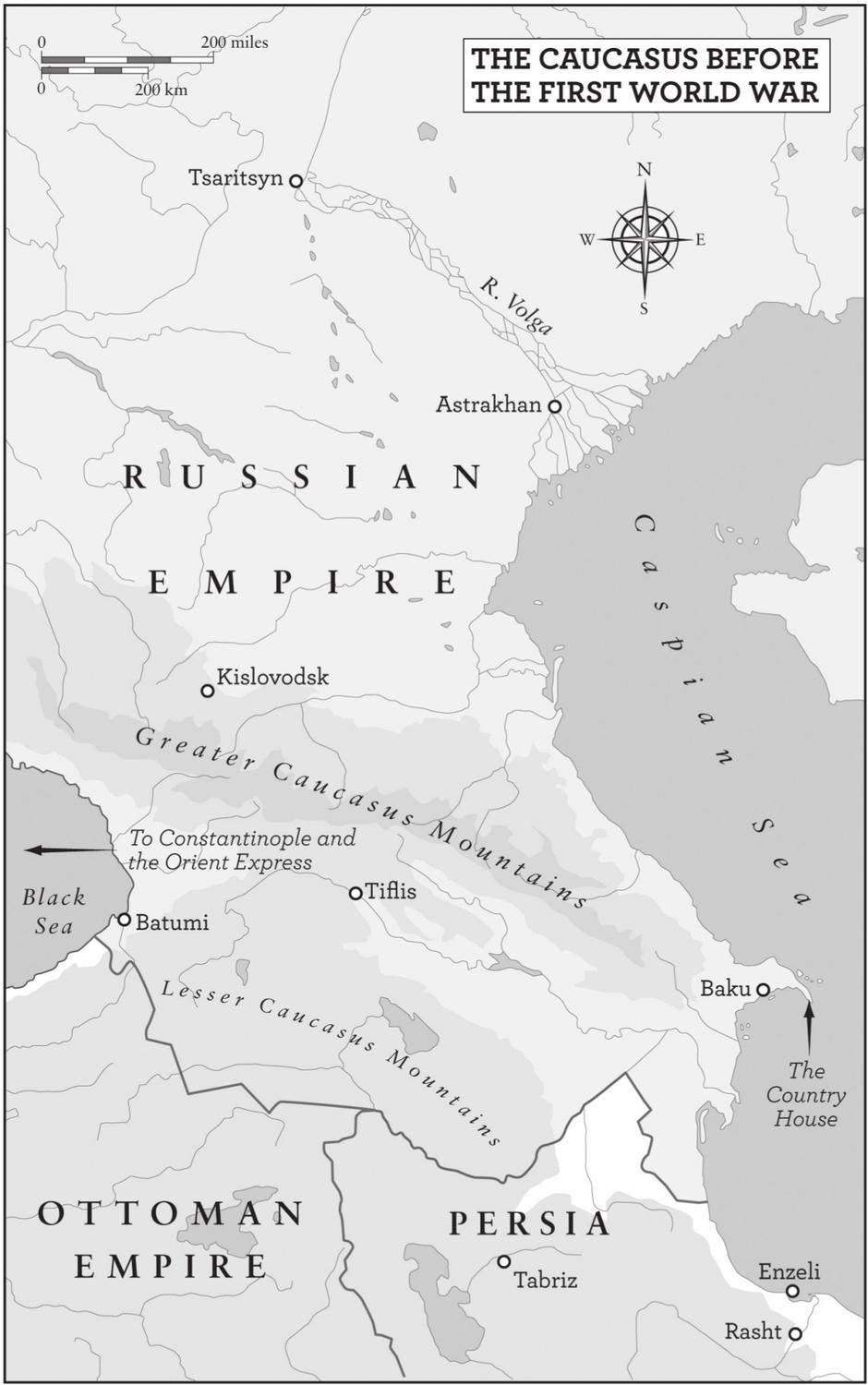

T he Caucasusa range of majestic mountains and gentler foothills where Europe meets Asia. The Black Sea laps at the western edge, the Caspian at the east. This natural barrier separates Russia from Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia and, farther south, Iran and Turkey. It was in the Azerbaijani city of Baku that the author of Days in the Caucasus, Banine, was born in 1905.

Ummulbanu Asadullayeva, to give Banine her full name, was the granddaughter of peasants who had become fabulously wealthy through oil. Her maternal grandfather, Musa Naghiyev, struck oil on his patch of land and became one of the richest men in the Russian Empire, while her paternal grandfather, Shamsi Asadullayev, built a flourishing oil business through shrewd investment.

Oil had turned Banines Baku from a sleepy port on the Caspian Sea into a bustling, booming city, bursting with ideas. This was an era of enlightenment, of social and political ferment, of growing self-awareness for the Muslim Azerbaijani population and for all workers, regardless of ethnicity. Education made huge stridesin 1901 the first secular school for Muslim girls opened in Baku, where Banine was so unhappy she cried every day for two months. Newspapers were published in Azerbaijani Turkish. The first opera in the Muslim world, a fusion of traditional mugham and European operatic style, was performed in Baku in 1908.

This was an era too of unrest and upheaval. The tsar was deposed and the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917. A year later the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was proclaimed, with universal suffrage, including for women, enshrined in its constitution. The Democratic Republic, in which Banines father was a government minister, was to be short-lived, however. She describes the arrival of Russian Bolshevik troops in Baku in 1920: In a matter of moments, without a shot being fired, the Azerbaijani army had melted away. The Republic was dead and victorious Russia was reclaiming its subjects. With my own eyes I had seen the end of a world.

Pogroms, revolutions and the end of empire are the backdrop to Banines coming-of-age tale. She dreams of romantic love and burns with idealism, even sporting a badge of Lenin. Banine escapes into the realm of the imagination and these escapes are mirrored in real life when she flees to Persia, Tiflis, Constantinople, Paris.

In Paris Banine worked as a model for several years, before becoming a writer. Her first book, a novel titled Nami, was published in 1942. But it was her second book, Jours caucasiens or Days in the Caucasus, that received critical acclaim. Published in the French capital in 1945, the memoir established Banine in literary and migr circles. I started to leaf through the book and was soon engrossed, the Russian migr author Teffi wrote in a review in the journal Nouvelles russes. So vividly and wittily does the author reveal to us an utterly unfamiliar world.

Banine wrote a sequel to Days in the Caucasus, Days in Paris, published in 1947. The most successful of her later works was an account of her conversion to Christianity, I Chose Opium. She translated widely into French, including works by Dostoevsky, Tatyana Tolstaya and the German author Ernst Jnger, who became a good friend.

Banine died in Paris in 1992 at the age of eighty-six.

She came to public attention in her homeland only in the late 1980s, when the Soviet newspaper Literaturnaya gazeta published an article about her friendship and correspondence with the Nobel Prize-winning Russian author Ivan Bunin. I first heard of Banine in 2000 when I lived in Baku and wondered about the fate of the oil barons who had left behind such remarkable buildings. Hamlet Qocas Azerbaijani translation of Days in the Caucasus was published in Baku in 2006, and was itself translated into Russian by Gulshan Tofiq Qizi. A translation from the original French into Russian by Ulviyya Akhundova came out in Baku in 2016.

Reading Banines gripping memoir, I was struck by similarities between Baku in the early twentieth century and the city in the early twenty-first. The excitement of the first years of the independent Azerbaijan Republic after the collapse of the Soviet Union mirrored the heady days of the Democratic Republic created in 1918 after the collapse of the Russian Empire. Though the highest hopes have yet to be fulfilled, the Azerbaijan Republic marks its twenty-eighth birthday in 2019.

The cultural tensions so vividly illustrated by Banine continue in Baku to this day, contributing to the citys energy and verve. Russian language and culture still thrive in the capital, alongside the much more widespread Azerbaijani culture. Religion is regaining ground, though in the early twenty-first century it is more often the young who turn to Islam, their grandparents having grown up under the anti-religious Soviet system. Churches too are growing, and services are held in the Lutheran Church, whose Frauenverein (Womens Union) the young Banine frequented with enthusiasm.

Banine slightly revised the text of Days in the Caucasus and republished it in France in 1985. It is the 1985 version that has been translated here. Banine wrote in French, though she spoke Russian fluently and grew up speaking Azerbaijani with her grandmother. Wherever Banine used an Azerbaijani, German or Russian expression in her memoir, I have preserved those words and added an English translation where needed.

The language of Azerbaijan is known as Azerbaijani, Azeri or Azerbaijani Turkish. Banine used the version Azri, so in the translation I opted for the closest equivalent in English, Azeri.

Anne Thompson-Ahmadova

W e all know families that are poor but respectable. Mine, in contrast, was extremely rich but not respectable at all. At the time I was born they were outrageously wealthy, but those days are long gone. Sad for us, though quite right in the moral scheme of things. Anyone kind enough to show interest might ask in what way my family wasnt respectable. Well, because on the one hand it could not trace its ancestral line further than my great-grandfather, who went by the fine name of Asadullah, meaning loved by Allah. This proved very apt: born a peasant, he died a millionaire, thanks to the oil gushing from his stony land, where sheep had once grazed on meagre pickings. On the other hand because my family included some extremely shady characters on whose activities it would be better not to dwell. If I get caught up in the story, I might reveal all, though my interest as an author is at odds with my concern to preserve the last shreds of family pride.

So, I was born into this odd, rich, exotic family one winters day in a turbulent year; like so many historic years, this one was full of strikes, pogroms, massacres and other displays of human genius (especially inventive when it comes to social unrest of all kinds). In Baku, the majority of the population of Armenians and Azerbaijanis were busy massacring one another. In that year, it was the better-organized Armenians who were exterminating the

No one would have considered me capable of taking part in the work of destruction, but I clearly was, since I killed my mother as I came into the world. To escape the bloodshed, she had chosen to give birth in an oil-producing area in the hope that it would be quieter there; but in the chaos of the time she ended up giving birth in dreadful conditions and contracted puerperal fever. In addition, the house was cut off from outside help by a violent storm, compounding the confusion into which wed been plunged. Without the complex care that her condition required, my mother fought the illness in vain. She was lucid when she died, full of regret at leaving life so young and of anxiety at the fate of her loved ones.