Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III& Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

Helen Castor

ELIZABETH I

A Study in Insecurity

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Helen Castor, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design by Pentagram

Jacket art by Lucille Clerc

ISBN: 978-0-141-98089-8

For Ken, who is exactly perfectly right

Introduction

The Lady Elizabeth

15331547

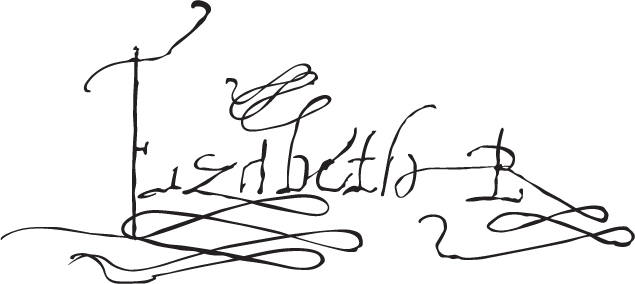

On the morning of Friday 19 May 1536, a woman in a grey silk gown climbed a newly built wooden scaffold within the precincts of the Tower of London. She spoke a few words to the large crowd that pressed silently around the platform, then removed her gable headdress and tucked her dark hair into a cap to expose her slender neck. She knelt, and one of her attendants tied a blindfold around her fine dark eyes. Sightless now, she asked God to have pity on her soul, repeating the prayer over and over. The man holding a sword behind her shifted slightly, and then, in one swift motion, severed her head from her body.

Until two days before she died, Anne Boleyn had been Queen of England. On 17 May the Archbishop of Canterbury had pronounced her three-year marriage to Henry VIII null and void. It was an annulment which made a legal nonsense of the trumped-up charges of adultery on which she had just been tried and convicted, but so clear was it that the king required both her death and the public erasure of their union that no one dared point out the incompatibility of the two verdicts. Still, she remained Marquis of Pembroke, the first woman to have been raised to the peerage in her own right, back in 1532, when the king had wanted nothing more than to marry her. Now, on this May morning, she became the first English noblewoman, and the first anointed queen, to die at the executioners hand. It was a shocking moment; and it left her only child facing a frighteningly unpredictable future.

Elizabeth was not yet three. When she was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533, her sex had been a disappointment to her parents, who had confidently expected God to give them a boy to vindicate Henrys repudiation of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, the mother of his daughter Mary. Nevertheless, Elizabeth had been proclaimed Princess of England, heir to her fathers throne (for the time being at least, until the day when her mother should give him a son). Since it had proved necessary for Henry to reject the authority of the pope in order to annul his marriage to Catherine and marry Anne, the baby girl was also the living embodiment of the religious revolution through which her father became, in 1534, Supreme Head of an independent Church of England.

That new title and new Church remained, but Anne had not provided Henry with a prince. As the king began to cast around for reasons why the woman with whom he had once been obsessed might not in fact be the queen God intended for him, her enemies set to work to find some. And when Anne fell, Elizabeths status was drastically altered. The declaration that her parents marriage had never been valid left her a bastard, like her half-sister Mary before her no longer the heir to the throne, nor a princess, but simply the Lady Elizabeth. Shortly afterwards, the line of succession was at last established elsewhere, with the arrival of the longed-for male heir, Edward, born in 1537 to Jane Seymour, the new wife Henry married less than a fortnight after Annes death.

However, there was nothing straightforward about Elizabeths revised position as the kings illegitimate daughter. Despite the fact that, formally, Henry professed to believe that Anne had committed adultery with five men, one of them her own brother, he never showed any sign of doubt that Elizabeth was his child and physically there was a strong resemblance, since the little girl had inherited his striking auburn hair and fair skin along with her mothers dark eyes. Nor, clearly, was she a mere by-blow, the product of some fleeting court dalliance. She and her half-sister Mary had each been born to an anointed and crowned Queen of England Anne had been six months pregnant with Elizabeth when she sat in state at her coronation in Westminster Abbey even if their mothers had later, in turn, been stripped of that title. And as the years went on, Henry enshrined the ambiguities of his daughters histories in statute law. The Act of Succession of 1544 named Mary and Elizabeth as royal heirs to their half-brother Edward, while at the same time Henry continued to insist, in all other contexts, on their bastardy.