RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

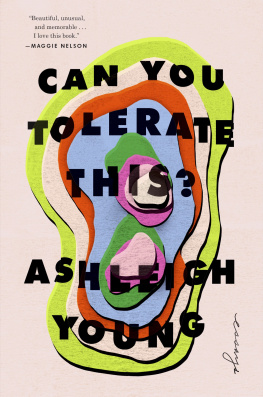

Copyright 2018 by Ashleigh Young

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

This book, in different form, was originally published in New Zealand by Victoria University Press, 2016.

The following essays were previously published, in different form:

Black Dog Book in Sport; Wolf Man in Landfall; Katherine Would Approve in Five Dials; Sea of Trees in Griffith Review; Anemone in Tell You What: Great New Zealand Nonfiction 2017, edited by Susanna Andrew and Jolisa Gracewood (Auckland University Press).

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint: Frank OHara, excerpts from Adieu to Norman, Bon Jour to Joan and Jean-Paul, from Lunch Poems. Copyright 1954 by Frank OHara. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of City Lights Books, www.citylights.com.

All of JP Youngs lyrics and correspondence are reprinted with his kind permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Young, Ashleigh, author.

Title: Can you tolerate this? : essays / Ashleigh Young.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017057498| ISBN 9780525534037 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525534051 (ebook)

Subjects: | LCGFT: Essays.

Classification: LCC PR9639.4.Y67 C36 2018 | DDC 824/.92dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017057498

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Cover design and art: Grace Han

Version_2

for Ngaire and Kiwa

contents

bones

It stands silently and elegantly and reveals its secrets if you ask the right questions.

Dr. Frederick S. Kaplan, orthopedic surgeon, authority on fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, 1998

Harrys first skeleton was the one he was born with. That was the healthy skeleton of a small boy. The only odd thing about this skeleton was that it had a bulbous bony protrusion on the left big toe; aside from that it was ordinary. His bones were ordinary bones: they were made of living cells and had marrow inside them, like the bones of fish, birds, mammals. Theres a photograph of Harry as a six-year-old, wearing shorts and a T-shirt, knobbly-kneed, with a lopsided smile and sticky-out ears. His blond hair is roughed up like hes just come in from running around or riding a bike outside with his sister Helene.

It was around the time of this photograph that a second skeleton began to grow around Harrys first skeleton. This bone, too, was ordinary bone. But it was heterotopic: in another place, the wrong place. The only time in our lives that ossificationthe transformation of cartilage into boneshould occur is when we are inside the womb. No new bones are supposed to grow once a person is born. They are supposed to be whole then. But it was as if this second skeleton of Harrys was working to shelter the first, as if the first was too fragile to continue going along on its own. If Harry hurt himselfif he broke his leg or stubbed his toehis body repaired itself by growing bone in the place where he had been hurt. It took a few days or weeks for the bone to appear. The only way his body knew how to heal was to harden, so afraid it seemed of leaving any part of him vulnerable.

There are four further photographs of Harry, all of them medical photographs taken in front of a blank wall, and in all of them Harry is in his underwear so that the form of his body can be clearly documented. At nine years old he is still smiling, and he seems braced in position by choice; his slightly crooked stance makes him look mischievous, like any nine-year-old. This is the last photograph in which he is able to raise his head to look directly at the camera. At eleven, thirteen, and twenty he is curved. Something seems to ripple in bigger and bigger waves under his skin. His eyes are lowered to his hands, as if he is concentrating on getting himself out of handcuffs.

As stark as these photographs are, they also show grace. Harry looks poised, as if about to raise his arms above his head and pirouette. His head and torso curve to the left, a delicate bow. Even as he is wracked and pushed about by his new skeleton, he flows.

Whenever Harrys physicians cut the new skeleton away, it would grow back forcefully over the next few months, as if in a panic. Soon it bound him tightly. Bone covered his back like a cracking cocoon. It welded his upper arms to his breastbone so that his arms hovered magician-like in front of his body. Bone wrapped itself in layers around his skull. Delicate columns of bone, like stalactites, fused his head to his neck, forcing him to stare at the ground. One of his legs was bent back, as if he were forever about to kick a ball, as if all the world were waiting in a grandstand around him. He could still move about by shuffling along with a cane. But when he was twenty, when his mother could no longer care for him, he went to live at a nursing home in Philadelphia called the Philadelphia Home for Incurables.

In his thirties, ossification reached Harrys lower jaw, which became locked to his skull, leaving him unable to speak. He couldnt brush his teeth, cough, stick out his tongue, lick an envelope or his own lips, whistle, or eat. He lay in bed at the home, a diagram of himself, as if his second skeleton wanted to fuse him to a single spot and keep him safe there. He should never move haphazardly through the world like others did.

It was six days before his fortieth birthday that Harry died. His physicians took his body, as Harry himself had wished: bequeathing it to science would give meaning and depth to medical and scientific research on FOP for decades. Following on from the few photographs of Harry as a boy and a young man, there are many, many photographsfrom all angles and proximitiesdepicting only his skeleton.

He stands today in the Mtter Museum of the College of Physicians in Philadelphia, the city in which he was born. Hes not far from the plaster death cast of Chang and Eng, the conjoined twin brothers who died in 1874, aged sixty-two. In life, a seven-inch-long ligament joined them at the chest. The liver they shared is displayed beside them in a glass jar, preserved in formalin.

Harry is alone inside a glass case. He stands on one leg, as he stood in life, his other leg bent behind him. He was easy to put together. Ordinary human skeletons require fine wires and glue for articulationthe gentle drawing upward of the bones, so that they hold together and stand tall. Without the wires and glue, they tumble into a pile. Harrys skeleton stood tall without help, because the plates, sheets, ribbons, and thorns of his second skeleton fused him almost completely into one piece. You wouldnt know Harrys face or his handwriting or the sound of his voice, but even though he is faceless and silent, left alone he is self-supporting and strong. We can look on the contained explosion of his skeleton, the way it seems forever breaking but never broken. Physicians, scientists, and students return and return to it; they say he is their Sphinx. Harrys sister Helene comes each year to see him too, and to pay her respects.