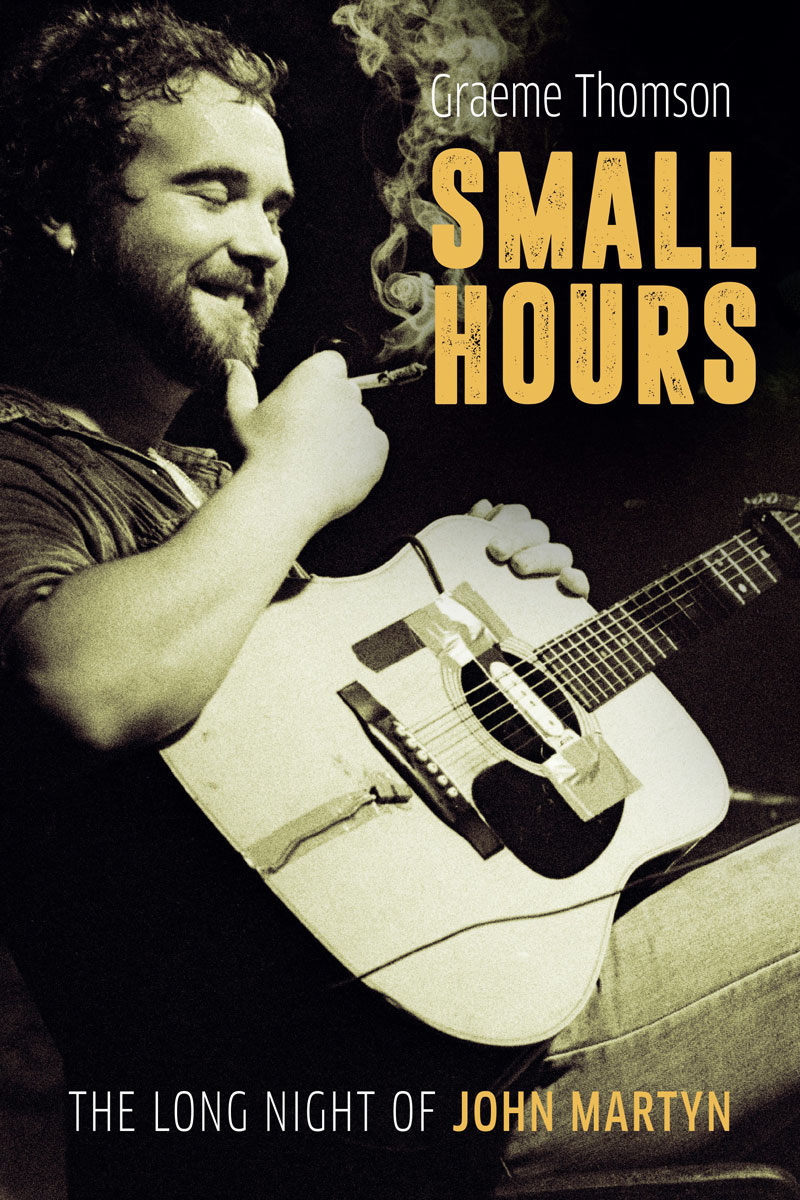

Graeme Thomson - Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn

Here you can read online Graeme Thomson - Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Omnibus Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

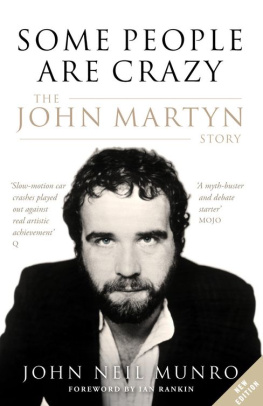

- Book:Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn

- Author:

- Publisher:Omnibus Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In the opening scene of the movie that will never be made of John Martyns life, the camera pans slowly across Island Records Basing Street studio. A band recently signed to the label is playing an informal showcase. Fellow artists have come to watch, listen, drink, gossip and offer encouragement.

Through the smoke and sound, a Gorgon crown of golden curls bobs up, then down, then up again. Beneath it is John Martyn. He snakes between the throng, bopping lightly to the music, tossing out jokes, trying on voices, cultivating connections, curling an arm around familiar shoulders. The music never stops and neither does he.

Island in the early Seventies was something like an extended family. Musicians gathered at its offices at 22 St Peters Square in Hammersmith, at the Cross Keys pub across the road, or in the studio at 810 Basing Street in Notting Hill. By habit and through choice, they played on each others records, toured together, often lived together.

If Chris Blackwell was Islands unflappable paterfamilias, then John Martyn was the favoured wayward child. Full of wit and bounce and bite, he pushed his luck into corners and charmed, or slugged, his way out almost every time.

There is something hugely attractive about a young musician in bloom, on top of their game and acutely aware of the fact, confident bordering on arrogant, flying not just with their talent, but the idea of their talent, the possibilities stretched out before them like the outline of a new country. It doesnt last it cannot and should not last but for a long moment it seems to be that everything they do possesses an intuitive, essential rightness. Their spell charms almost everyone it touches, even if it touches only relatively few. It is the kind of meaningful contact that travels deep rather than wide.

Martyn in the first half of the Seventies was that artist. He and his music walked hand in hand in a kind of golden glow. The best vocalists sing like they speak; Martyn sang like he looked, in hazy, honey-coloured tones, barbed and fuzzy around the edges. He was stoned, certainly, but wired-stoned. Head spinning, feet twitching, fingers flashing; always in motion. Softness and abrasion. Irresistible, seductive, unsafe. He was so good he didnt trouble himself with the plain art of precision. He made it up anew each time. Martyn was the kind of artist you travelled towards with your heart in your throat, as you travel towards unrequited love or a fire in the woods.

He wrote, sang and performed simple songs with dazzling dexterity and an intensity that bordered on outright aggression. Rocking back and forth, slamming the strings with his index finger and thumb his great friend and foil Danny Thompson called him Badfinger his energy on stage was volcanic and confrontational: are you with me or against me?

Martyns best songs travel down, or up, or around and around, but rarely in a straight line. Melodies blossom then wilt. Time signatures stretch and snap. Rhythms steam, bubble and deliquesce. He loved water and used it again and again as a lyrical and musical motif. It is the element which best fits the sounds he created: ripples, waves, currents, eddies; rocks plunging, stones skimming, whirlpools boiling. He drew fat circles in wet sand, surrendered his anchor to tidal drift, echoed the irregular patter of snow-melt.

Having grabbed a foothold in the rather earnest Sixties folk scenes in Glasgow and London, he soon outgrew what he regarded as their limitations. Folk rock, when it soon came, was firmly 4/4. Martyn kept his own time. He immersed himself instead in spiritual jazz, skeletal blues, reverberating dub, pushing his guitar playing and his voice, stretching his capabilities. It did not carve a route to fame or fortune. He never had a hit single; a sole album scraped into the Top 20. It was just as well. Martyn sold as many records as his life could stand.

The art was magical and unerringly beautiful, fearsomely personal, feather-light and somehow pure. It was also capable of being coarse, aggressive, wayward and indulgent, not to mention repetitive and downright dull on occasion. Its great recurring theme is love, which, given the way Martyn lived his life, is not so much a contradiction as evidence that a sincere belief in the power of love is not the same thing at all as having the desire or the ability to practise that creed. It was certainly not enough to sustain him peacefully through the world, or to protect the world from him. The heart that was always present in his music was a divided one, the beauty mirrored by what Ralph McTell calls an awe-inspiring darkness. It didnt always require words. A divine, whirling rage is powerfully evident in Outside In, just as one can discern a profound commitment to some higher healing force flowing through Small Hours.

It must have been exhausting being the John Martyn that John Martyn presented to the world. So much so, one suspects that playing music was the only time he was able to get out of the way of himself, to allow himself a break, a breather. The great thing about music, he once said, is for those sections of my life that Im playing, I dont actually exist and Im quite convinced that, while other people are growing old during that time, Im not.

Even during the pauses on stage between songs he was on, jiving and joking, jousting with the audience, his band, himself. To watch him perform was to witness an unsettling dance between deep revelation and blunt, sometimes brutish, concealment. The music said too much, and he spent the rest of the time his life living it down. Some curse: to be so hopelessly in thrall to beauty as to fear it and seek constantly to undermine it. The innate prettiness Martyn possessed in his face, his voice, his music, his words was a gift he at first exploited and then actively mistrusted. In the end he simply destroyed it.

Lost inside the music, however, he dropped all fronts, and some purer form of his true self emerged a romantic, vulnerable soul, minded to love, curving towards peace, no stranger to tears. Did any musician in the Seventies fly so free as Martyn did on Bless The Weather, Solid Air, Inside Out, Live At Leeds and One World? Did any fall quite so far?

So much for the movie.

We were in the beer garden, John Martyn and me, and I could think of no useful means by which to measure the distance his life had travelled from his music. It was the autumn of 2005. Martyn had a little over three years left to live, and the hard fact of his mortality was cruelly apparent and yet somehow seemed absurd.

At this stage in the proceedings, fifty-seven years deep and scored with the irrefutable evidence of a long spell of hard weather, Martyn was a man who tested the limits of the powers of description. He tipped the scales at twenty-something stone, his huge face scarred, his fingers grey and pale and thick as butchers sausages. A plump pink abscess poked out from under his shirt. When he stood and leaned on his walking staff, he resembled a fallen Shakespearean king, a titan damned to a dotage of impotent rage. By now, he spent much of his time in a wheelchair.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn»

Look at similar books to Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.