A Death in San Pietro

ALSO BY TIM BRADY

Twelve Desperate Miles: The Epic World War II

Voyage of the SS Contessa

THE UNTOLD STORY OF

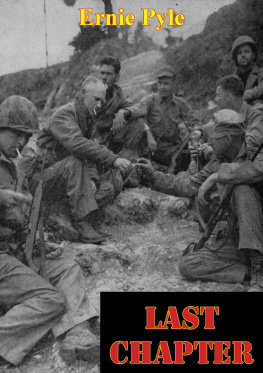

Ernie Pyle, John Huston,

AND THE

Fight for Purple Heart Valley

TIM BRADY

DA CAPO PRESS

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Copyright 2013 by Tim Brady

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Set in 12 point Adobe Garamond Pro by Marcovaldo Productions for the Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First Da Capo Press edition 2013

ISBN: 978-0-306-82215-5 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Susan, Sam, and Hannah

CONTENTS

MAPS

A Death in San Pietro

ONE UNIT OF SOLDIERS heading down the mountain, the other heading up. It was no easy task in either direction. Mt. Sammucro was a bare heap of rocks looming above the village of San Pietro: almost 4,000 feet high and so steep and craggy that the Italian mules carrying supplies to the American forces at its summit could only make it to the tree line, a third of the way up, before giving way to the sharp boulders and scree.

The constant precipitation on the mountain that fall, a mix of rain, sleet, and snow, didnt make the travel any easier. The rocks were greasy; the pebbly footing slipped away beneath combat boots. Both units were looking for a chance to pause among the hard ledges and catch their breath. Smoke a cigarette if they had em.

No one made a record of what the soldiers talked about that night, but there was business to discuss. Company B, moving up the mountain, would want to know the state of the defense above on the summit. Company I, moving down Sammucro, would be interested in what was going on at headquarters below. When would be the next assault on San Pietro?

There was a moment to talk about small things, too. Maybe something about the ironic circumstances that had brought both companies, each organized in neighboring small, south central Texas towns, to this Italian mountain just in time for Christmas 1943. Perhaps there was a passing mention of how the holiday would be celebrated back home.

In Belton, Texas, where Company I had been put together as a National Guard unit in the late 1930s, the Sunday school classes of the First Baptist Church were practicing a Christmas pageant, while the Presbyterians had already held theirs the Friday before. The Beltonian movie theater was showing Watch on the Rhine with Bette Davis.

Sixty miles to the northeast, in Mexia, Texas, the home base for Company B, rehearsals were under way for the annual Christmas concert held at the City Auditorium. The Black Cat Band would be performing Irving Berlins White Christmas to highlight their show. War bonds would be available for sale at the door.

Both local papers had plenty of war news, tooSoldier Letters Needed This Week for Dec. 24 News read one column, reminding mothers to get news of their boys overseas duty down to the paper if they wanted the reports to be printed by Christmas. But there was little mention of what was happening here in Italy, right on this mountain.

Both Companies B and I belonged to the 143rd Regiment of the 36th Infantry Division, part of the U.S. Fifth Army. They had arrived here together in Italy four months earlier; combat rookies, fresh from the port city of Oran, suddenly shoved out of their landing craft and onto the beaches of Salerno with no time to look back.

With the first splash of water came the terrible guns of war: the sputter of small arms fire, the endless scream of shells, the thump-whistle of mortars, and the deafening thunder of explosion after explosion. Dust and smoke and quaking ground. What remained for the eye to comprehend when all was settled made no sense at all: misshapen dead men, gaping holes in the landscape, strong, steel vehicles now twisted and mangled in heaps, solid stone buildings turned to rubble.

Three weeks of this brand of hell followed the landing, then came a moment of relative quiet, when the men of the 36th were able to actually see the foreign land they had arrived at. Ancient ruins and vistas, as beautiful as any these boys from the hill country of south central Texas had ever seen, dotted the landscape. They had heard of Vesuvius and Pompeii, Naples and the Isle of Capri. Now here they were amidst striking blue seas and dappled sunlight that glimmered through lemon trees and olive groves. There was finally time between the action to look, to contemplate the land, to eyeball its people: dirty, hungry, brutalized by war, yet grateful, oddly enough, given the amount of ammunition the Allies were dropping on their homes and villages, for the presence of the Americans.

But the 36th returned quickly to war. After Salerno and Naples came the abysmal crossing at Volturno River. And then rain and more rain, until now when they faced this line of mountains. The imposing range ran all the way across the mid-section of Italy from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian Seas. High, rock-strewn piles, bare of vegetation on the tallest of them, including Sammucro. Just great hunks of boulders, sharp artes, crags, ridges, and cliffs; but plenty of places for the young men on both sides of the fighting to crouch from the bullets and mortars, lean deep as possible into the shade of those rocks, and try to breathe deep, slow the racing of their hearts.

The goal of the Americans lay just on the other side of Sammucro, designated Hill 1205 on army maps. There the Liri Valley spread out between the line of hills and mountains, and pointed northwest toward Rome. Down its center was Highway Six, the ancient Via Latina, which every Italian military leader from Caesar to Garibaldi to Il Duce knew as the link between the boot of Italy and its heart. This was the Allied treasure, though even now some wondered why. What was so important about the Liri Valley, about Rome, about whatever would come next in Italy? Wasnt the real goal to get to Berlin, and would that ever happen over the Alps?

Next page