YOU NEVER SAW SUCH A THING,

SAID GAUCHE, IMPRESSIONABLE LEFTENANT HOOPER.

I n the opening pages of Evelyn Waughs Brideshead Revisited, a wartime detachment of Royal Marine Commandos bivouacs in the moonless night on the grounds of some vast but only glimpsed and half-suspected English country house. When the troops are roused at dawn, disoriented by the long train ride, by fatigue and the morning mists, and harried by their corporals and sergeants, Hooper, a gauche, easily impressed young leftenant from the unfashionable Midlands, hurries to wake the world-weary and Old Oxonian protagonist of the novel, Captain Charles Ryder, an older man disillusioned with the army.

Atwitter about their lavish new surroundings, the provincial Hooper rhapsodizes about what hes seen so far of the strange estate, its palatial extent, its wonders and splendors, its supposed riches.

Great barrack of a place. Ive just had a snoop around. Very ornate, Id call it. And a queer thing, theres a sort of R.C. church attached. I looked in and there was a kind of service going onjust a padre and one old man. I felt very awkward . Theres a frightful great fountain, too, in front of the steps, all rocks and sort of carved animals. You never saw such a thing, he assures Ryder.

Yes, Hooper, I did. Ive been here before .

Oh well, you know all about it. Ill go and get cleaned up.

Ryder had been there before, we realize; he did know all about it. The great estate was called Brideshead, and it was there that Captain Ryder had been young and in love.

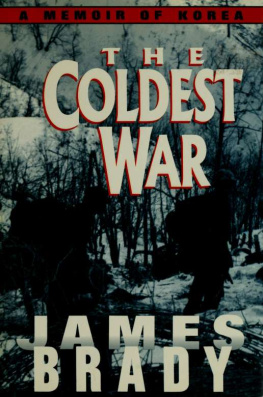

Like Charles Ryder, I too was an aging former captain of Marines who had once gone to war, and there found love.

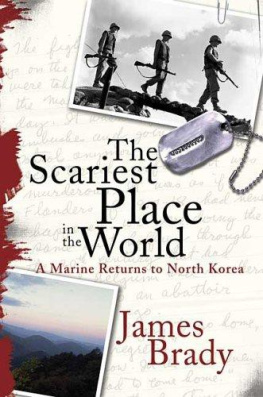

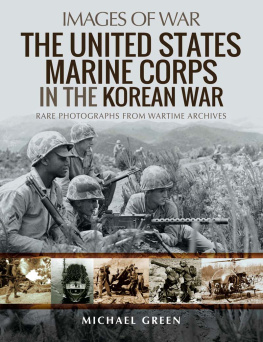

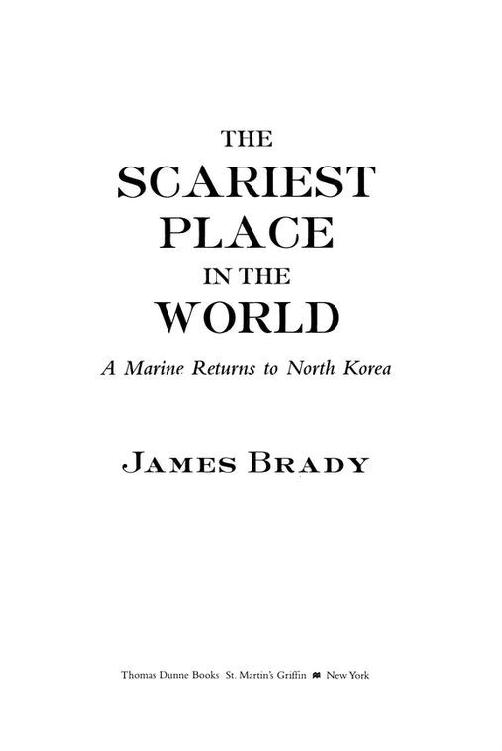

Ours wasnt a towering and noble crusade such as World War II, but small and brutish, rather old-fashioned, on the other side of the world in the mountain snows and stinking paddies of a strange, antique Asian land, a long-ago little kingdom invaded and ransacked by marauding enemies over the millennia, and left lone and forlorn. By todays high-tech, more discriminating standards, it was a primitive war, to which half a century ago some of us went almost eagerly and with a certain dash, having missed the Big War, and feeling left out. I fought there, in Korea both North and South, as a twenty-three-year-old infantry officer of American Marines.

It was hard fighting by foot soldiers, often at hand-grenade range, against the tough little peasant army of a local warlord named Kim Il Sung, whod learned his trade as a battalion commander in the Soviet Red Army in the Nazi war. For three years we fought Kim and his allies, the forty divisions of Chinese Communist regulars, killing plenty of them, and saving the marginally democratic country of South Korea, enabling its economic miracle.

But we took our losses.

In the three years of that war, from June of 1950 to July of 53, thirty-seven thousand Americans were killed, infantry soldiers and Marines mostly. Thirty-seven thousand dead in thirty-seven months. Put it in context. While this is being written in the summer of 2004, the Iraq war has been on for eighteen months and a thousand Americans have died. In Korea, a thousand of us were killed every month, month after deadly month for three years.

This book is about that war and the Marines who fought it.

It is also about a college kid from the Brooklyn fishing village of Sheepshead Bay and his love for the Marine Corps and the men with whom he campaigned: the classy university types, the roughnecks and the poets, the sophisticates and the hicks, the salty regulars and the freshly graduated, and what the Marines called the Old Breed, the hard old China hands. It is about those who died, those who lived, some of them scarred forever, and the happy few who survived Korea and went on to fortune and occasionally to fame.

The kid, as he was then, was a Marine rifle platoon leader, a member of an exclusive fraternity.

In the entire Marine Corps of two divisions and 175,000 men, there are only 162 rifle platoons, each of them commanded by a young second lieutenant, for it is the most lethal job description in the Corps, a young mans work. After enough combat, men grow too wise to want to command a platoon. When Marines assault a beachhead or a hilltop or a fortified position, it is the rifle platoons that lead the way, that attack and smash, and sometimes break against, the enemy lines. The mortality rates are such that some of his forty-five men may never even get to meet their platoon leader before he is wounded, killed, or replaced. This is about one of those replacement lieutenants, who arrived Thanksgiving weekend of 1951 in the Taebaek Mountains of North Korea, and was given a Marine rifle platoon to lead.

And it is about the place where he fought as a boy, the auld enemy he fought against, about his comrades in arms, and what happened to them after the fighting, all of this now seen through the focus of age at his house on Further Lane, where the lovely three-centuries-old beach town of East Hampton borders the ocean and where, in the night, he can hear the Atlantic combers crashing on the sand.

The kid survived the war to become a newspaperman, covered the Senate during LBJs era, came to know Jack and Bobby Kennedy, became a foreign correspondent, got to live in Paris and London, was an editor and publisher, went on television, learned about fashion, and about life, at the knee of Coco Chanel, knew Joe Heller and Truman Capote and Mailer, worked for Rupert Murdoch and had breakfast with Kate Hepburn, met the Queen, once rode in an ambulance with a badly burned Kurt Vonnegut, watched Dali having cocktails at the Ritz, interviewed Malraux, and attended Ikes and de Gaulles press conferences. On a Budget Day, from the press gallery of the House of Commons, he actually saw Churchill, bent and fat, deaf and very old. And at Cape Kennedy covering the Apollo 11 launch, he attended in one of those mammoth, echoing hangars a cocktail party with von Braun and Charles Lindbergh, the entire history of manned flight in the same room, the German mobbed by flatterers and Lindy in his muted gray business suit, alone and unnoticed, but graciously willing to chat when a journalist approached, bashfully, to say hello and talk a little about flying.

Yet nothing he ever did in his life, except for having children and making a life as a writer of books, quite matched the intensity, the gravitas and sheer excitement of fighting in North Korea as a rifle platoon leader of Dog Company Marines under Captain John Chafee in 1951-52.

It all happened a long time back when he was young, and half a century later in his seventies, listening to the sea at night, he remembers.