Table of Contents

by Martin Scorsese

: Nick Carter, Master Detective (1939) and Phantom Raiders (1940)

: The Comedy of Terrors (1963) and War-Gods of the Deep (1965)

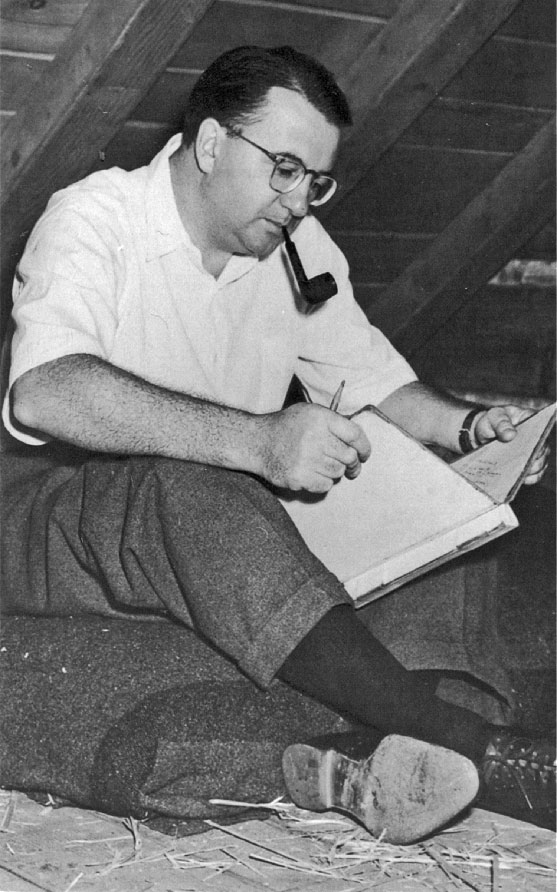

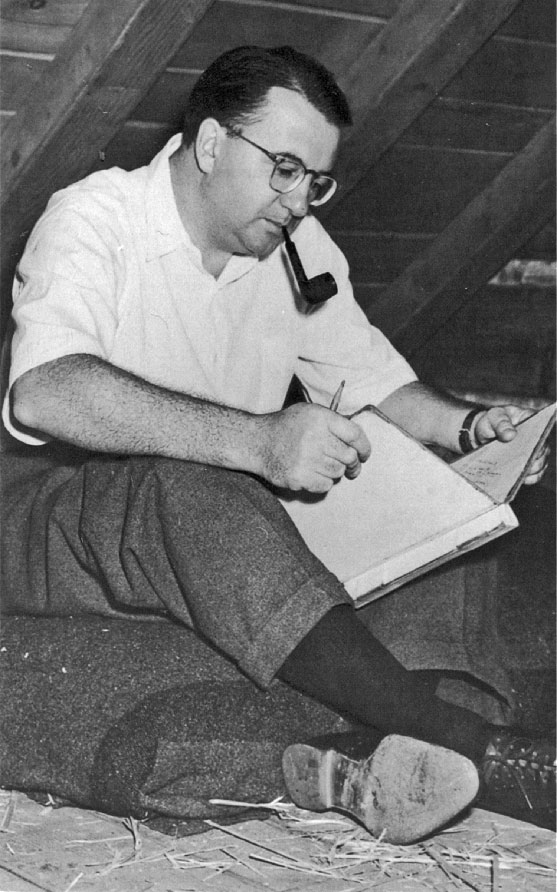

Frontispiece: Jacques Tourneur during the shooting of Days of Glory (1944). Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

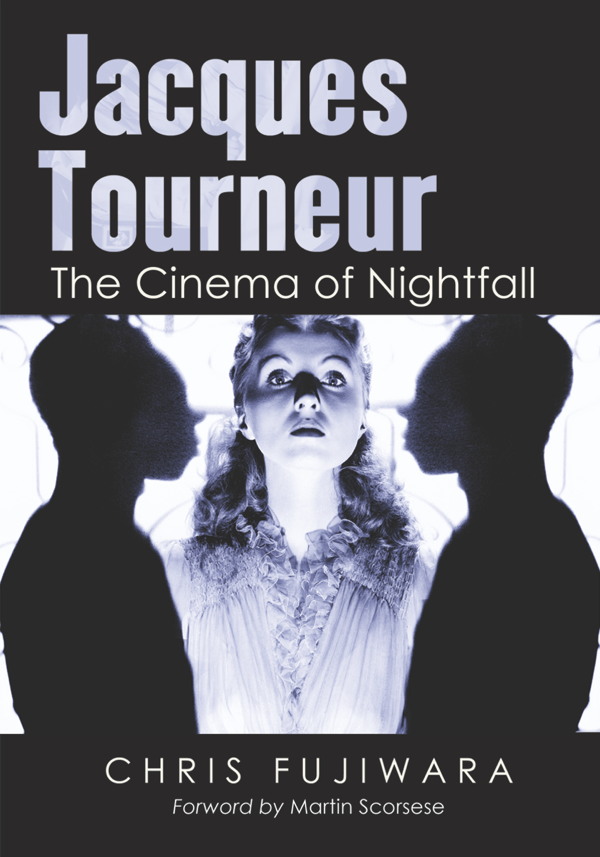

Fujiwara, Chris.

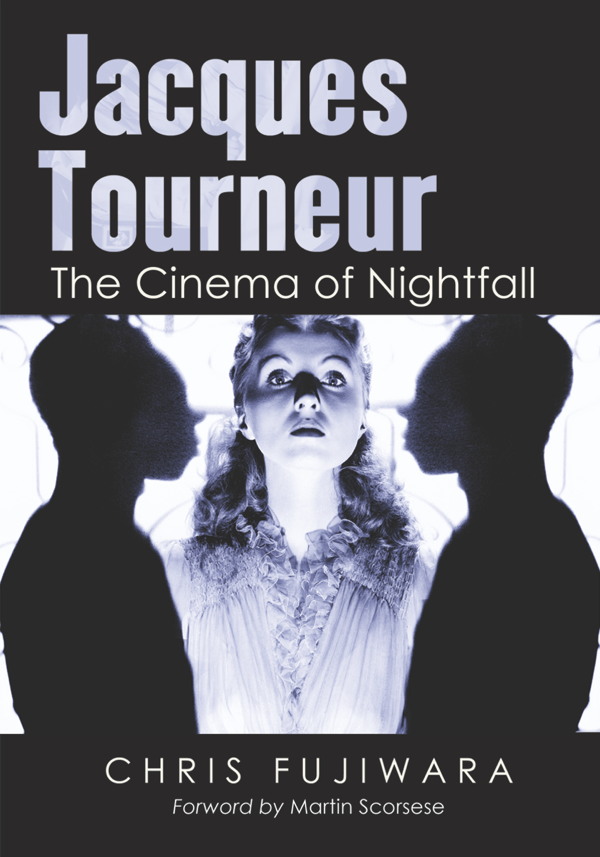

Jacques Tourneur : the cinema of nightfall / by Chris Fujiwara ;

with a foreword by Martin Scorsese.

p. cm.

Filmography: p.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBn 978-0-7864-6611-5

1. Tourneur, Jacques, 19041977Criticism and interpretation.

I. Title.

PN1998.3.T6F85 2011

791.43'0233'092dc21

98-16113

1998 Chris Fujiwara. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover design by David K. Landis (Shake It Loose Graphics)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Julia

Acknowledgments

For responding to my inquires about Jacques Tourneur, and in some cases for providing me with unpublished materials, I am indebted to Jean-Claude Biette, Jack Elam, Richard Goldstone, Bert and Charlotte Granet, Peter Graves, Jane Greer, Jacques Manlay, Rhonda Fleming Mann, Virginia Mayo, Gregory Peck, Philippe Roger, Robert Schiffer, George Sidney, Robert Stack, Maurice Vaccarino, Paul Valentine, and Michael Henry Wilson.

For encouragement, support, consultation, and various servicesincluding providing prints, videotapes, and textual materialsI wish to thank Ed Bansak, Diego Curubeto, John Gianvito, Scott Hamrah, Kent Jones, Bill Krohn, Tim Lucas, Juan Mandelbaum, Dennis Millay, Federico Muchnik, Charlotte Fay Pagni, Max Schaefer, Martin Scorsese, Tom Weaver, and my mother and father.

For putting me up and driving me around L.A., I am grateful to Marilynn Eden; Mark, Lisa, and Tyler Engel; Kenny Fujiwara; and Patty Masumi.

I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the staffs of the following archives and research collections: the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (Faye Thompson); the Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division (Rosemary Hanes, Madeline Matz); the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; Special Collections, University Research Library, University of California at Los Angeles (Brigitte Kueppers, Ray Reece); the UCLA Film and Television Archive; the Cinema-Television Library and Archives of the Performing Arts, University of Southern California (Ned Comstock); and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

Foreword

by Martin Scorsese

Its appropriate that so many of Jacques Tourneurs movies deal with the supernatural and the paranormal, because his own touch as a filmmaker is elusive yet tangible, like the presence of a ghostin a way, you could say that Tourneurs touch is so refined and subtle that he haunts his films. Its as though he cast a spell over each project, from a movie that actually deals with the supernatural like Cat People to one that only seems to deal with it, like The Leopard Man, to a western like Canyon Passage, a period piece like Experiment Perilous, a noir like Out of the Past or a routine B assignment like Nick Carter, Master Detective. Which may be the reason why he remains so under appreciated. Tourneur was a great director, fully deserving of the thoroughly researched and perceptive treatment he receives from Chris Fujiwara in the pages that follow. But in comparison to the directorial stars of American cinemaHitchcock, Ford, Capra, Hawkshe remains a shadowy figure, apt to portray himself in public as a craftsman and content to work in B-movies. Throughout his long career, Tourneur stayed in what critic Manny Farber called termite territory. He never made grand statements and he never worked with large budgets or big stars. He cultivated the most fleeting and elusive aspects of experience, things that other filmmakers would never bother with but that, for Tourneur, were the essence of movies.

Tourneur was an artist of atmospheres. For many directors, an atmosphere is something that is established, setting the stage for the action to follow. For Tourneur it is the movie, and each of his films boasts a distinctive atmosphere, with a profound sensitivity to light and shadow, and a very unusual relationship between characters and environmentthe way people move through space in Tourneur movies, the way they simply handle objects, is always special, different from other films. Bertrand Tavernier and Jean-Pierre Coursodon have noted that Tourneur tended to record dialogue at low levels, and he always encouraged his actors to underplay (which must be why he preferred to work with minimalists like Robert Mitchum, Dana Andrews, or Victor Mature) and to move at a slightly slower pace than usual. Places, objects and atmospheres are living presences in his work, while emotion and drama speak very softly, the better to show how deeply they are affected by the physical world around themwhich is why I think the films have such a hypnotic quality. Farber, again, might have been the first person to describe the way that Tourneur equalized people and objects, in his obituary for the great producer of Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie (Tourneurs favorite), Val Lewton.

Take Canyon Passage, an example of the short-lived but very interesting sub-genre of the noir western and a picture thats very special to me. Its one of the most mysterious and exquisite examples of the western genre ever made. When you think of westerns you immediately picture the plains or the desert, vast spaces that stretch on and on for miles. But this film, Tourneurs first in color, is set in a small town in the mountains of Oregon, and it is lush, green, muted, and rainy (one of the first scenes in the movie shows the cramped main street of Portland turned into a muddy bog by a downpour). Even the open spaces in this movie are just small mountain clearings. If you study Canyon Passage carefully youll see that Tourneur constantly composes diagonally into small spaces, showing people walking up or down inclines, and it gives you the feeling that this is a real settlers town. One of the first shots in the movie is of Hoagy Carmichael singing a song as he slowly rides his donkey up the steep little main drag of the townits repeated in the end (its in this movie that Carmichael also sings Ole Buttermilk Sky, a song that instantly transports me back to my childhood whenever I hear it). And it embodies the muted, understated beauty of the entire film.

There are some beautiful set pieces in Canyon Passage like the Indian attack and the barnraising, but the overall tone is so carefully controlled that every small variation or nuance has an impact. Thats what makes Tourneurs films so unsettling, this strange undercurrent that runs through every scene but that somehow enhances the dramatic impact of the whole film. For instance in the famous sequence in Cat People where Jane Randolph walks alone to the bus stop in Central Park, the evenness of the tone keys the viewer to the subtlest changes in sound and light to such an extent that the climax of the scene (hair-raising each time you see it) is the sound of a bus hitting its air brakes. In

Next page