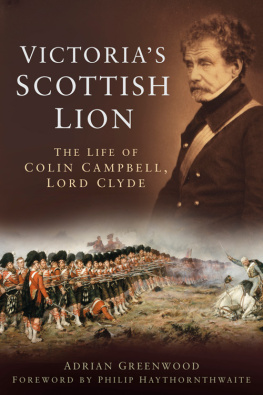

I would like first to thank Philip Haythornthwaite, who not only very kindly offered to write the foreword, but also checked the book before publication. The following also read the manuscript and offered invaluable advice: Mary Chapman, Jonathan Hellewell, Leo Lester, Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm McVittie, Nigel Smith, David Sorrell, Dunstan Speight and Matt Wheeldon. At The History Press Shaun Barrington, Lauren Newby and Jo De Vries, and their editors and designers, have all put in a great deal of work preparing the book for publication and deserve praise.

I am very grateful to Her Majesty the Queen for permission to quote from the various sources made available to me at the Royal Archives. Also thanks to the staff of the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the Caird Archive and Library at the National Maritime Museum, Lady Margaret Hall College Library, the National Archives, the National Library of Scotland, National Museums Scotland, the Oxford Union Society, the Templer Study Centre at the National Army Museum, the Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum, the School of Oriental and African Studies Library, Spinks, the Staffordshire Regiment Museum, Wigan Archive Services and the Rector, Librarian and staff of the High School of Glasgow. I would also like to thank Peter Gawn for his help and research concerning Campbells time in Gosport.

Contents

: The Peninsular War The Battle of Vimeiro

The Retreat to Corunna Walcheren

: The Battle of Barrosa Hill The Battle of Vitoria

The Siege of San Sebastian The Crossing of the Bidassoa

: The West Indies The Demerara Slave Revolt

Ireland and the Tithe War The Chartists

: The First Opium War The Battle of Chinkiangfoo

The Treaty of Nankin Chusan

: The Punjab Ramnuggur Action at

Sadoolapore The Battle of Chillianwala The Battle of Goojrat

: The North-West Frontier Dalhousie

: The Crimean War The Battle of the Alma

: The Battle of Balaklava The Siege of Sebastopol

: The Indian Mutiny The Relief of Lucknow

: The Battle of Cawnpore Defeat of the Gwalior Contingent

: The Taking of Lucknow Pacification of India

: White Mutiny Second Opium War Return to Britain

Appendices

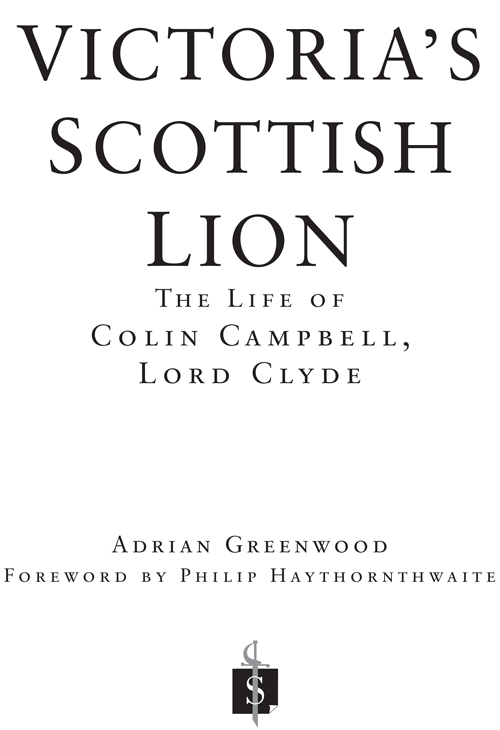

The officer corps of the British Army of the late Georgian and early Victorian periods was drawn from a diversity of backgrounds. Contrary to one perception, the aristocracy represented only a minor, if influential, component: more prolific were those drawn from the lesser gentry, minor landowners and the professional classes, and it was possible for a soldier of even humbler origins to rise to high rank if he possessed the talent and the luck. During the years of the Peninsular War, for example, no less than 803 rankers were commissioned as officers, although it was difficult for them to prosper after the war if devoid of either influence or financial resources. The opportunities were a degree more auspicious for those who had some military connections, and one of the most remarkable officers from a relatively modest background is the subject of this study: Colin Campbell.

From a family more artisan than gentry, Colin Campbell had a reasonable education and was commissioned while still a boy. He began to learn his trade during a gallant career in the Peninsular War but, in common with many junior officers, Campbells promotion was slow in the limited opportunities for distinction following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. However, he served widely and clearly capably until he became famous for his command of the Highland Brigade in the Crimea, and, following that, in higher command in India, where he reached the pinnacle of his reputation.

In the pantheon of military heroes of the Victorian era, Colin Campbell was unusual, and while he may not have been among those of the first rank as a tactician, he surely was in terms of the rapport he established with those under his command. Fairness and understanding seem to have dictated his conduct, as related by a number who encountered him. William Munro graduated as MD from Glasgow in 1844 at the age of 22 and joined the 91st Foot as assistant surgeon in the same year. Ten years later he was appointed surgeon to the 93rd (Sutherland) Highlanders and shortly after joining his new regiment in the Crimea first met Campbell. As an experienced officer his observations on his commander are significant:

on being introduced to him, he shook me kindly by the hand, and bade me to look well after my regiment as it would soon need all my care and attention. he was the picture of a soldier; strong and active, though weather-beaten. Ever after my first introduction to him, in the Crimea and in India, Sir Colin was kind and friendly to me.

When recalling Campbells participation in the action at Balaklava, notably that involving the 93rd that became known as the Thin Red Line, Munro observed that after the regiment had fired a couple of volleys at the approaching Russian cavalry:

The men of the 93rd at that moment became a little, just a little, restive, and brought their rifles to the charge, manifesting an inclination to advance, and meet the cavalry half-way with the bayonet. But old Sir Colin brought them sharply back to discipline. He could be angry, could Sir Colin, and when in an angry mood spoke sharp and quick, and when very angry, was given to use emphatic language; and such he made use of on that occasion. The men were quiet and steady at a moment.

Although not born in the Highlands, but from Glasgow, Campbell understood the Highlanders, who clearly adored him, and their esteem was reciprocated. Munro explained:

The men were very proud of Sir Colin as a leader, and were much attracted to him also, and for the following reason. He was of their own warlike race, of their own kith and kin, understood their character and feelings, and could rouse or quiet them at will with a few words He lived amongst them, and they never knew the moment when, in his watchfulness, he might appear to help and cheer or to chide them. He spoke at times not only kindly, but familiarly to them, and often addressed individuals by their names, for long use and constant intercourse with soldiers had made his memory good in this respect. He was a frequent visitor to the hospital, and took an interest in their ailments, and in all that concerned their comfort when they were ill. Such confidence in and affection for him had the men of the old Highland brigade, that they would have stood by or followed him through any danger. Yet there was never a commanding officer or general more exacting on all points of discipline than he.

Another 93rd Highlander, William Forbes-Mitchell, quoted an example of Campbells memory for faces before the assault on the Sekundrabagh. A Welsh sergeant of the 53rd named Joe Lee, who had served previously under Campbell:

presuming an old acquaintance, called out, Sir Colin, your Excellency, let the infantry storm and well soon make short work of the murderous villains! Sergeant Lee was known by his nickname, Dobbin, and Campbell remembered even this, asking, Do you think the breach is wide enough, Dobbin? When the attack was mounted the 4th Punjabis in the first wave faltered, and as soon as Sir Colin saw them waver, he turned to Colonel Ewart, who was in command of the seven companies of the Ninety-Third and said, Colonel Ewart, bring on the tartan let my own lads at them! Before the command could be repeated or the buglers had time to sound the advance, the whole seven companies, like one man, leaped over the wall, with such a yell of pent-up rage as I had never heard before or since.

For all the rewards bestowed upon him, Campbell seems to have remained level-headed, even modest. On his first encounter with the 93rd after he had been elevated to the peerage, the regiments pipe-major, John MacLeod, said, I beg your pardon, Sir Colin, but we dinna ken hoo tae address you noo that the Queen has made you a Lord. Campbell replied, Just call me Sir Colin, John, the same as in the old times; I like the old name best.

Next page