ABOUT THE BOOK

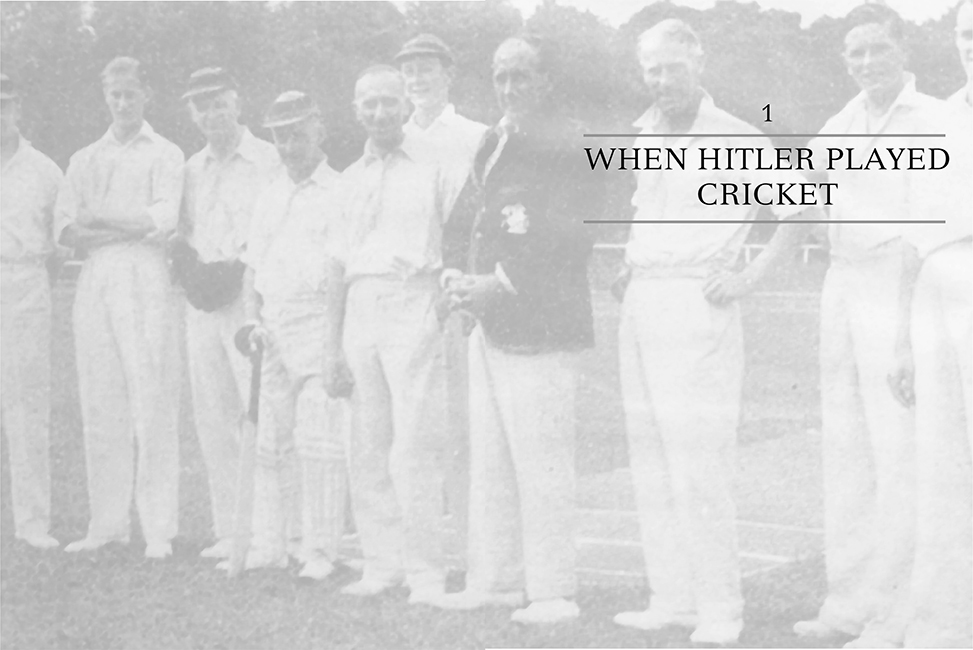

Adolf Hitler despised cricket, considering it un-German and decadent. And Berlin in 1937 was not a time to be going against the Fhrers wishes. But hot on the heels of the 1936 Olympics, an enterprising cricket fanatic of enormous bravery, Felix Menzel, somehow persuaded his Nazi leaders to invite an English team to play his motley band of part-timers.

That team was the Gentlemen of Worcestershire, an ill-matched group of mavericks, minor nobility, ex-county cricketers, rich businessmen and callow schoolboys, led by former Worcestershire CC skipper Major Maurice Jewell. Ordered not to lose by the MCC, Jewell and his men entered the Garden of Beasts to play two unofficial Test matches against Germany.

Against a backdrop of repression, brutality and sporadic gunfire, the Gents battled searing August heat, matting pitches, the skill and cunning of Menzel, and opponents who didnt always adhere to the laws and spirit of the game. The tour culminated in a match at the very stadium which a year before had witnessed one of sports greatest spectacles and a sinister public display of Nazi might.

Despite the shadow cast by the cataclysmic conflict that was shortly to engulf them, Dan Waddells vivid and detailed account of the Gentlemen of Worcestershires 1937 Berlin tour is a story of triumph: of civility over barbarity, of passion over indifference and hope over despair

CONTENTS

Also by Dan Waddell

Fiction

The Blood Detective

Blood Atonement

Selected non-fiction

And Welcome to the Highlights: 61 Years of BBC TV Cricket

Who Do You Think You Are? The Genealogy Handbook

For more information on Dan Waddell and his books, see his website at www.danwaddell.net

FIELD OF SHADOWS

Dan Waddell

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

www.transworldbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

in 2014 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright Dan Waddell 2014

Dan Waddell has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Photos and illustrative material used courtesy of Peter Robinsons family and Oliver Ohmann. Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Version 1.0 Epub ISBN 9781448170098

ISBN 9780593072615

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk

The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For my father, Sid Waddell (19402012)

PROLOGUE

BERLIN IN JULY 1945 was a city in ruins. Fires burned and the bodies of soldiers, civilians and horses lay rotting where they had fallen; U-Bahn tunnels had been split open by bombs and those who peered in could see towers of corpses piled on one another. People moved among the smouldering buildings and houses like ghosts, foraging and hunting for food, while the four foreign armies who now occupied their city watched them and each other warily.

On a warm summer morning, a group of British soldiers were standing at a checkpoint in West Berlin. From the rubble, five middle-aged men trudged towards them. It wasnt an uncommon sight. The majority of young men had been killed in combat or captured by the Russians on their relentless, savage march into Berlin that spring and it had become a city of women, children and old men.

As the men approached, the soldiers could see they were gaunt and underfed. Leading them was a balding, serious-looking man in his mid fifties. The officer in charge watched them carefully as they drew near.

I wonder what this lot want? he said.

By virtue of simply not being Russian, the British had been well received in Berlin, but they were still cautious of those seeking vengeance for the tens of thousands of tons of bombs the RAF had dropped on the city. Yet instinct told the officer this forlorn group wasnt out for revenge.

The man with the serious face nodded a greeting and smiled. His clothes were worn and flecked with dust but his receding grey hair was slicked with pomade. The officer guessed that in another time he had probably been a man of some standing.

Good morning, the man said, in almost perfect English.

The British soldiers murmured a greeting in return.

Can we help? the officer asked, cutting to the chase.

The troops had become used to these missions, the locals shuffling from the ruins to beg for fresh water, cigarettes, medicines, some women even offering their favours in return for food all the things a conquering army might expect from a defeated people who had endured misery and suffering.

But this request would leave him open-mouthed.

Yes, the man replied. Could we play a game of cricket against you?

It contains the most human account of the quirks of my boyhood hero Geoff Boycott of any book Ive ever read. However, this was one of those rare times when my mind was more attracted to the thoughts of our greatest essayist than our greatest living Yorkshireman.

I had turned to Raffles and Miss Blandish, which Orwell wrote in 1944 in response to the increasing brutality of modern crime novels. As an occasional crime writer I found it interesting and couldnt remember reading it before. But it wasnt Orwells sophisticated analysis of the ethics of the detective story which intrigued me. It was the bit about cricket, a game Ive played since I was nine and still play now. The titular fictional hero, Raffles, was a gentleman villain. He also played cricket, which Orwell felt appropriate because it reflects something of the British character: In the eyes of any true cricket lover it is possible for an innings of ten runs to be better (i.e. more elegant) than an innings of a hundred runs... (This is one point on which, I sense, George and Geoffrey might disagree. Violently.)

Orwell goes on, controversially, to suggest cricket was predominantly a wealthy mans game before stating, even more controversially and somewhat blithely, that nearly all modern-minded people dislike it. I love Orwell and sympathize a great deal with his politics, but that comment had me muttering about dour lefties (of the political persuasion, not the Alastair Cook sort). But Orwell was setting up the next sentence on the sort of modern-minded people he was referring to. The Nazis, for instance, were at pains to discourage cricket, which had gained a certain footing in Germany before and after the last war.

That sentence intrigued me. In particular the part about how cricket had flirted with popularity in Germany before being crushed under the Nazi jackboot. How did they discourage it? How popular might cricket have become in Germany if Hitler had not seized power? And