For Joyce and For Larry

THE PLAUSIBLE IMPOSSIBLE is a term of art unique to cartooning. It is what holds Bugs Bunny up when he runs off a cliff, traverses a yawning chasm, and continues running on the other side, completely ignorant of the terrible fate that, except for a magical, momentary suspension of the laws of gravity, should have been his. It is the guiding comic principleat once thrilling and ridiculousthat lies at the heart of cartooning. This willing suspension of disbelief has a logic all its own. What keeps Bugs aloft, what makes the impossible plausible, is not looking down. It is a talent that eighty-nine-year-old Al Jaffee has displayed in his life as well as his art.

Al Jaffee enjoys a special relationship with the plausible impossible. For him it is more than a term of art; it is the story of his life. A rsum of Als formative years reads like a comic strip of traumatic cliff-hangers, with cartoons by Jaffee and captions by Freud. Al was separated from his father, abandoned and abused by his mother, uprooted from his home in Savannah, Georgia, reared for almost six years in a Lithuanian shtetl, and returned to Americaall by the time he was twelve years old. To this day, Al has a problem with trust. Everything is not going to be all right. I experienced so much humiliation that I became defensive about it. I am not trash. I am not garbage. Even homeless people, the lowliest of the low, have a strong sense of dignity.

Al wears his dignity like a carapace, a surprising cover, perhaps, for a man who finds so much about life ridiculous. He is always a gentleman, very well mannered without being a stiff, says illustrator-writer Arnold Roth, who has worked with Al and been his friend for decades. Still, Roth notes, There was always a certain sadness about Al. There were minor chords playing underneath. I knew nothing about the cause.

Nick Meglin, who was Als editor and friend at MAD for decades, was stunned when he learned that such a funny man had emerged from such a sad and humorless childhood. As a fan Im as grateful as I am baffled that he did.

Unless someone asks, Al doesnt talk about his childhoodnot the starved shtetl years in Lithuania or the indignities of living as a second-class citizen in other peoples houses. I dont volunteer the information. If somebody wants to know it, they have to get it from me.

His flamboyantly perverse youth has made him the man he is todaya satirist, an artist and writer, a raconteur, an arrested adolescent, and an aliena person uniquely qualified to introduce young Americans to the world of adult hypocrisy in the pages of a magazine called MAD.

1

THE WILD INDIAN

I was the terror of the neighborhood.

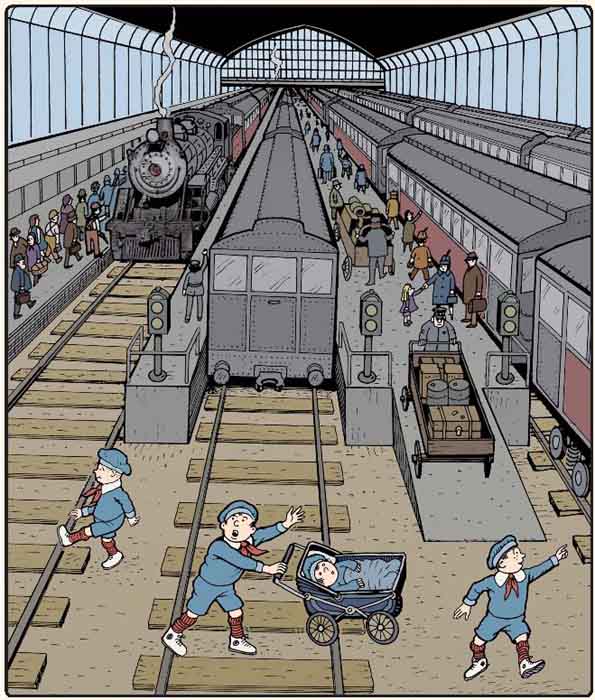

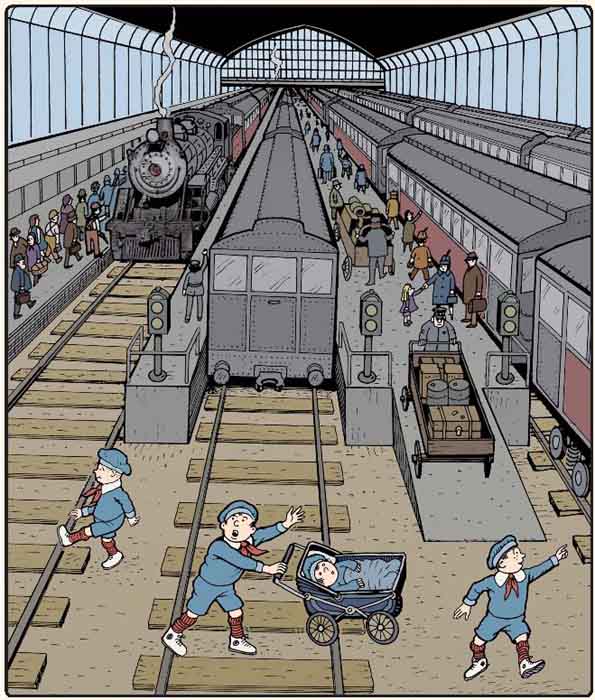

AL REMEMBERS the day his childhood ended. He, his mother, and his three younger brothers had just disembarked from the boat that had taken them on a long ocean voyage. The journey had started when he said an angry, tearful good-bye to his father in Savannah and had ended in this big, scary place with the funny nameHamburg. Was there a place, he wondered, called Hot Dog?

The Hamburg railroad depot was the biggest place he had ever seen. He was like Jonah in the belly of the whale, a hellish, frightening belly of soot, screeching metal, pumping wheels, and sulfurous coal smoke. Huge, dark engines crouched on the tracks, hissing and panting steam. A wilderness of rails ran out of the station until they were lost from view. If they followed one of these tracks far enough, Al wondered, would they lead to this place they were going called Lithuania?

Al had seen trains before, but never so many all at once. His father had always been with him in the train station in Savannah when they went together on Sundays to the Isle of Hope, an amusement park outside of the city. Al could remember standing with him on the platform. He could almost feel his fathers hands resting firmly on his shoulders, holding him safely in place, away from the tracks, while Al, thrillingly terrified, leaned against his fathers knees and covered his ears against the thundering onslaught.

Where was his mother? Harry, his five-year-old brother, was running on the tracks. Bernard, two and a half years old, was waddling off in another direction. David, the baby, was screaming in his carriage. Standing on the platform, holding tightly to the handle of the carriage, Al didnt know what to do. Should he leave David and run after his brothers? Should he try to push the carriage through the crowd? Adults, exhausted and confused, labored under bundles tied with string, lugged satchels, leather valises, and cardboard trunks, trying to find their place on platforms so long they seemed to lead to nowhere. None of these adults was his mother. He was paralyzed with fear.

Mama! he yelled. Where are you?

Mama! he cried. Come back!

It was chaos, Al remembers. It is a moment that is as clear to me today as it was then. I realized that I must not rely on this woman for my survival. I must not. Either we are all going to get killed, or those of us who stay alert are going to survive, because she doesnt know what shes doing. I realized that she was irresponsible. That I knew better than she did. I knew I could not put my life in her hands. I knew I was on my own. Suspended between two worlds, he understood that this was no time to look down. Al was six years old.

The year was 1927. At a time when Jews all over Europe were trying to get to the United States, Mildred Gordon Jaffee, homesick for zarasai, the Lithuanian shtetl from which shed emigrated, decided to leave Savannah and take her four American-born children back to an increasingly anti-Semitic Lithuania.

Mildred Jaffee told her husband, Morris, who had also emigrated from zarasai, that she was going for a brief visit to relatives, but she had probably never intended to return.

DOCUMENTS ARE INCONSISTENT about Morriss age when he first immigrated to New Yorks Lower East Side in 1905. He might have been as young as fifteen or as old as seventeen. He might have left Zarasai, as did many others, to keep from being conscripted into the czars army. (Lithuania would not become independent of Russia until 1918.) A 1910 census lists his profession as a tailor. It is unlikely that Morris had plans at the time to send for Mildred Gordon, whose age, also listed variously in different documents, would identify her as anywhere from three to seven years his junior. They might have known each other in zarasai, but their romance probably began in New York.

Morris Jaffee hit New York running. Al doesnt know what kind of work his father did in New York, but he was smart, well educated, buoyant, confident, and ambitious. Already fluent in Hebrew, Russian, and Yiddish, he enrolled in night school and quickly became proficient in English. Although Jaffee was a small, frail manno more than five feet four incheshis appetite for the challenges of the New World was immense. In a New York minute, he exchanged his black woolen cap for a dapper straw boater and set out to make this glitzy, noisy, crowded new world his own. He cheered for the Giants. He walked across the Brooklyn Bridge for the sheer joy of it. He had left a world lit only by kerosene, and nowhe could hardly believe ithe stood basking in the lights of the Great White Way. Whenever he could afford it, hed slip into the nickelodeon or the movies. His favorites were the Keystone Kops and Charlie Chaplin.

Mildred Gordon boarded the Czar in Libau, Russias largest emigration harbor, and arrived in New York on December 9, 1913. According to the ships manifest, which lists her name as Michlia Gordon, daughter of Chaim Gordon, she was a twenty-year-old, five-foot-tall Hebrew, a tailores with dark hair and eyes. She had twenty-two dollars in her pocket, the equivalent of almost five hundred dollars today. She listed her American destination as 305 Jackson Street, in the heart of the Lower East Side and the home of her cousin Morris Gordon.