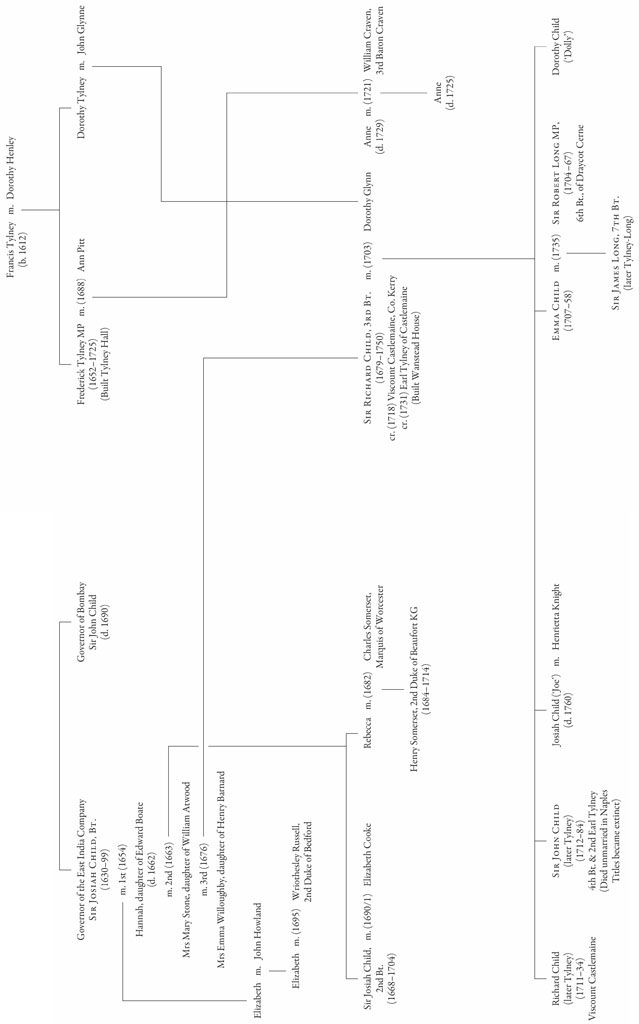

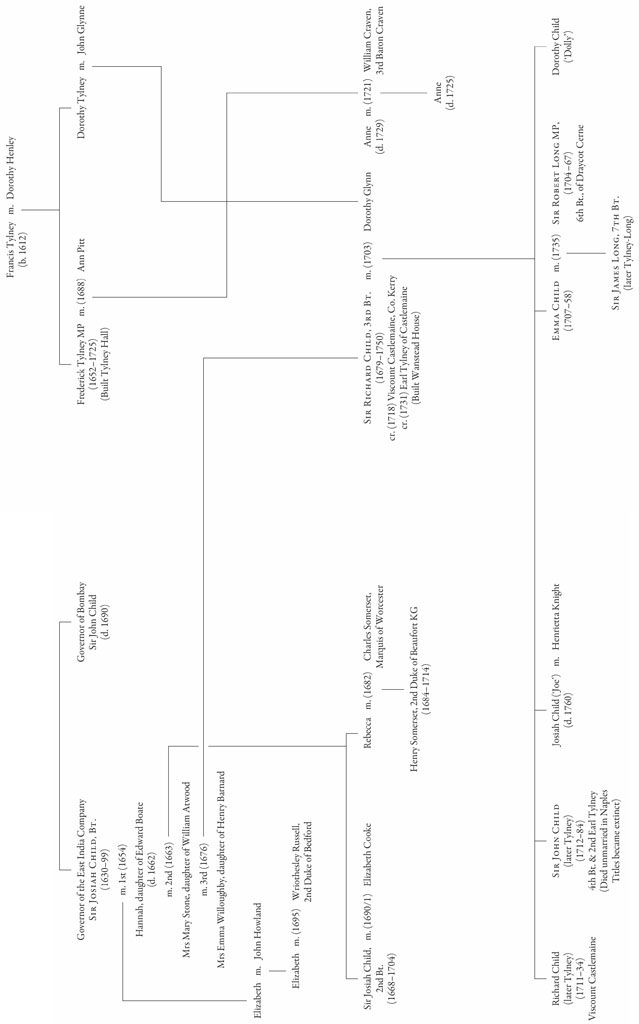

Catherines Family: Part 1

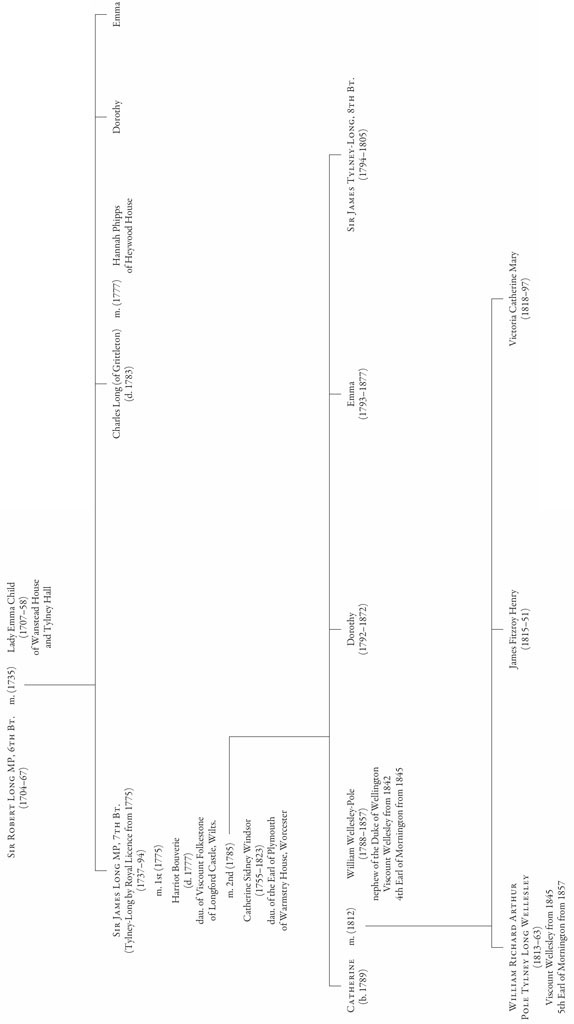

Catherines Family: Part 2

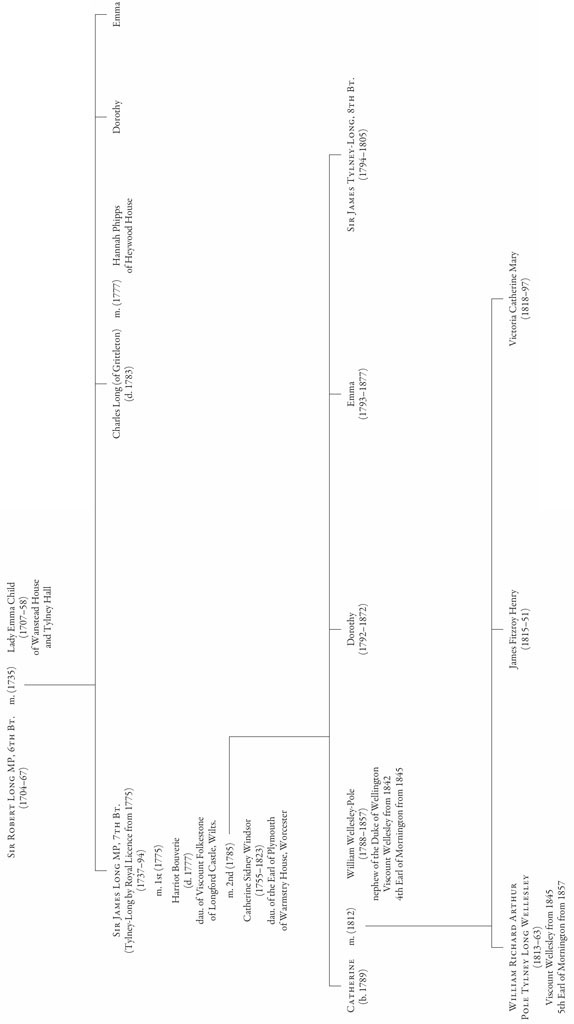

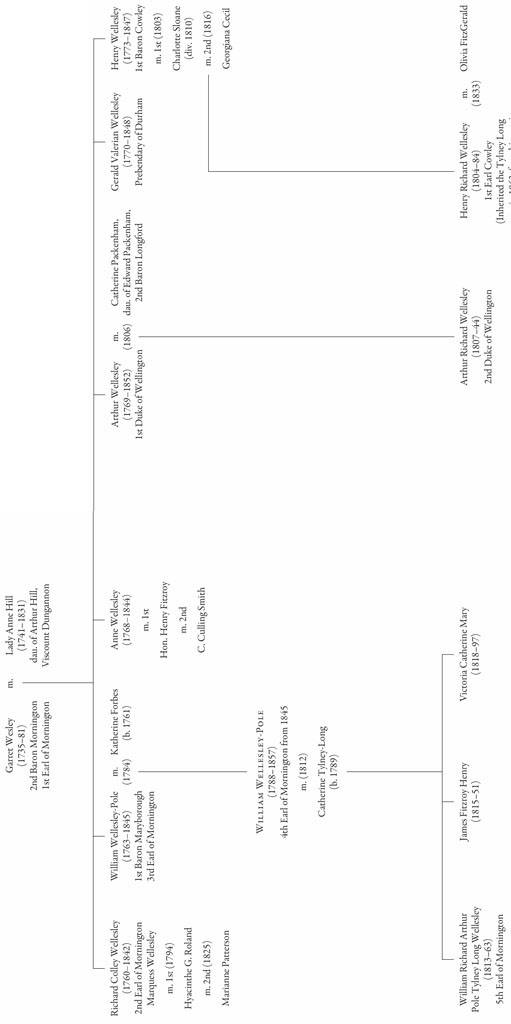

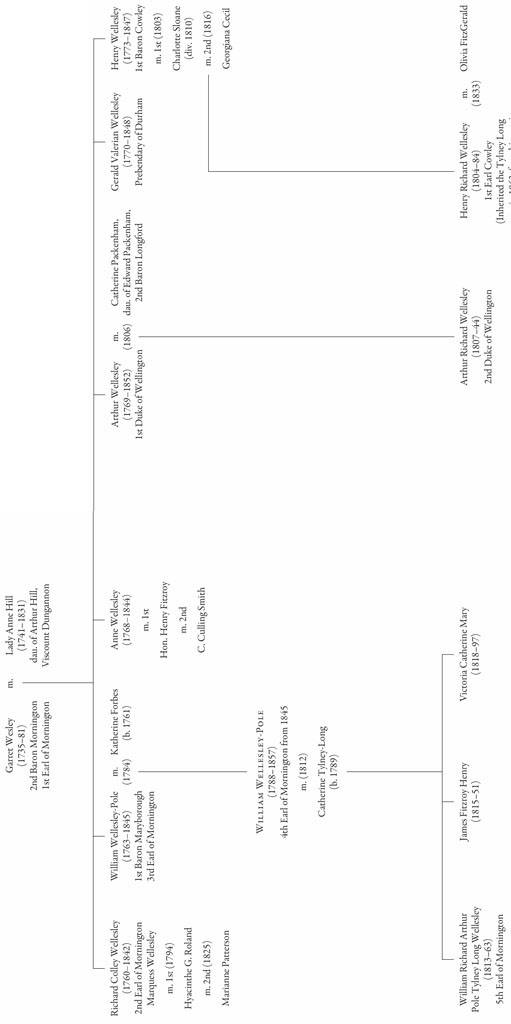

The Wellesley Family

List of Illustrations

Notes on the Text

The spelling of Catherines surname varies in newspapers, but has been standardized to the correct version, Tylney (as opposed to Tilney).

All quotations are cited in the references at the end of the book, but a few have been standardized and updated to modern English for the ease of understanding and clarity.

Money plays a huge part in Catherines story, but conversions over time are notoriously difficult. The Bank of England currency converter bases its calculations on average inflation of two per cent per year, estimating that 100 in 1810 is equivalent to around 7,000 in 2010 (i.e. multiply by 70). Very conservatively speaking, therefore, the Bank of England calculates that Catherines annual income of 40,000 would convert to around 2,500,000 today. This method is unreliable, however, because certain costs have soared disproportionately, such as house prices and rents. This is highlighted by the fact that in 1825, Catherines husband bought a detached villa in Hall Place (now Hall Gate), set in two acres adjoining Regents Park, for 6,000. Using the Bank of England converter, this villa would be worth around 320,000 in the early twenty-first century, when in reality a property like this would now fetch tens of millions of pounds. These soaring values must also factor into the equation, because Catherines assets were largely tied to land and property. So, in efffect, accurate monetary comparison is unfeasible and Catherine was far richer than the Bank of England conversion rates imply.

Throughout this book, I multiply by 100 to provide rough twenty-first-century equivalents. Even this, I believe, is conservative when calculating Catherines income.

Introduction

I first came across Catherine in a nineteenth-century newspaper, which summarized the remarkable twists and turns of her life. Eager to learn more, I scoured the Internet hoping to find a book or biography, but apart from a few sketchy outlines there was very little information about her. For some reason Catherine stayed with me, and I mentioned the article to my husband, telling him that it would make a terrific story for someone to write about. I am not usually superstitious, but it seemed like fate when I discovered a box of Catherines correspondence lying undocumented at Red-bridge Archives. I was immediately gripped by her letters, which are disarmingly candid and deeply moving. After reading through them I felt a compelling urge to tell her story.

In the main, Catherine has been portrayed as a feeble character. Kilverts diaries state that she was weak and foolish; letters to Lord Eldon suggest that she was dim and dull; while Octavia Barry repeatedly refers to her as sad... sorrowful... pathetic. This one-dimensional view has prevailed, even though all these previous publications were written in the nineteenth century, when it was considered proper for women to be acquiescent. Barry, in particular, endeavoured to portray Catherine in a sympathetic light by painting her as a saint, while deliberately avoiding all mention of the uproar she caused. When I began to scratch beneath the surface of this story, a very different image of Catherine emerged. Primary materials revealed that she was a vivacious, forthright, highly accomplished woman who painted landscapes, composed music and managed a huge household with efficiency. Her two most defining traits were her unwavering sweetness and courage.

Although Catherine wrote hundreds of letters during her lifetime, very few survive among her private papers at Redbridge Archives. Much of her correspondence was destroyed in a fire, which may have been started deliberately to protect her privacy. Owing to this, when I first started researching, there were huge gaps in my timeline, literally twenty years of Catherines life with no personal information to go on. The task of piecing together her story was daunting, but I was spurred on by my husband, Greg, who was researching a closely related subject. Over the subsequent ten years, our quest for clues extended to archives the length and breadth of Britain, from Southampton to Aberdeen, plus resources in Ireland and the USA.

My journey of discovery has focused on Catherine and her influence in Regency high society. I have been enthralled by the glamour and excitement of her life: the fashions and festivities, the scandal and gossip. As a popular celebrity, she was constantly in the news, which meant that contemporary newspapers provided much insight into the details of her life. The Hiram Stead Collection of Wanstead House material, held at Newham Heritage and Archives, has been an invaluable resource as it comprises a miscellany of newspaper and magazine clippings from a wide range of contemporary publications, some of which no longer exist elsewhere since sections of the British Library were bombed during World War II. Useful information was also gleaned from diaries, memoirs, fashion magazines and auction catalogues. But it has been particularly difficult to get to grips with finances due to the lack of primary source information. Much of the surviving fiscal documentation is riddled with inconsistencies, which means that the full picture cannot be definitively established.

The Angel and the Cad began its life as my MA dissertation, which explored the influence of newspapers in Regency England and the growth of celebrity culture. Newsmen of the day employed all kinds of literary devices to influence the public and capture their imagination. Reports about Catherine were filled with satire, tragedy and melodrama her life unfolded in the press rather like the chapters of a highly wrought novel. Owing to this, contemporary newspapers provided the perfect framework for this book, enabling the story to unfurl rather as it did at the time.

Although newspapers were rich in detail about events and occurrences, they did little to shed light on Catherines thoughts and feelings. In the early stages of my research, she remained a shadowy figure, compelling but elusive, and I needed to find primary source material that would flesh out her character. When my breakthrough eventually came, it was definitely worth the wait. Some years into her marriage, Catherine was embroiled in a scandal that resulted in a high-profile court case, which shocked the British public and resonated for many years. Discovering the trial transcript was a major step forward, particularly as the affidavits are so vividly descriptive. They include testimonies from many eye-witnesses, including the butler, tutor, close relatives and friends. Statements from the long-suffering valet are often comical, while accounts from the family physician are very powerful because he was Catherines confidante. Doctor Bulkeley observed many shocking scenes, and his descriptions are so graphic that I felt I was actually there watching the drama unfold.

I have been extremely fortunate to have had such wonderful material to work with. Regency gossip columns endeavoured to captivate the general public and their style of reporting remains accessible to a modern mainstream audience. In addition, the educated classes actively engaged in social networking, exchanging gossip through letters and notes. Letter writing was an art form and they rejoiced in the written word, entertaining friends with a droll turn of phrase or amusing anecdote. They delighted in the latest scandal, offering up snippets of gossip or describing acquaintances in acid detail. Extracts taken from letters, diaries and affidavits have greatly enriched this book, and I am indebted to the real-life characters that have added such colour and flavour.