PROLOGUE

Candles again.

At least this time her daughter was there to help. Martha Ballard had been making candles for over a decade, likely for most of her sixty-three years. She had probably repeated the hot, messy task each winter since she was a girl helping her own mother in Massachusetts. She was hardly unusual. Women all across the North Atlantic had, for generations, been slaughtering cows and trimming fat and guts from the carcasses. They had twisted wicks and boiled tallow. They had spent days and sometimes weeks every year dipping those wicks in the searing hot fat. Like their mothers and like their daughters, countless women had hung the dips until they hardened, then dipped again and again until the candles reached the proper size. For most of her adult life, Ballard had made nearly all of the lights consumed by her Maine household, and shed often had to do it alone. It was no small thing that someone had come to the house to share the work with her.

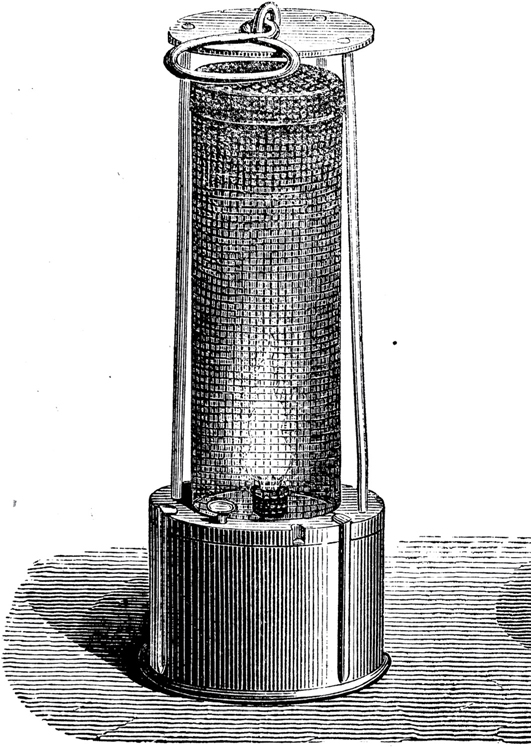

On February 21, 1797, Ballard recorded in her diary that her daughter Dolly Lambart Spun me yarn for Candle wicks. If Ballard, who was a midwife, hadnt been called away to deliver a child, the candle making would likely have begun that same evening. But the delivery took all night, and Ballard returned home only at nine the following snowy morning, undoubtedly exhausted. Worse, she knew she had no time for rest. Ballard willed herself through the fatigue, and on February 22, Dagt Lambart and I made 43 Dzn Candles. Ballard and Lambart began by twisting the spun cotton yarn into wicks, cutting them to the right length, and then doubling the wicks over specially made rods. While one of them stoked a fire under a kettle, the other cut in slices of the tallow from the cow killed in December until the kettle was full. When all the tallow was melted, they dipped the rods of wick-pairs into the boiling fatwhich had to be kept continually boiling for hoursset the dips to cool, and repeated the dipping over and over until they had 516 candles, each containing slightly less than an ounce of tallow. The process took hundreds of dippings and hours of continuous labor.

The work of candle making drew together not only mother and daughter, but the whole family. As Ballard noted, while they made candles, Lambarts husband Came and Sleeps here. And the work drew the whole family into a local community of energy joining sun to land to cow to flame to people. The wicks, spun by Ballards daughter from raw cotton likely grown by enslaved women and men on U.S. or West Indian plantations, drew further-flung connections. Most of the time, Ballard purchased, picked, carded, and spun the raw cotton into skeins herself. But neighbors often gave her their own spun cotton as payment for her midwife services. As for the tallow, a few months earlier, two of Ballards sons had helped extract the candle fuel when they Came and assisted us to Butcher a beef Cow. Beginning the slaughter at noon with her sons, Ballard had Cleand the Tripe & feet and Tried the Tallow by rendering the fat from all the other flesh and bone in a wood-fired kettle. Once the tallow was rendered, Ballard had Straind it to cool. I Closed my Evngs work at 11h 30m. The days labor required to fully unmake this cowafter, of course, raising and feeding it for a yearyielded enough fat to make ninety dozen candles.

It was tedious work. But it could also be dangerous. My Tallow Cought fire and alarmed us much, Ballard wrote after she and Lambart finished making the last of the candles. By then a seasoned hand, Ballard got the situation under control, putting out the flames and salvaging the remaining tallow. Lambart was not yet so capable. Panicked and breathing in smoke, my Dagt fainted by reason of her Surprise.

Unsurprisingly, rural women held candle making in a special kind of contempt. Writing over a century later, the Kansas settler Adelea Orpen recalled that besides dish washing, which she loathed, there was another domestic job which went very hard with methat was candle-making. Maybe it was because in my awkwardness I scalded my fingers in the boiling fat, or scratched them when putting in the wicks into the moulds. Anyhow I hated it, and let Auntie know the fact. Orpens story is a familiar one, marking history as a climb up from labor, a transcendence of work through new technologies of light. Orpens Auntie marked her own life in much the same way, telling her ungrateful niece how well she had it in the age of matches, when at least she didnt have to hike miles through the snow to borrow fire from a neighbor in order to light hearth and home.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, a similar, if differently gendered, narrative came to redefine lighting as a thing of progress, history, and pleasure, rather than work, routine, and pain. In 1891, a few decades before Adelea Orpen published her Memories of Old Emigrant Days in Kansas, Senator Orville Platt stood before the Congress of the United States and announced the electrical apotheosis of man. Formerly we ascribed creative faculty or force to the Divine Being alone, Platt noted modestly. But now when we look upon the wondrous contrivances and inventions everywhere contributing to our life wants and adding to our life enjoyments, we are forced to exclaim: Behold the expressed thought of the creatorman! Just in case his meaning was not clear enough, Platt assured his fellow legislators, If you will think as you come to this place this evening how the thought of man has transformed black coal and viewless electricity into the agents which light your pathway, you will feel it scarcely irreverent to exclaim: And man said, Let there be light, and there was light.