Michelangelo - Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo

Here you can read online Michelangelo - Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

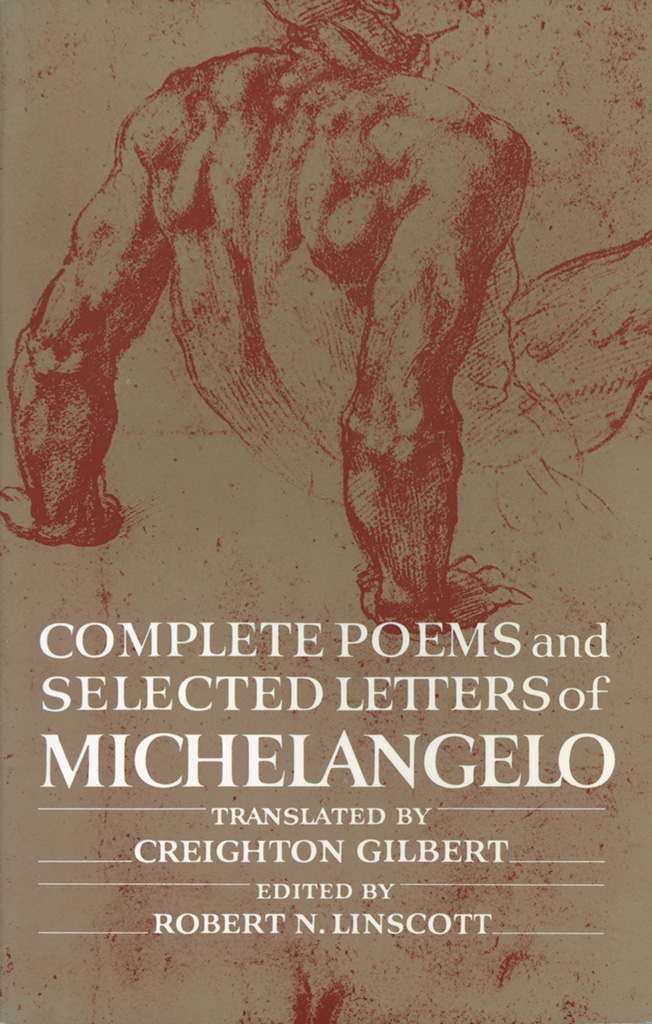

- Book:Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

AND SELECTED LETTERS OF

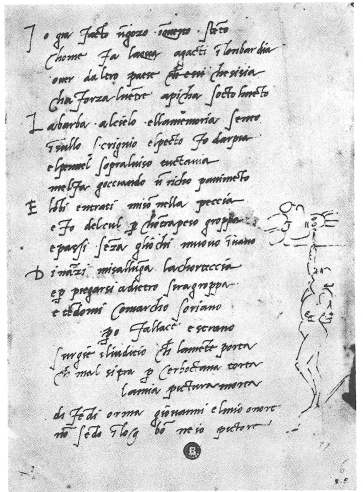

Manuscript page of the sonnet on the Sistine Chapel, 1510

COURTESY, ARCHIVIO BUONARROTI, FLORENCE

AND SELECTED LETTERS OF

TRANSLATED,

WITH FOREWORD AND NOTES

BY CREIGHTON GILBERT

BY ROBERT N. LINSCOTT

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1963 by Robert N. Linscott and Creighton Gilbert

Copyright 1980 by Creighton Gilbert

All Rights Reserved

LCC 79-87767

ISBN 0-691-07234-5

ISBN 0-691-02004-3 pbk.

eISBN 978-0-69122-177-9

First PRINCETON PAPERBACK printing, 1980

Originally published 1963 by Random House

Vintage Books edition, 1970

Acknowledgment is gratefully made to Yale University Press

for permission to reprint Creighton Gilberts

translation of two madrigals,

Lady, up to Your High and Shining Crown

and Led on through Many Years, which appeared in

Lyric Poetry of the Italian Renaissance,

edited by L. R. Lind.

Frontispiece:

Manuscript page of the sonnet on the Sistine Chapel, 1510

Archivio Buonarroti, Florence

The tiny sketch by Michelangelo on the right-hand side

illustrates the verse that describes his stance while painting

the ceiling. It is a self-portrait and also includes a head from

the ceiling, but briefly and sharply satirized in a way that

does not appear in any other drawing by him.

R0

ix

xi

xxvii

xlix

TO MAINTAIN the completeness of this book in presenting the poems, one additional fragment must be added. It consists of three lines which Michelangelo wrote beneath a drawing, one of his many tentative sketches for the design of the Medici tombs. The drawing includes a winged figure holding two horizontal rectangles. The three lines are:

Fame makes the epitaphs lie horizontal,

Because theyre dead, their action has been stopped,

It does not go forward, nor backward either.

Although this sheet and the lines have long been known to exist, there was a disagreement about whether or not they were verse. I was among those who thought they were prose, and so did not include them in this book. A re-examination of the way they are placed on the paper has shown that what seemed like one line of writing all the way across the paper, and therefore prose, was actually two lines, each eleven syllables long, the second a millimeter lower, and therefore verse. It has also changed an opinion which had been held by everyone, and has allowed us to arrange the lines in the order given above; previously, they were understood in the sequence which would be 1, 3, 2, in the order given above. That also made them incomprehensible. More details about this are in my article in The Art Quarterly, 1975.

Girardi, the editor of the standard edition of the poems in Italian, in chronological order, had regarded the lines as verse (in the old sequence), and printed them as poem number 11. The reader may therefore insert them after the tenth poem in this book.

CREIGHTON GILBERT

Cornell University

March 1979

THE OPPORTUNITY to correct errors of detail, which this new edition provides, is a privilege for which I am exceedingly grateful. No broad revisions have been undertaken, but the small fussy shifts involved here are more trouble in the issuing of a book than one is likely to think, and the less the reader notices them the more successful they are. In planning them, I have checked a number of new publications as well as reviews of the original edition (1963), and have been glad to make use of improved information and convincing guesses. In cases where I have not used changes proposed in the same publications, it may be generally understood that I was not convinced.

One change is large enough to warrant special mention. The standard edition of the letters in Italian was issued in 1875. The editor employed an assistant to copy the manuscript letters in the British Museum, most of which were from Michelangelo to his nephew. Michelangelo generally did not date these, and the editor suggested possible dates;

We can, to be sure, infer a good deal about Michelangelos personality from the letters, though the most facile inferences are not the most accurate. The long series of letters to his nephew browbeats the young man cruelly. The other letters are full of complaints and could make us think that Michelangelo was continually whining. Certainly he never ceased to complain of unfair treatment and of being cheated. From the letters alone we might be led to believe that Michelangelo was unbearably selfish. We can be rescued from this improbable idea of a short-sighted complacency by the poems. These show, with far greater acuteness, that he complained of his own shortcomings and failure with even more bitter rage. Putting these two observations together, we reach, I suggest, a meaningful deduction: all his life Michelangelo set before himself goals of achievement which were impossible. He applied these standards to everyone, first to himself, to his outrageously put-upon patrons, to his merely ordinary nephew. Never having experienced a failure of nerve that would lead him to admit compromise as the only plausible outcome of effort, he maintained the stress of his goals all his life. Perhaps this is what great men do. The fact that many of Michelangelos works are unfinished is clearly part of the same situation: it has been realized by many observers that he was discouraged by the failure of his own carving to match his original idea. (He was the first artist to leave unfinished works that appeal to modern aesthetic feelings as completely expressive forms, and his art is infinitely more personal than that of any other artist of his time.) The unfinished has often been discussed as a factor in Michelangelos art, but it has not perhaps been emphasized that it is at the heart of his expression.

The poems, then, reveal the private person whose public self we know in his sculpture and painting. Their role corresponds to that of other peoples letters. It was a social convention of Michelangelos time to write letters in verse, especially in the sonnet form, and especially by way of paying compliments. Michelangelos poems, like those of many other amateur poets of his time, were first produced this way. These early poems are few, and it may be that many others were not kept. Later, Michelangelo developed as a poet. Many are still addressed to his few closest friends, others to God, and in some he is evidently talking to himself.

The poems are difficult, for several reasons. One is that Michelangelo was an amateur writer and did not smooth things out. Some of these difficulties are impossible to resolve; for instance, antecedents are sometimes ambiguous. Other difficulties come from the shorthand presentation of very involved ideas; since readers of poetry today are used to that problem, the very long, prosy, and ultimately unsatisfying running expositions used by older editors are excluded here.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo»

Look at similar books to Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.