Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

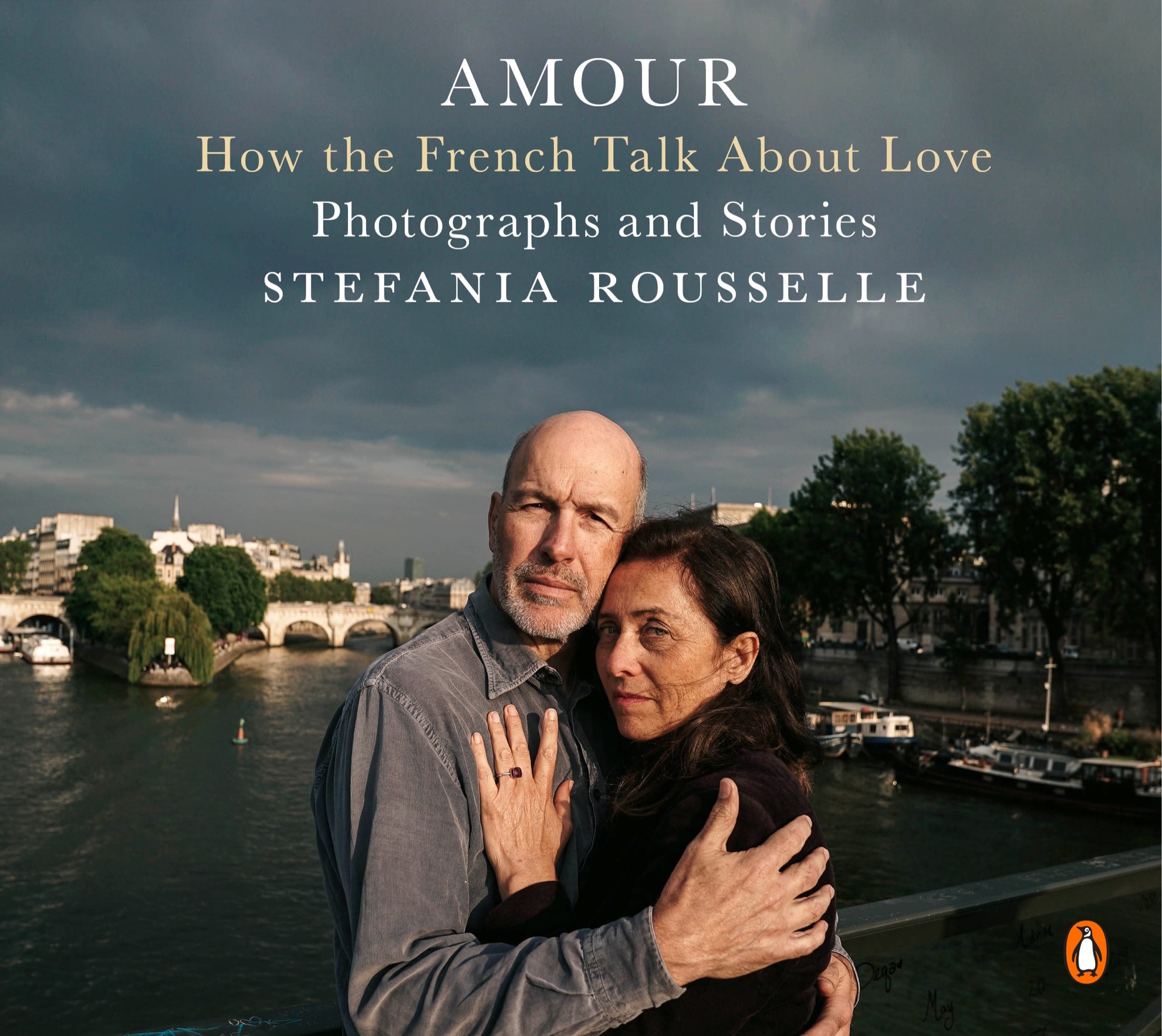

Names: Rousselle, Stefania, author.

Title: Amour : how the French talk about love--photographs and stories / Stefania Rousselle.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019024430 (print) | LCCN 2019024431 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143134534 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525506324 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Love--Public opinion. | Public opinion--France.

Classification: LCC BF575.L8 R688 2020 (print) | LCC BF575.L8 (ebook) | DDC 177/.7--dc23

I NTRODUCTION

It was Friday night. I was at home, in my pjs, on my couch, watching a documentary, Reporters, by Raymond Depardon. But then an alert popped up on my phone: Hostages taken at the Bataclan in Paris. In a second, I was out in the street. And I saw it: the fear, the police, the ambulances.

It was November 13, 2015. A massacre was taking place right down my street at the Bataclan concert hall. Terrorists were blowing themselves up and shooting people all over Paris.

I ran back up to my apartment, grabbed my camera gear, and started recording.

My editor at the New York Times called.

Are you on it?

Yes.

I hadnt even had time to change out of my pjs.

I had been working as a freelance video journalist for the New York Times for the past five years. I covered sex slavery in Spain. The European debt crisis and families despair. Pain and sadness. I also covered fashion in Paris, Milan, and London. Trauma versus glitter. Always on deadline. Always working in a rush. Film, edit, leave. Film, edit, leave. Pain, sadness, despair, repeat.

Back at home, I needed comfort. But I would never get it: What you did is not enough, my partner would say. I was never good enough. Ever. He injected his poison. Constantly. And I let it in; I was too in love with him. When I was at my lowest, he left me. His job was done. I was dead inside.

But I had to focus. I had work to do. I didnt want to let anyone down. I am strong. I could do this. Go Stefania, go. Work.

But then the Paris attacks happened. That terrible night in November 2015. 130 dead and 413 wounded. A man I knew died at the concert hall. I remembered dancing with him that very summer at a friends wedding. But he was gone now. Shot by a terrorist. The sadness overwhelmed me.

For weeks, whenever I heard sirens in the middle of the night, I would jump out of bed and start packing my camera gear, thinking I needed to go out and report. I couldnt stop. I had to work. I am strong.

The stories kept piling up. I embedded with Frances far-right partythe National Front. The party was very close to winning the regional elections, and I was there to witness it. Cover the hate. The racism. More poison. But I couldnt blink; I was a journalist.

Truth is, I was broken. I was suffocating. My heart was crushed. I had stopped believing in love. I wanted to die.

I would stay in the dark. In my room. For months.

But I decided to give myself one last chance. Because deep inside of me, there was hope. I told myself that I was going to go look for this so-called love. I was going to see for myself if people really cared for each other. Or if love was just a lie.

So I got in my car and hit the road.

I had no idea where to start. Then I thought of my grandmother, Maria, who was born in Hungary. Her stepfather ran a hospital there. Toward the end of World War II, the Soviet Army invaded her country and killed everyone in its way. She had to escape. Her family finally found refuge in a garage close to Nuremberg. But they had nothing, and her grandmother starved to death so everyone else could eat. But they were still hungry, so my grandmother was sent to get provisions. She went to the American base. And there was Henry, my grandfather, an intelligence officer with the Office of Strategic Services. They fell in love. Before long, my mother was born.

The north of France. Thats where I was going to head. To the refugee camps in Calais. But when I got there, nothing was left of them. The president had decided to tear them down to stop migrants from settling. So they had to hide in the woods. Sleep in the mud. Hoping to reach the United Kingdom. I arrived on a day when the police refused to let nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) do their lunch distribution. Not even water. I remember hundreds of hungry people, with loads of food right in front of them. Not being able to touch it. A few hours later, the police finally allowed the NGOs to serve dinner. Refugees crawled out of the forest like zombies and got in line. I walked up to Salam Salar, a thirty-one-year-old man from Pakistan. I told him about my grandmother and the journey I was starting in search of love. What he said boggled me: Love is my mother. Love is in trees and flowers. Love is good. I have a wife and four children, but they werent able to come to France with me. I miss them. He was seeing love around him, even in the worst conditions possible.

I didnt have a plan. No structure. No meetings. No agenda. I just wanted to wander. Get lost. Reconnect with people. The same day I met Salam, I sat down with Edith, a fifty-four-year-old accountant, in her impeccable white house in Sangatte, near Calais. She sighed: I am in love with the idea of love. I think it is a noble feeling. But when will I actually feel it? I have been with a man for a couple of years now, and I break up with him every day. But then, every night, he comes back. I am too much of a coward to leave him. I am so scared of solitude. It was brutal. People were pure. They were raw. There was no pathos. No bullshit. I remember Marcel, a sixty-three-year-old shepherd I met in the Pyrenees. We got so drunk together. When I told the people in the village I was going to look for him up in the valley, they all told me: Get some pastis, a delicious anise-flavored liqueur. And I did. I poured it into a plastic bottle so it wouldnt be heavy in my backpack and hiked up to find him. And when I did, we shared the bottle. He had named his cabin the Villa of Those Deprived of Love because he was the least favorite child in his family. When he started talking about his wife, Katia, there was no romanticism. Do I love her? I dont know. Love is a weird word. I care about Katia. That must be love. She cares about me tooa bit too much.

Marie-Elisabeth. Pierre. Andre. Annick. Michel. Claire. Patrick. For each beautiful and consoling moment, there was one of abandonment. Of loss or rejection. Of despair. Like Lucien, an eighty-two-year-old retired mason, whom I met in a little town in the southwest of France. His wife, Marie-Jeanne, had just died: In the winter, we would watch television, then sit near the fire and fall asleep in our respective chairs. We were happy. I always hoped it would last forever. It didnt.