Contents

Guide

Page List

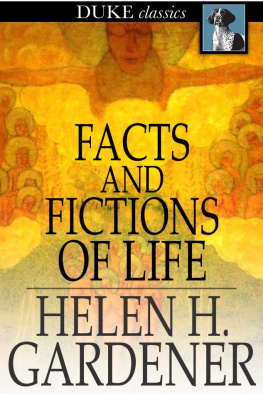

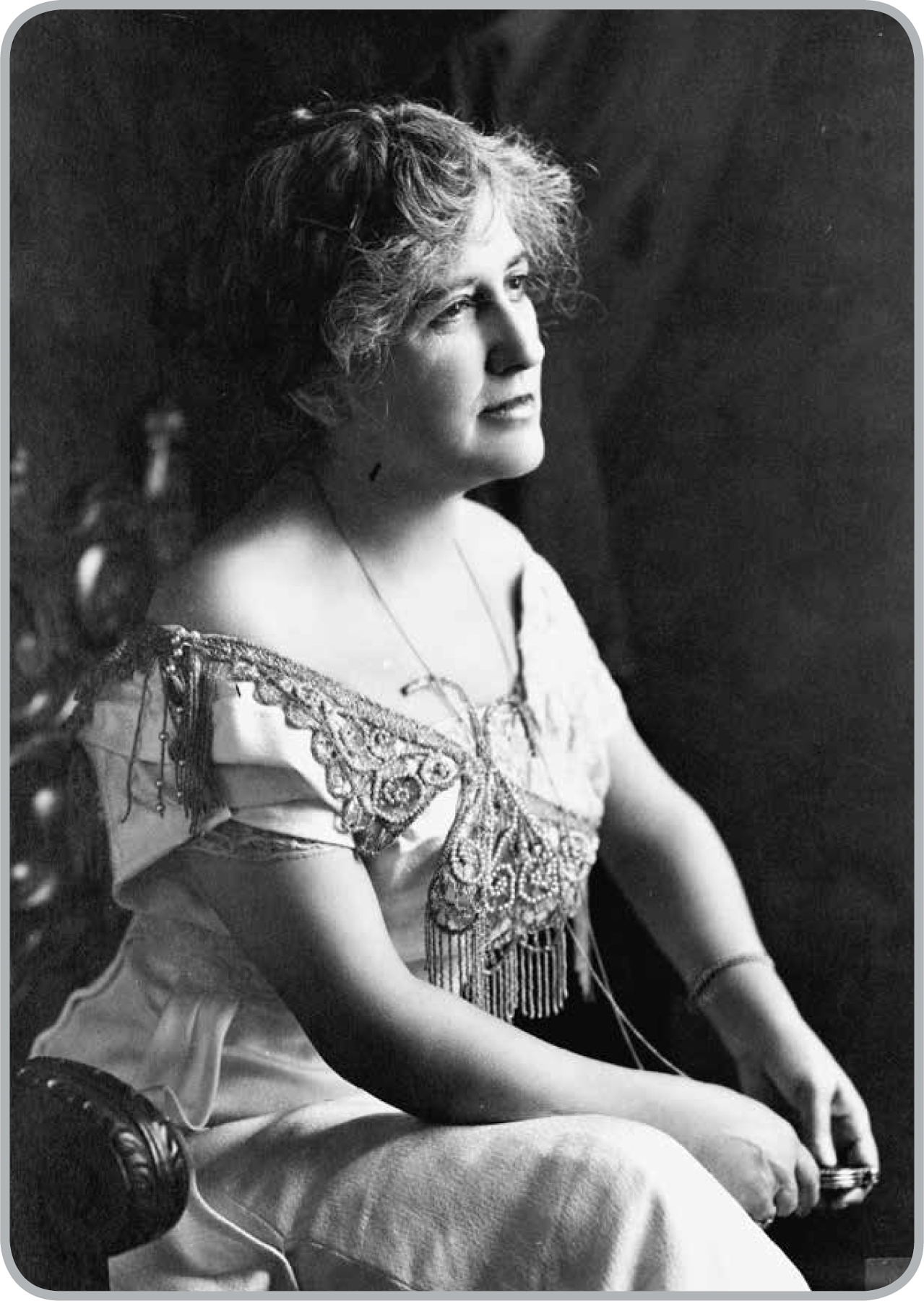

Helen Hamilton Gardener, 1913, just as she found her calling as the suffragists Diplomatic Corps in Washington, D.C.

FREE THINKER

SEX, SUFFRAGE, AND THE

EXTRAORDINARY LIFE

of

HELEN HAMILTON GARDENER

KIMBERLY A. HAMLIN

To Ruby and Elias

Contents

O N JUNE 4, 1919, the U.S. Senate followed the House in passing the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. After three generations of activism, this amendment removed sex as a legal basis for denying citizens the right to vote. One triumphant woman rushed to attend the signing ceremony. And why not? She had planned itdown to purchasing the fancy gold pen the vice president and the Speaker of the House would use to endorse the amendment before sending it off to the states for ratification. She took her deserved place beside both men as they signed. Flash bulbs captured her standing proud, and her image graced the front pages of newspapers across the nation. Days later, she arranged for the Smithsonian Institution to display the first-ever exhibition on the long history of the suffrage movement. Within the year, she had become the highest-ranking and highest-paid woman in federal government: the personification of what it meant, finally, for women to be full citizens. Her nameat the timewas Helen Hamilton Gardener, and she was famous.

She was also transgressive and bold and a very unlikely woman to become the public face of female citizenship. Though hardly anyone knew itcertainly not her suffrage colleaguesGardener was a fallen woman. In her early twenties, when she was working as a school principal in Sandusky, Ohio, she had an affair with a prominent elected official who also happened to be a married father of two. As a result, she lost her hard-earned job and her reputation. Rather than accept her fate as a fallen woman and recede quietly into the shadows, she determined to figure out why chastity was considered a womans most valuable asset and why men were held to such different standards when it came to sex. Then she turned her findings into a lifetime of feminist reform.

Born when most women dared not speak in public and when few had a voice in public or private decisions, Gardener pioneered an independent life for herself. After her affair, she moved to a new city and changed her name from Mary Alice Chenoweth to Helen Hamilton Gardener. She did not marry until she was almost fifty. And, significantly, she was neither a mother nor a spinster. Vivacious and charismatic, Gardener loved to entertain but hated to cook. Though she lacked a steady income until her late sixties, she prided herself on her stylish clothes and elegant tastes. She tolerated the two men she lived with as husbands, endured their many foibles, and reserved her strongest emotional attachments for her female friends, especially Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Gardeners early sex scandal and ongoing romantic struggles opened her eyes to the links between womens sexual, financial, and political autonomy. Her lifes goal was to secure all three. To convince her peers that women were self-respecting, self-directing human units with brains and bodies sacredly their own, she realized that she had to challenge the foundational stories about women inscribed in the Bible, science, fiction, and the law. So she rewrote those, too. She became one of the most sought-after speakers on the nineteenth-century lecture circuit, published seven books and countless essays, supported herself, hobnobbed with the most interesting thinkers of her era, visited twenty-two countries, and was celebrated for her audacious ideas and keen wit. News reports often commented on the contrast between her tiny statureshe was barely 5 feet tall and weighed less than 100 poundsand her big ideas.

After charting an independent and unconventional life throughout the United States and abroad, Gardener settled in Washington, D.C., and joined the suffrage movement. In the 1910s, many suffragists deftly lobbied in Washington, but only one lived next door to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and only one became a welcome daily presence at the White House. Gardeners many successes in D.C. demonstrate that not only is the personal political, but so, too, is the political personal. Upon Gardeners death in 1925, suffrage leader Maud Wood Park described her friend as the most potent factor in securing congressional passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

In her eulogy, Catt also referred to Gardener as a great White soul, revealing the extent to which Gardeners story, and the larger story of the womens suffrage movement, is about race and, more to the point, whiteness. Even though she took great pride in her Virginia familys bold stance against slavery and intrepid service in the Union army, Gardener devoted the penultimate chapter of her life to securing the vote for white women, all the while knowing that black women in the South, along with other women of color, would not be enfranchised. For all her intellectual bravery and iconoclasm, she could not see her way through racism. Her life sheds new light on the racialand racistdynamics underscoring the womens suffrage movement and why it was not until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that the Nineteenth Amendment became a reality for all women.

Gardeners dying wish was that the George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamiltons of the womens rights movement would be studied by schoolchildren, commemorated in museums, and have their graves tended by citizens paying tribute to the women who devoted their lives to what she called the greatest bloodless revolution. In a curious twist, her brain remains on display at Cornell University, but hardly anyone has ever heard of Helen Hamilton Gardener or the countless other women who endured decades of scorn and unimaginable obstacles in their long campaign to attain the right to live as autonomous people.

A quintessentially American story of self-making, Gardeners life provides a window into another Americaa nation that women helped to make and the nation that women imagined America might become. This book is an invitation, an entreaty, to look for more Helen Hamilton Gardenersof all backgrounds, races, and ethnicitiesto learn from the worlds they hoped to create; to revise our national stories to celebrate their experiences and contributions; and to become familiar with their complexities, failures, and triumphs so that we might better understand our own.