Copyright 2020 by Bettye Kearse

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kearse, Bettye, author.

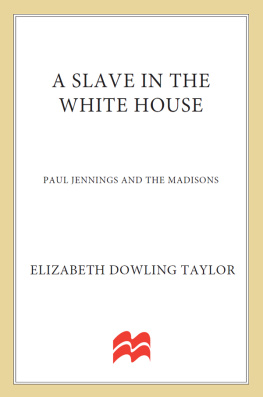

Title: The Other Madisons : the lost history of a presidents Black family / Bettye Kearse.

Other titles: Lost history of a presidents Black family

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019024941 (print) | LCCN 2019024942 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328604392 (hardback) | ISBN 9781328603531 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Madison, James, 17511836Family. | Madison, James, 17511836relations with African Americans. | Madison family. | Mandy, active 18th century. | Coreen, active 18th century. | African American familiesHistory. | Racially mixed peopleUnited States. | SlavesVirginiaHistory. | FreedmenTexasHistory.

Classification: LCC E342.1 .K43 2020 (print) |LCC E342.1 (ebook) | DDC 973.5/10922dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024941

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024942

The chapter entitled Destination Jim Crow was first published under the same title, in different form, in the Fall 2013 issue of River Teeth Journal. Reprinted by permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Image credits appear on .

Cover design by Christopher Moisan

Cover photographs courtesy of the author and her family Shutterstock / Everett Historical (James Madison); Parrot Ivan / Shutterstock (silhouette)

Author photograph Eduardo Montes-Bradley

eISBN 978-1-328-60353-1

v2.0320

To my mother, Ruby Laura Madison Wilson,

who taught me to value pride

To my father, Clay Morgan Wilson III,

who taught me to value humility

To my grandfather John Chester Madison,

who taught me to value a story well told

Madison Family Tree

Prologue

I am griot, master of eloquence, the vessel of speech, the memory of mankind. I speak no untruths. This is the word of my father and my fathers father. Listen to me, those who want to know. From my mouth you will hear the history of your ancestors.

West African griot opening chant

For thousands of years, West African griots (men) and griottes (women) have served as human links between past and present, speaking the ever-expanding stories of their ancestors and the history of their peopleaccounts of births and deaths, conquests and defeats, times of plenty and times of famine, vast empires and small villages, nobles and heroes and commoners. These men and women are not simply oral historians, genealogists, storytellers, and teachers; they are also spokespeople, exhorters, interpreters, judges, poets, musicians, and praise-singers. Their wisdom and their voices preserve not just a family or a community but an entire culture and its values.

In his book Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music, Thomas A. Hale writes, No other profession in any other part of the world is charged with such wide-ranging and intimate involvement in the lives of people. These wordsmiths, he continues, are the social glue of society. Their words and the layers of meaning behind those words influence how each person views himself in the present and on the continuum of past and future. In the eyes of West Africans, griots and griottes are fundamentally different from other human beings. Even their burial rituals are unique. Though neither religious icons nor sorcerers, they hold an aura of power and mystery that makes them at once frightening and revered.

American slave owners successfully abolished many African customs, but the tradition of oral history has held strong. For many African-American families, including mine, this tradition is all that preserves the legacies our ancestors left for us. In the official history of America, their stories were excluded, ignored, marginalized, or distorted. But in each generation of my family, the griot has kept the stories alive and added his or her own important lessons and personal tales to the saga in order to leave evidence that they, like their predecessors, existed and, though often confronted by restrictive circumstances, did all they could to make the most of their lives.

Our first wordsmith was a slave called Mandy. When it came time for me to take on the role, she and our familys other griots, living and dead, helped me to discover and add my own lessons and personal tales. Their words encouraged me to write down their legacies and include my own for the coming generations. But it was Mandy who held me up when I doubted I could become the griotte. Sometimes I felt so close to her I could hear her voice. It was like a xylophone: precise, clear, musical. The melodys lilt slid down at the end of each sentence, the consonants percussive, the vowels softthe inflections of the Ga language of Ghana.

Mandy

When I was a girl, I didnt know people stole people. I used to sneak away from my village and go to the edge of the ocean, my ocean. I was very young and a little foolish then. I thought that huge body of water belonged to me. A big, knotty tree with twisted branches stood alone on a hill, where it watched over my village on one side and the water on the other. My favorite spot was a cove hidden among tall boulders. I went there whenever I could. All kinds of reptiles, insects, and sea plants clung to rocks, slipped into cracks, or hid in shadows to get away from the sun and wind pounding the beach. Sometimes, I took the small creatures home, but usually, I left them where they were so theyd be there whenever I came back.

Even if I was supposed to be tending chickens, cooking, or watching my brother, Id sneak down to the water. Sometimes I could only stay a minute, but sometimes I stayed for hours, digging my toes deep into the cool sand. Warm sea wind brushed my cheeks while twinkling blue water hurried to the shore and curled into white, foamy ringlets that pulled the sand toward the bottom of the ocean. When the sand drew away with the water, I dug my toes in further, because I could feel it tugging my feet, trying to take me with it too. But I thought I was going to stay on that land forever. I grabbed the sand with my toes like they were the roots of a tree, and I stayed right there. Funny how my little toes were stronger than that whole big ocean. I didnt move but a tiny bit.

In the mornings, the sun was hot on my shoulders. In the afternoons, it was my forehead and chest that tingled in the heat. Sun shining down on my body, I watched the water get higher or lower, so slow I couldnt see it changing. Bubbly water hid thin strips of sand, but if I kept watching, shellfish I hadnt seen moments before scurried across the shore, trying to keep up with the ocean and leaving behind smooth and shiny pink or silver or green or blue or rainbow-speckled pebbles.

The biggest part of the ocean, the part that touched the far-away sky, had too-many-to-count white peaks that grew smaller and smaller in the distance. In the coves, the water calmed into soft ripples, like ribs rising and falling in regular breaths. On the open beach, frisky waves ran up to the bank, hit the rocks, then splashed into white sprays, just like they were playing. Any movement or sound in one part of the ocean swelled up or hushed down in another.