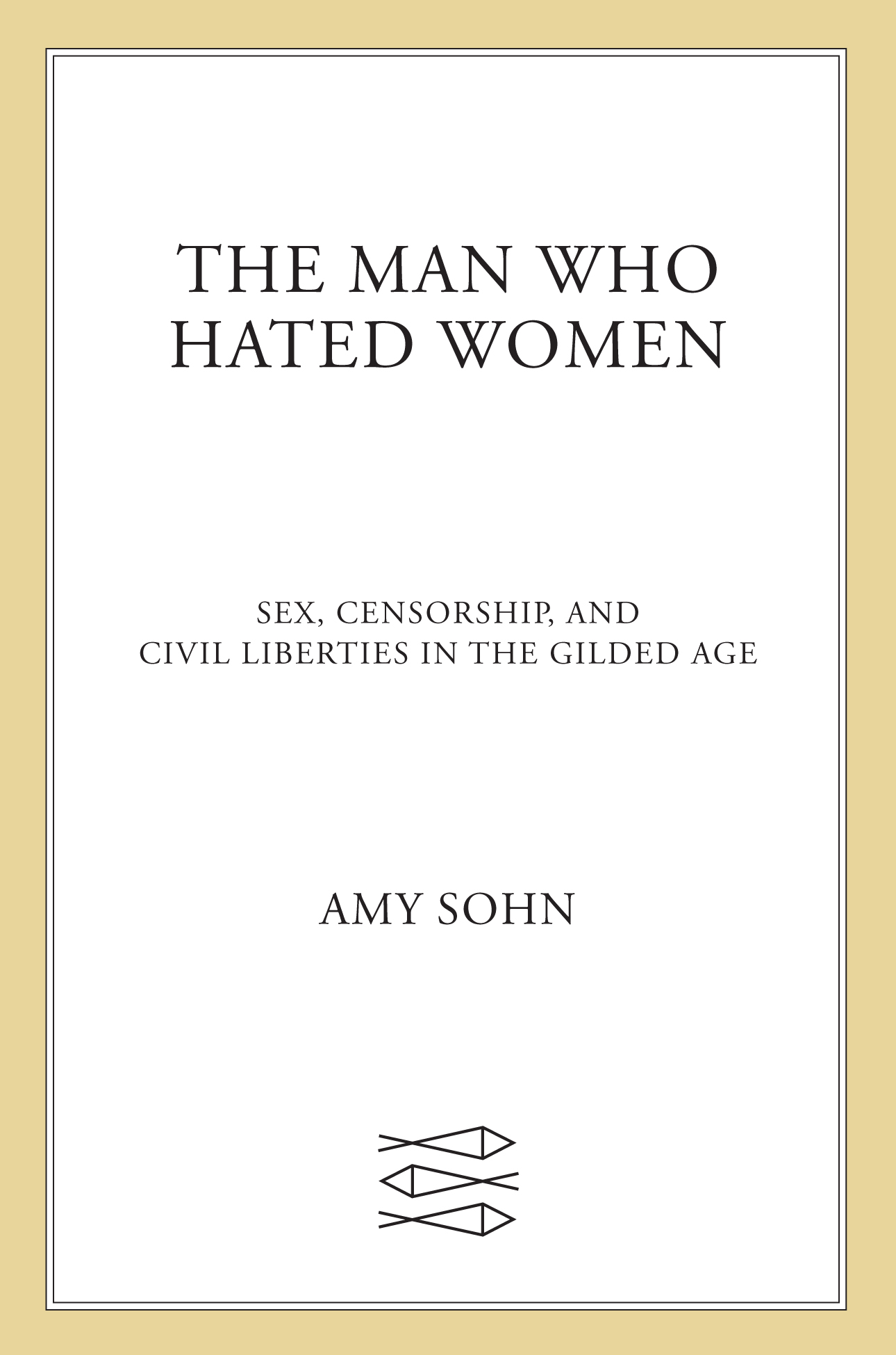

Amy Sohn - The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age

Here you can read online Amy Sohn - The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2021, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- City:New York

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The New York Times-bestselling author Amy Sohn presents a narrative history of Anthony Comstock, anti-vice activist and U.S. Postal Inspector, and the remarkable women who opposed his war on womens rights at the turn of the twentieth century

Anthony Comstock, special agent to the U.S. Post Office, was one of the most important men in the lives of nineteenth-century women. His eponymous law, passed in 1873, penalized the mailing of contraception and obscenity with long sentences and steep fines. The word Comstockery came to connote repression and prudery. Between 1873 and Comstocks death in 1915, eight remarkable women were charged with violating state and federal Comstock laws. These sex radicals supported contraception, sexual education, gender equality, and womens right to pleasure. They took on the fearsome censor in explicit, personal writing, seeking to redefine work, family, marriage, and love for a bold new era. In The Man Who Hated Women, Amy Sohn tells the overlooked story of their valiant attempts to fight Comstock in court and in the press. They were publishers, writers, and doctors, and they included the first woman presidential candidate, Victoria C. Woodhull; the virgin sexologist Ida C. Craddock; and the anarchist Emma Goldman. In their willingness to oppose a monomaniac who viewed reproductive rights as a threat to the American family, the sex radicals paved the way for second-wave feminism. Risking imprisonment and death, they redefined birth control access as a civil liberty. The Man Who Hated Women brings these womens stories to vivid life, recounting their personal and romantic travails alongside their political battles. Without them, there would be no Pill, no Planned Parenthood, no Roe v. Wade. This is the forgotten history of the women who waged war to control their bodies.Amy Sohn: author's other books

Who wrote The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.