Annotation

**The *New York Times* -bestselling author Amy Sohn presents a narrative history of Anthony Comstock, anti-vice activist and U.S. Postal Inspector, and the remarkable women who opposed his war on women's rights at the turn of the twentieth century** Anthony Comstock, special agent to the Post Office, was one of the most important men in the lives of nineteenth-century women. His eponymous law, passed in 1873, penalized the mailing of contraception and obscenity with harsh sentences and steep fines; his name was soon equated with repression and prudery. Between 1873 and the ratification of the nineteenth amendment in 1920, eight remarkable women were tried under the Comstock Law. These "sex radicals" supported contraception, sexual education, gender equality, and a woman's right to sexual pleasure. They took on Comstock in explicit, bold, personal writing, seeking to redefine work, family, sex, and love for a new era. *The Man Who Hated Women* tells the...

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

A Note About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

For my grandmother Bess Rosenfeld Katz

Comstock is dead, but there are women dying everywhere.

Ida, tell me again how much we cannot speak of.

Oh, these Gods and Masters!

from JULIANNA BAGGOTT, Margaret Sanger Addresses the Ghost of Ida Craddock

List of Illustrations

Dancer from Cairo Street: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-093962A.

Ida C. Craddock: Ida Craddock Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Cartoon depicting Victoria C. Woodhulls nomination for president at Apollo Hall, May 1872: M. F. Darwin,

One Moral Standard for All: Extracts from the Lives of Victoria Claflin Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin

(Caulon Press, n.d.).

Angela T. Heywood: University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center, Joseph A. Labadie Collection).

Ezra Heywood: University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center, Joseph A. Labadie Collection).

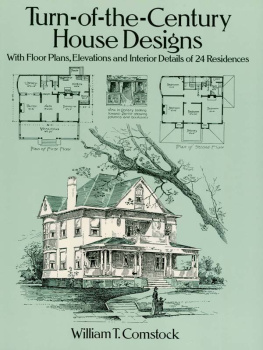

Mountain Home circa 1872: Princeton Historical Society, Princeton, MA.

Ida C. Craddock: Ida Craddock Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Ida C. Craddocks business card: Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-65509 (front); Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-65508 (back).

Clarence Darrow: U-M Library Digital Collections. Labadie Photograph Collection, University of Michigan.

Anthony Comstock in his New York office: Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-4495.

Emma Goldman: International Institute for Social History, Amsterdam, IISG BG A5/483.

Ben Reitman: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-12108.

William Sanger: Alexander Sanger on behalf of estate of William Sanger.

The Masses

magazine cartoon by Robert Minor, September 1915: Marxists International Archive and Riazanov Library Digital Archive Project.

The Sanger Clinic:

New York World-Telegram

and

The Sun

Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62138888.

Margaret Sanger, 1916: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-20859.

Dancer from Cairo Street

THE DANSE DU VENTRE

It was the summer of 1893, and Ida C. Craddock was in the Cairo Street Theatre at the Chicago Worlds Fair, watching the belly dancers. There were about twelve of them, all in their late teens to early twenties, and as each one performed, the others sat behind her on divans to watch. Musicians played drums, woodwinds, and strings. The Algerian and Egyptian dancers wore ornamented headdresses, tiny cymbals on their fingers, knee-length peasant skirts, fringed epaulets, hip belts with vertical fabric flaps, and long beaded necklaces. Black stockings covered their legs. They had white muslin drawers to the knees, and high-heeled slippers. Their skirts waistbands, shaped like coiled snakes, rose only to their hips, and their netted silk undervests were semitransparent. Spectators could see their navelsas shocking as a camel ride, another attraction at the Worlds Fair. American women were never seen in public without corsets, much less with their abdomens exposed. Victorian-era dances were led by dancing masters, who directed steps and patternsno improvisation or gyrations.

The dancers moved their bellies coyly, clicking cymbals and swaying the upper part of their bodies. Some held bottles of water on their heads. Their gyrations grew more agitated and spasmodic as they rang their cymbals faster. Very few made direct eye contact with male audience members. When the performances reached a climax, the women would stand stock still, as if seized by something violent, and then visibly grow exhausted.

Viewers took in the belly dance with bemusement, horror, and titillation. Some cried out Disgusting! and fled the theater. Some men who stayed had looks on their faces that, as Craddock put it, they would have been ashamed to have their mothers or their girl sisters see. To her, those people were philistines.

She was a thirty-six-year-old teacher with brilliant blue eyes; her complexion was clear, her features cameo-cut, and her fingers delicate and tapering. She was living in her domineering mothers Philadelphia living room behind a partition she called the cubicle.

After having tried and failed to be the first woman admitted to the University of Pennsylvanias liberal arts program, she had become a lay scholar of comparative religion, reading voraciously at Philadelphias Ridgway Library. She was at work on two manuscripts, one on the origin of the devil, and one on sex worship, or sexual symbols in ancient world religions. She taught stenography at Girard College, a school for orphaned boys. By the time of her Worlds Fair visit, she had taught herself, and written a book on, a form of shorthand, which she believed could help ambitious men and women work their way up in business.

In the danse du ventre, Craddock saw a visual fusion of her two passions: sex and symbolism. While a teenager at Philadelphias prestigious Friends Central School, founded by Quakers, a lesson on botany ignited her curiosity about sex. As she recalled in a short memoir titled Story of My Life: In Regard to Sex and Occult Teaching, the instructor, Annie Shoemaker, told the class, Girls, whenever I take up this subject, I feel as though I were entering a holy temple. As Craddock learned how plants were fertilized, she felt all on fire with the delight of my discovery, intellectually keen and eager From that hour, dates the birth of my idealizing of sex.

In Chicago, twenty years after that lesson, she understood that the belly dancers thrusts were simulating a womans movements during intercourse. The bottle of water was an erect penis on the verge of ejaculation. And the extreme self-control was a reference to male continence, or coitus reservatus , a better-sex and contraceptive technique in which a man orgasms without ejaculating. When three women behind her at the show made sarcastic comments, she turned and said, If you knew what that dance signifies, you would not make yourselves conspicuous by laughing at it. She believed it was a religious memorial of purity descending from ancient days. To serve God was not to choose asceticism but to experience self-controlled pleasure. After a gentleman overheard Craddocks rebuke, he was so impressed he vowed to return with his wife. This was the highest compliment she could be paid: he had been listening, he had taken her words seriously, and he was coming back.

Next page