Table of Contents

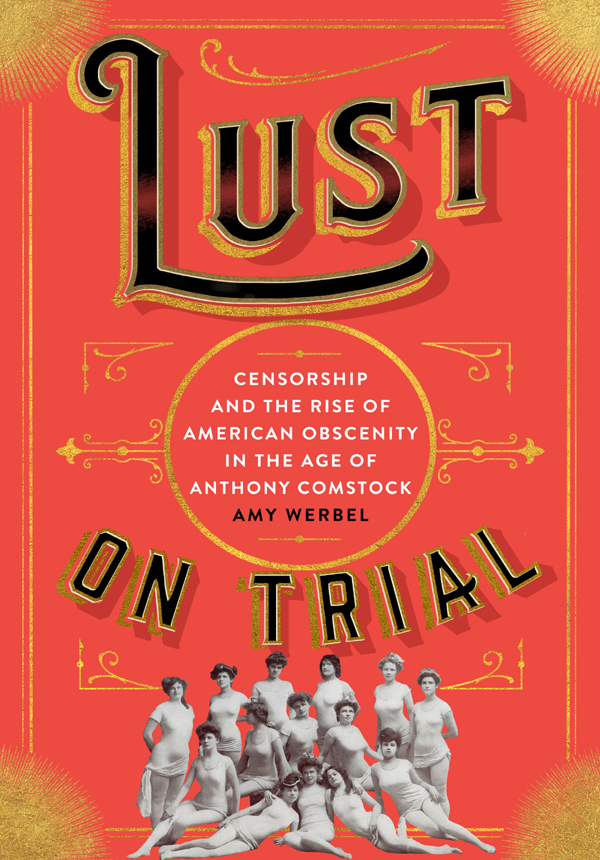

LUST ON TRIAL

LUST

ON TRIAL

CENSORSHIP AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN OBSCENITY IN THE AGE OF ANTHONY COMSTOCK

AMY WERBEL

COLUMBIA

UNIVERSITY

PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54703-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Werbel, Amy Beth, author.

Title: Lust on trial: censorship and the rise of American obscenity in the age of Anthony Comstock / Amy Werbel.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017042441 (print) | LCCN 2017049977 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231547031 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231175227 (cloth: alk paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Comstock, Anthony, 1844-1915. | New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. | CensorshipUnited StatesHistory. | Obscenity (Law)United StatesHistory. | United StatesMoral conditions.

Classification: LCC HV6705 (e-book) | LCC HV6705 W47 2018 (print) | DDC 306.77/1097309034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017042441

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Philip Pascuzzo

Cover image: Bernarr Macfaddens Womens Physical Culture Competition, 1903. Photograph. H. J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture & Sport. The University of Texas, Austin.

For the Defense

CONTENTS

FIGURES

PLATES

I n 1888, a great scandal burst onto the front page of New York newspapers. A young man named La Grange Brown had taken photographs of nude young women in his parents posh home at 100 Hicks Street in Brooklyn Heights. The Heights was prized then as now not only for its stately homes and elegant churches, but also especially for its spectacular views of Manhattan, just across the East River. News coverage of the story was profuse. The New York World reported that police had taken Brown into custody, along with 239 negatives and 520 pictures that are the counterfeit presentment of women and young girls in the giddy garb of Nature, and it is whispered that some of the females who have had their charms focused by young Brown are the daughters of highly respectable families.

The discovery of Browns enterprise was not the result of intrepid police work but instead stemmed from a tip from Anthony Comstock, Inspector for the United States Post Office Department and Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). A few days before the raid, a gentleman visited Comstocks office and told him that while he was waiting for a prescription at the saloon of Valentine Schmitt in Brooklyn the evening before, a young man had exhibited to a throng of people there obscene pictures of nude females. When Comstock and two police officers went to find Brown, they discovered him drunk in Schmitts saloon. Upon being apprehended, Brown warned Comstock and the officers that he had wired his studio to electrocute any attempted interlopers. Undoubtedly skeptical of Browns drunken boast, the three men carried him back to his house, where they unfortunately discovered that he had not lied.

When a detective opened the door to the laboratory, he received a shock from a current of electricity. Inside the secretive lair, Brown was found to have all the latest appliances, including instruments used by microscopists, and plates and photographs from life, and several were evidently taken by a flash light, instantaneous process worked with an electrical or clock-work appliance, for the subject of them was Brown himself with a nude or partly nude female on his knee. Some of the women had modesty enough that they hid their faces with their hands or arms, and others turned their faces away from the camera. When Comstock grilled Brown as to the subjects of the pictures, he backed off his claim that they were respectable local women and instead insisted that they were naturally women of loose morals; the majority of them women who have passed beyond the pale of society.

The evidence we have today of what actually happened in Brooklyn Heights is scant, but the episode nevertheless is illuminating about the state of production, distribution, and suppression of photographs of nudes at the height of Anthony Comstocks career as a professional censor. First, we may note that Browns paranoia about the possibility of arrest was extreme but not unwarranted. By 1888, New Yorkers were well aware that the penalties for breaking obscenity laws were harsh. They also knew Anthony Comstocks name and the address of the NYSSV, where they could report items they found offensive, such as Browns photographs. Witness fees, set at a percentage of the penalties assessed, served as incentive for individuals to come forward.

As in most of the legal proceedings in which Comstock was involved, the Brown case raised important issues of class and social standing. Were they already loose, or had Brown damaged the good reputations of respectable women? All of this seemed to make a big difference in how the story was told and its meaning. Reporters of course were fascinated by the idea of girls in the giddy garb of Nature. They also enthusiastically reported on all the new technologies in Browns home, including his amateur electrified security system, flash lighting, and microscopists equipment. This was an age filled with innovations, and a constantly changing array of visual culture. Brown limited the display and sale of his photographs to the homosocial setting of a saloon and only to other men, which was typical of the manner in which photographs from life circulated in the nineteenth century. But unlike in previous decades, now even respectable newspapers covered this type of story, thus making it available to any reader, male or female and young or old.

The simple economic reality was that the exploits of Anthony Comstock sold newspapers. He was Americas go-to man for obscenity, and a lightning rod for controversy that made good copy. If Comstock wasnt physically in your hometown during his career between 1873 and 1915, he was there in your hometown newspaper, fighting the purveyors of vice on the streets and in court, weighing in as a critic of art, theater, and literature, suffering editorial and physical attacks from his many enemies, being defended by ministers and moralists, and lampooned as a Puritanical knucklehead. Comstock dramatically changed American law and culture in ways that still resonate with us today. More than any other American in history, Comstock made vice, and vice suppression, into industries of monumental proportions, mutually bound in an ongoing cycle of production and suppression.

LUST ON TRIAL

LUST ON TRIAL