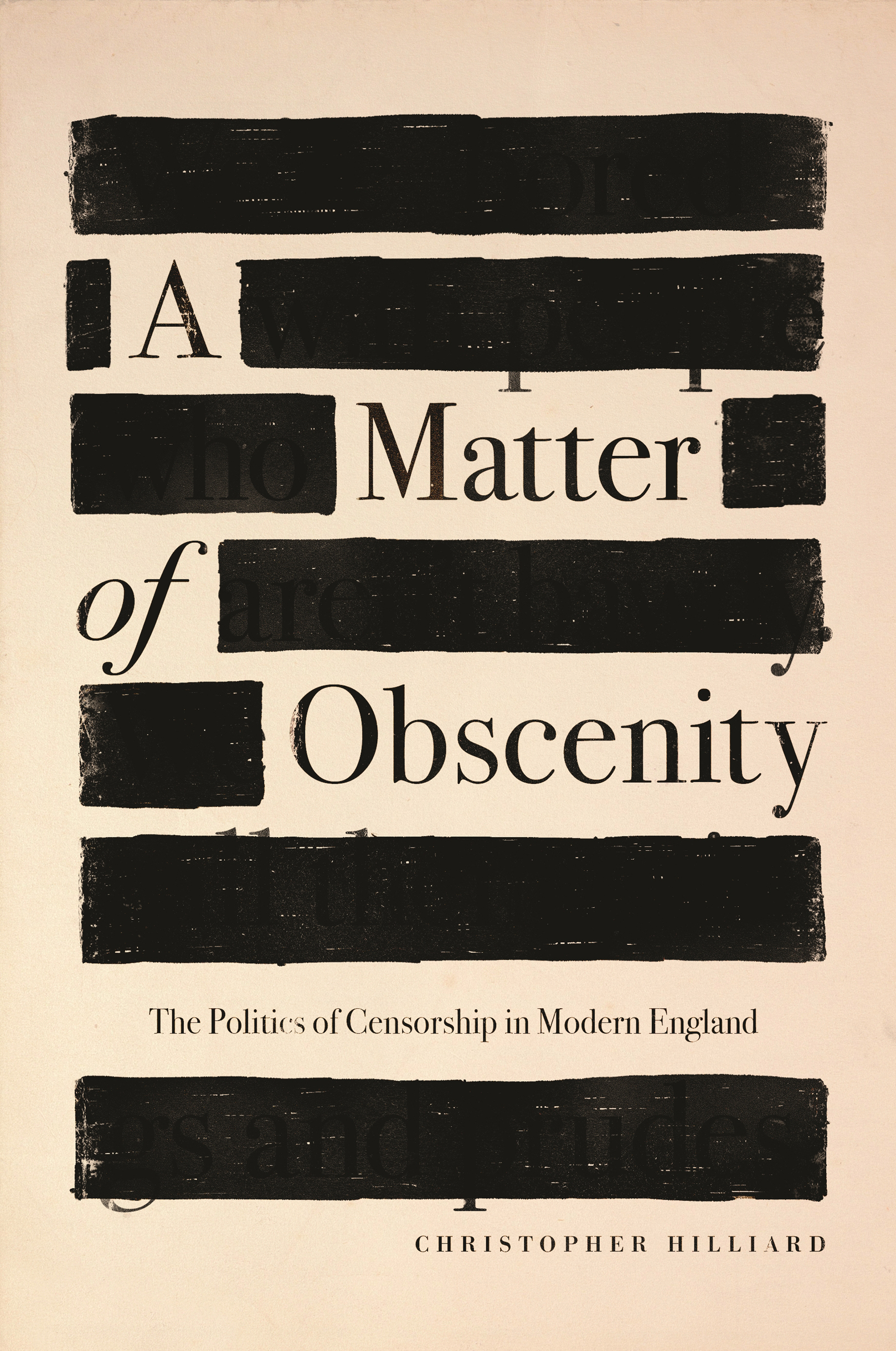

A MATTER OF OBSCENITY

A Matter of Obscenity

THE POLITICS OF CENSORSHIP IN MODERN ENGLAND

Christopher Hilliard

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-19798-2

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-22611-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021934950

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Ben Tate and Josh Drake

Production Editorial: Kathleen Cioffi

Jacket Design: Lauren Smith

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Amy Stewart

CONTENTS

A MATTER OF OBSCENITY

Introduction

MERVYN GRIFFITH-JONESS QUESTION in the Lady Chatterleys Lover trial is the most famous self-inflicted wound in English legal history. Prosecuting Penguin Books for publishing D. H. Lawrences novel three decades after the authors death, Griffith-Jones asked the jury how they would feel having the novel lying around at home: Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read? Griffith-Jones was used to cutting an intimidating figure in court. He had prosecuted Nazis at Nuremburg. But when he asked this question jurors laughed.

Griffith-Jones certainly was out of touch, but his argument would have been familiar to anyone who followed obscenity trials. Griffith-Jones repeatedly drew the courts attention to the low price of the paperback edition of Lady Chatterleys Lover. He made it clear that a paperback that working-class people could afford was an altogether different proposition from an expensive hardcover for scholars or collectors.

English obscenity law bore the imprint of Victorian debates about literacy and citizenship. The leading case on obscenity dated from 1868, months after the Second Reform Act extended the franchise to working-class men who met certain conditions. When Victorian intellectuals considered the implications of mass literacy their thoughts often strayed to the issue of suffrage. The question of how wisely working men used their literacy intertwined with the question of how responsible they would be as voters. One observer called literacy the literary franchise, playing with the idea that the ability to read and write was itself part of being a full citizen. Successive attempts to widen the electoral franchise wrestled with the question of what level of rent or income tax liability could serve as a proxy for the self-mastery required for the vote. Judges and prosecutors dealing with offensive books made analogous calculations. Obscenity law took income or wealth as an indicator of the responsibility a reader would need in order to avoid being corrupted by sexually frank books. Titles that might be tolerated in expensive limited editions risked confiscation if they were published in mass-market formats easily available to readers supposed to have weaker defenses than middle-class men. Officials, all of them men, worried about female readers too, but while price could divide readers on class lines, there was no equivalent device for keeping a book out of the hands of women while leaving it available to men. Keeping bad books away from women could only be the responsibility of the steady male head of a household. That patriarchal duty carried over from private life to jury service. Jurors wives and teenage daughters were often invoked in obscenity proceedings as people the law was supposed to protect. While the democratizing currents of the 1920s and 1930s made it dangerous for politicians to utter bald class judgments, and while slurs on womens mental and moral capacity later became risky too, the law remained a safe space for these attitudes for much longer. Griffith-Jones was not simply a throwback; his question was a glaring example of the way the timeframes of cultural change are not always in sync.

The prosecutors misjudgment created an opportunity to challenge these assumptions and the defense seized it. The whole attitude is one which Penguin Books was formed to fight against, the defense counsel, Gerald Gardiner, declared, continuing, This attitude that it is all right to publish a special edition at five or ten guineas, so that people who are less well off cannot read what other people do. Is not everybody, whether they are in effect earning 10 a week or 20 a week, equally interested in the society in which we live?

The Lady Chatterleys Lover trials synthesis of democratization and deference unwound within a decade. By the end of the sixties, the law was under attack from a new cohort of morals campaigners. And the anticensorship forces were now less likely to accept the distinction between art that deserved protection and trash that didnt. There was a shift from anticensorship arguments based on the special status of literature, or the need to test opinions in a marketplace of ideas, to seeing the freedom to read and write as an end rather than a means. This change was part of a more general move away from deference and conformitythe elaboration, as the historians Deborah Cohen and Jon Lawrence have shown, of traditional norms of privacy into an expansive ethos of personal autonomy and choice.

People who wrote to the Williams Committee explaining how they felt about censorship extrapolated from conventions of neighborly conductif you kept yourself to yourself, other people would let you beto arrive at a homespun version of the liberal principle that consenting adults could do as they wished in private, as long as immorality was not on public display. Others cited John Stuart Mills precept that people should be free provided their exercise of their freedom did not harm others. Many of those campaigning for personal freedoms in the sixties and seventies saw themselves as engaged in a struggle against the vestiges of Victorian morality, but this was also a struggle that pitted Victorian liberalism against supposedly Victorian morals. The gay-rights campaigners and porn magnates who quoted Mill to the Williams Committee were not necessarily Victorian liberals at heart: rather, the takeaway version of On Liberty was supple enough to articulate rights claims in a time of rapidly changing personal and cultural expectations.

Censorship has been an arena where ordinary people and officials alike wrestled with social changefrom the growth of literacy and democracy to second-wave feminism and gay rights, multiculturalism, and the impact of the internet. For a long time English obscenity law reflected uncertainties about what could be saidand, crucially, how and to whomin a changing society. This is as true of the 1860s as the 1960s. The law evolvedand didnt evolveas modern literature and popular culture took shape. The subjects of cases and controversies included penny dreadfuls, unexpurgated classics, sex-problem novels, risqu postcards sold in seaside resorts, modernist fiction, comic books, gangster novels, handwritten erotica, pornographic playing cards, avant-garde plays, television documentaries, pornographic magazines, the underground press, 8 mm films, horror movies, sex education, videocassettes, and online pornography. Many of these cultural forms were imports, the products of an increasingly international culture industry. Obscenity law was, among other things, a membrane through which foreign influences were filtered.