ALSO BY JULIA FLYNN SILER

Lost Kingdom: Hawaiis Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and Americas First Imperial Adventure

The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A . KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Julia Flynn Siler

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Siler, Julia Flynn, author.

Title: The white devils daughters : the women who fought slavery in San Franciscos Chinatown / Julia Flynn Siler.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | This is a Borzoi Book. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018039985 (print) | LCCN 2018054367 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101875278 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101875261 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Human traffickingCaliforniaSan Francisco. | Occidental Mission HomeHistory. | Social work with prostitutesCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory. | ChineseCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory. | Women abolitionistsUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesEmigration and immigrationHistory.

Classification: LCC HQ 316. S 4 (ebook) | LCC HQ 316. S 4 S 55 2019 (print) | DDC 306.3/620979461dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018039985

Ebook ISBN9781101875278

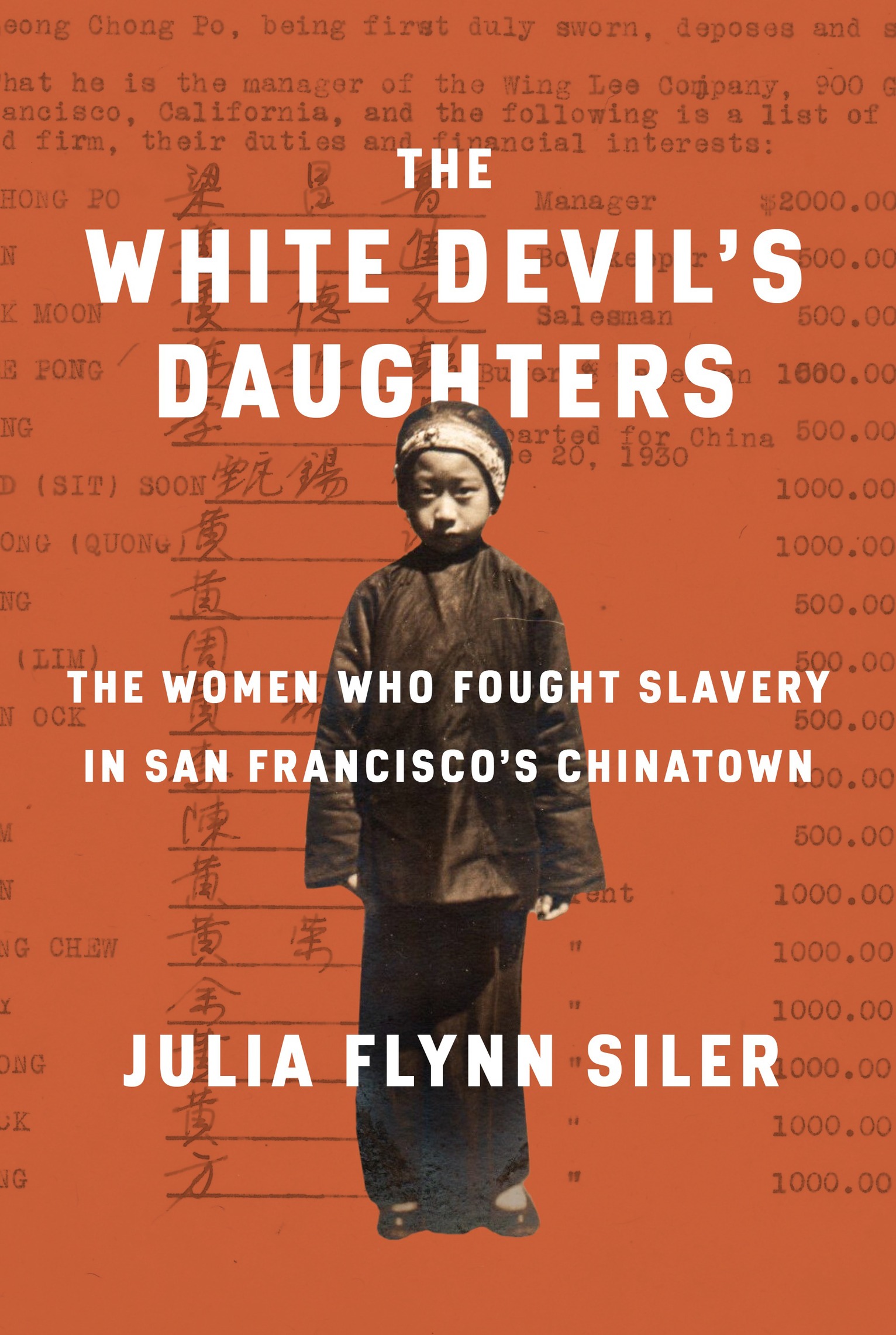

Cover images: (girl) Courtesy of Cameron House; (background) Partnership list of Wing Lee Company, San Francisco, CA. NARA.

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

v5.4

ep

Slavery can only be abolished by raising the character of the people who compose the nation; and that can be done only by showing them a higher one.

M ARIA W ESTON C HAPMAN , abolitionist, feminist

Contents

Preface

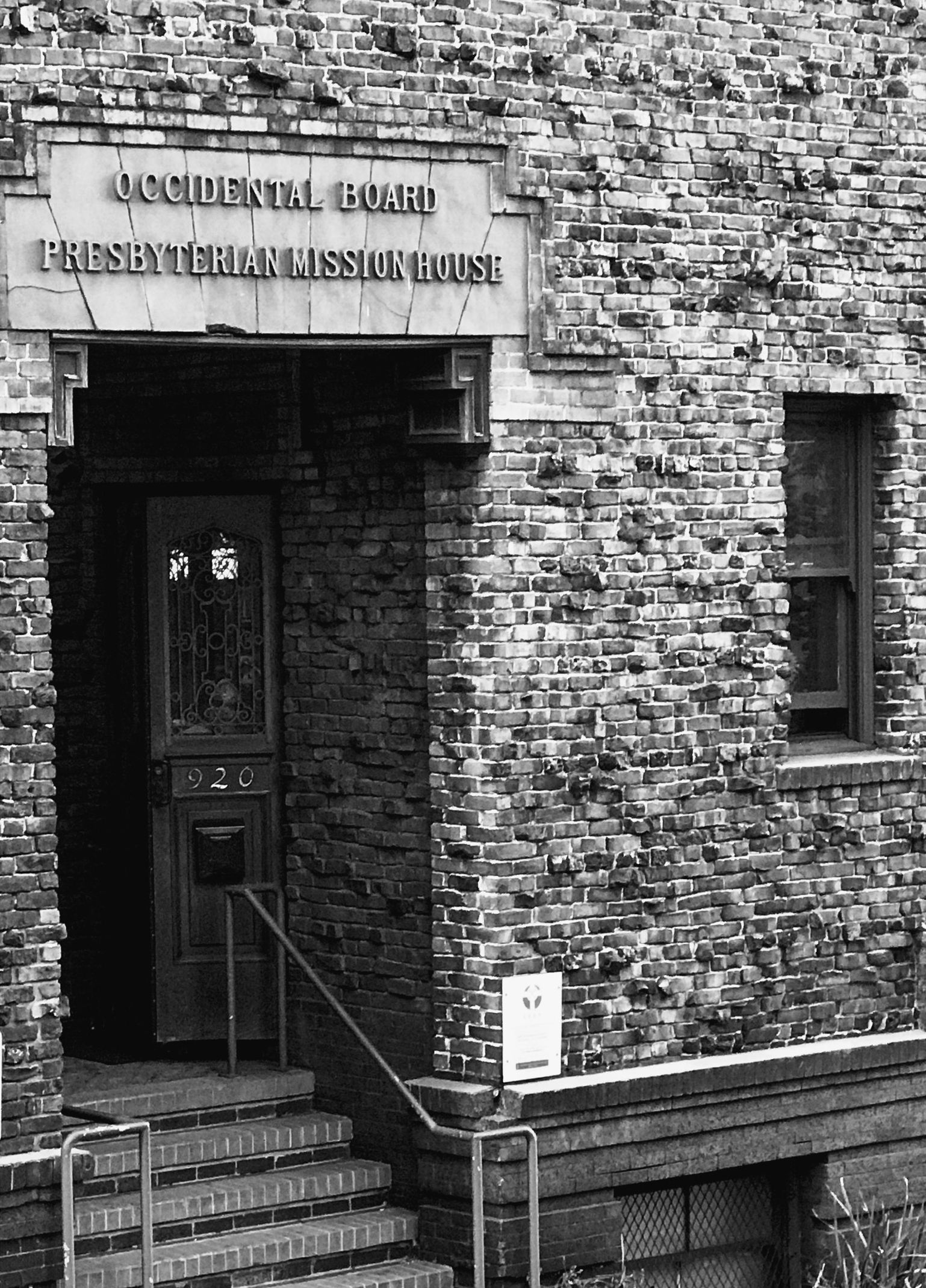

A ghost story first led me to the edge of Chinatown. One crisp morning, I dodged the crowds in Union Square and walked past a pair of stone lions up a hill. I had an address920 Sacramento Streetand a description. I was looking for a five-story structure built with misshapen red brickssome salvaged from the earthquake and firestorms that razed much of the city in 1906.

Passing a church and a YMCA, I came to an old building with metal grates on its lower windows. Above the main entryway, I peered up at century-old raised lettering that read,

O CCIDENTAL B OARD

P RESBYTERIAN M ISSION H OUSE

On a Plexiglas sign mounted onto the bricks at eye level, I read,

C AMERON H OUSE

E ST. 1874

I climbed the steps and pressed an intercom button. A lock clicked. I pushed one of the tall doors open and walked into a dark, wood-paneled foyer.

I first visited Cameron House in 2013; by then, it was mostly famous for being haunted. A staffer would later tell me hed once sensed a ghost in its musty basement. There, he said, terrified former slavesnearly all of them Chinese girls whod been sold or kidnappedhad hidden in one of its dark corners from their former owners. The girls and young women had lived there under the care of two remarkable immigrant womenDonaldina Cameron, the youngest daughter of a Scottish sheep farmer, and Tien Fuh Wu, a former household slave sold by her father to pay his gambling debts. Cameron served as legal guardian to most of the girls and teens living in the home. They called her Lo Mo, or Mother. She, in turn, often referred to them as her daughters. But Camerons enemies used a racist epithet to describe her: the White Devil of Chinatown.

For decades, Cameron and Wu engaged in what they called rescue workfreeing women and girls from sex slavery and other forms of bondage. An unlikely pair, they defied the conventions of their time and even, occasionally, broke laws to help other women gain their freedom. The home they ran at 920 Sacramento Street was one of the pioneering rescue missions in the United States, established more than a decade before the worlds first settlement house, Toynbee Hall in Londons East End, and fifteen years before Jane Addams co-founded Hull House to offer aid to Chicagos immigrants.

Starting with a trickle of women in 1874, and continuing over the decades, thousands of mostly Chinese girls and women entered the home. Many came from San Franciscos Chinatown, the ghetto of roughly eight square blocks that was North Americas largest and oldest Chinese settlement. In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, many women in Chinatown ended up working as prostitutes, some because they were tricked or sold outright by their families. They were forbidden to come and go as they pleased, and if they refused the wishes of their owners, they faced brutal punishments, even death.

From often-dusty records, I learned that the efforts of the homes founders, Victorian-era churchwomen, with their bustles, corsets, and elaborate piles of hair, were driven by compassion toward these enslaved women. They provided food, shelter, and the teachings of the Christian faith to members of an embattled immigrant community who faced discrimination and violence in San Francisco and across the West. Displaying grit and ingenuity, the homes founders overcame considerable resistance to build their rescue home at the edge of Chinatown, which was then considered by many to be the most dangerous section of the city.

The main entrance to 920 Sacramento Street.

Those who fled there were taking a leap of faith. The desperate conditions that led thousands of women to take shelter at the home are among the most searing stories from the saga of Chinese immigration to America. A decade after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished the slavery of African Americans, this other slaverythe trafficking of young Asian womenwas flourishing in San Francisco and throughout the West. And because Chinatown was in the original heart of the city, this brazen trade in human flesh was taking place just a few blocks away from both San Franciscos financial district and its most exclusive neighborhood, Nob Hill.

Today, the barest outlines of these brave womens stories fill a large bound ledger that still sits in a small, locked archive room on its top floor. In careful handwritten script, the book lists more than eight hundred names of women and girls who took refuge at the Mission Home from its founding in 1874 until January 1909. Nearly a thousand more womens names from the decades after that are recorded in its case files. Further clues about their lives are buried in immigration records at the National Archives, and a few of its residents, such as Wu, left moving firsthand accounts.

The house at 920 Sacramento Street has a haunted history. Few people are aware of it, because human trafficking and sex slavery, until recently, have been largely unexamined corners of the American experience. Yet the story of how the home offered a gateway to so many daughters of joy, as prostitutes were sometimes called, is contained within the lined pages of its ledger book and offers tangible proof of the astonishing journeys these women made. They escaped their bondage, they found refuge in an ungainly brick house on Sacramento Street, and they embarked on a fight for freedom that continues today.