Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2021 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

Copyright 2021 James H. Bruns

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-011-4

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-012-1

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States by Sheridan

Typeset in India by Lapiz Digital Services.

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

Contents

For Chris, Don, Dan, Mandy, Joe, and James

Preface

This book focuses on the reasons, reactions, and results of Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Earlys raid on Washington, DC, in 1864. These three aspects have been overlooked in many of the earlier narratives of the raid, works that have tended to concentrate on the battles and leaders. And, unlike all the other narratives of this kind, this work highlights the forgotten naval role in the 1864 scheme to free Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout, Maryland, and its implications.

Welcome to Civil War-era Washington. The District of Columbia had been the seat of government since 1790, and for much of its early existence it was considered a relatively sleepy Southern town that in 1860 had a population of roughly 75,000. The city was unbearably hot and humid in the worst of summer. Manure-laden dust storms and its swampy location made it prone to typical Southern seasonal diseases. In the heights of winter, it was icy and windswept, with streets that could resemble rivers of thick, frosty, gumbo-like muck. The citys heavy-eyed character changed dramatically with the onset of the Civil War. Almost overnight the district was transformed from a quiet community into a massively important centralized hub of bureaucratic and public activity that was needed to sustain the war effort. The population at times swelled to as many as 200,000 inhabitants. Overcrowding and a lack of adequate housing and sanitation were major problems. Cleanliness suffered as the city witnessed an intensity of military, civil, and bawdy activities at a previously unknown scale.

As the center of Union management of the war, Washingtons safety was seriously threatened several times, including in 1862, when the Confederacys Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland, culminating with the battle of Antietam, and again in 1863 with that same Rebel armys invasion of the North, resulting in the battle of Gettysburg. In each of these instances, the Federal city wasnt the target. That changed in 1864. And the third time wasnt a charm. It was considered a serious threat. Or at least thats what weve been led to believe for 155-plus years. But was it?

While many previous books on the subject of Jubal Earlys raid on fortress Washington have focused largely on the military aspects of that incursion, this book concentrates more on the feelings, fears, and facts of the regions civilian population, its causal connections, and its results. Because misinformation was rampant, this book examines the civilians thoughts, anxieties, and frustrations over the lack of accurate news regarding their safety and their keenand perhaps morbidcuriosity with what was going on at the nearby killing fields about them.

President Abraham Lincoln was one of those who was drawn to the battlefront like a moth to a bright flame that steamy summer. On several occasions he visited the frontlines and was even reportedly deliberately shot at by Confederate sharpshooters. If true, that made him only the second chief executive known to have faced enemy gunfire while in office (the other was James Madison at the 1814 battle of Bladensburg, which took place only a few miles away to the east from where Lincoln reportedly faced enemy fire).

But I believe that the stories about Lincoln thoughtlessly facing gunfire at Fort Stevens and nearly being shot have been greatly overblown over time. The nature of the Confederate raid on Washington, I believe, has also been greatly misinterpreted. While there were various important goals each time the Confederates invaded the North, Jubal Earlys maneuvers were in fact only the latest in a series of annual Southern food raids. The Confederacy had made such incursions in September 1862, culminating with the battle of Antietam; in July 1863, ending with the battle of Gettysburg; and now, again, in July 1864, climaxing with the standoff in front of Fort Stevens. Each time, foraging for food was a major aspect of these operations.

As early as 1862, General Robert E. Lee was intrigued with the idea of attacking Washington, but he accepted the limitations of his situation. As he told President Jefferson Davis, I had no intention of attacking (the enemy) in his fortifications and am not prepared to (besiege) them. If I possessed the necessary munitions, I should be unable to supply provisions for the troops. That opinion wouldnt change in 1864. Instead, in 1862 and 1863 Lee would merely threaten Washington, while gathering food and supplies for his needy army. In addition to provisions, Lees army in Maryland and Pennsylvania in 1863 also rounded up large numbers of runaway slaves and herded them back South. July was the perfect month for such maneuvers. It cleared the Shenandoah Valley of bluecoats during the Southern harvest season, and it coincided with low water levels on the Potomac and other river gateways to the North.

The Northern territory that was plundered was always the same, including what became West Virginia in 1863, western Maryland, and southern Pennsylvania, all largely pro-Union regions, but in 1864 Jubal Earlys force would pillage deeper into the heartland of secessionist Maryland. The pastures he plundered were largely productive pro-Southerners farms.

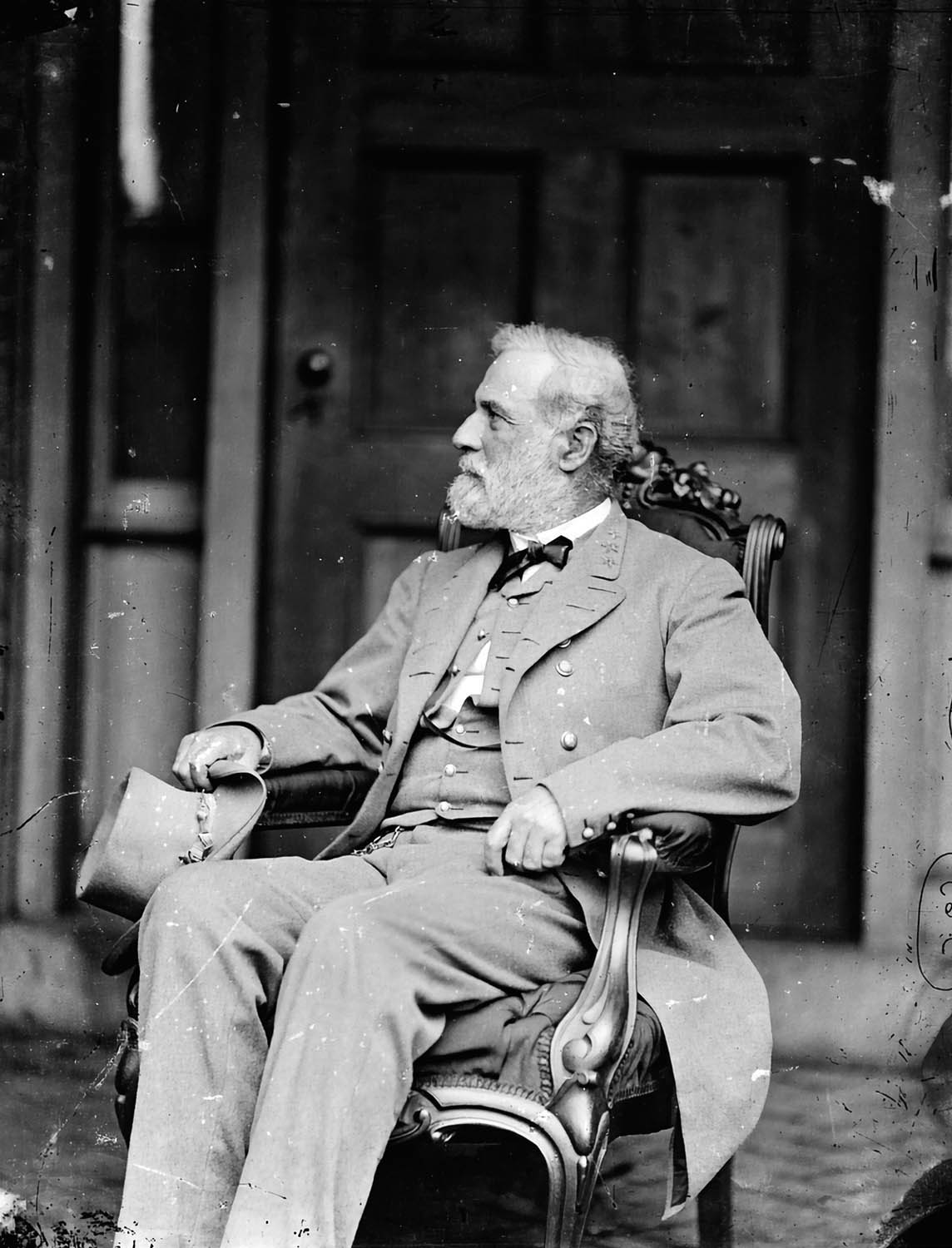

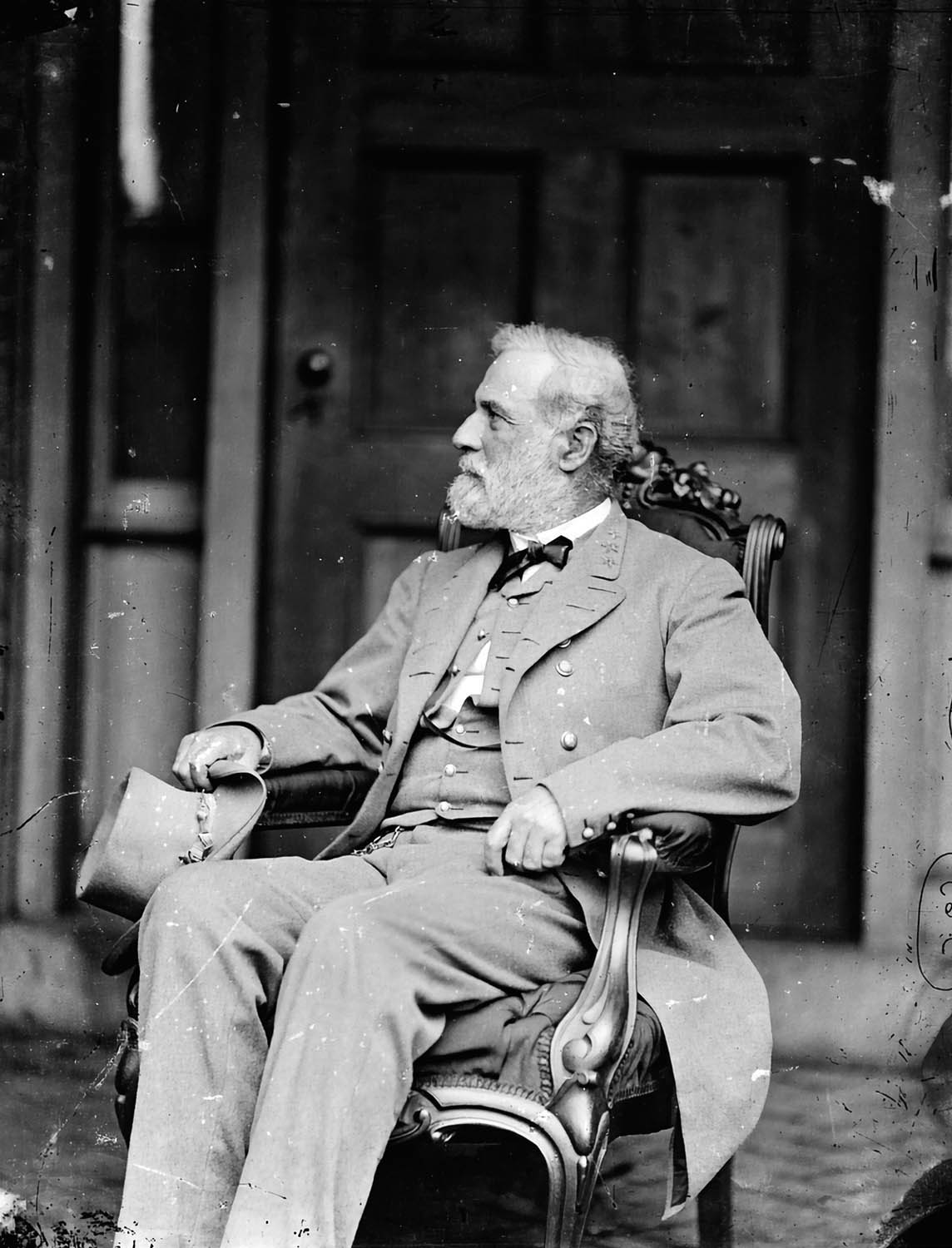

Robert E. Lee took Richard Old Baldy Ewells command of the Second Corps away from him in the spring of 1864 and gave it to Jubal Early. Ewell, a native of the District of Columbia, was given command of the defense of Richmond until its fall in April 1865. (Library of Congress)

In this regard, the Rebel army in the North was like a biblical plague of locusts. In 1862 the Rebels made off with large quantities of food, fodder, and supplies. One Maryland resident complained that after the Confederates arrived, The farmers didnt have no chickens to crow and, according to Union medical officer William Child, the assistant regimental surgeon with the 5th New Hampshire Infantry, the farms around Antietam Creek were completely picked clean. The man with whom I stop has not an apple, peach, sweet or Irish potato left, he noted, adding, he would have had great quantity of each had no army passed this way. In advance of the Rebels marching into Maryland in 1862, many farmers fled north with their horses and livestock, but their crops were left up for grabs. Harvests already put up in barns were hastily taken, as were any remaining animals. The following summer, the Rebels returned, again hoping to abscond with more food and animals.

Next page