First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John C. Carr 2015

ISBN 978 1 78383 116 6

eISBN 9781473856332

The right of John C. Carr to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Prologue

N inety-eight men and four women occupied the Byzantine throne from the inauguration of the empire on Monday morning, 11 May 330, to its elimination in a welter of blood and fire in the early hours of Tuesday, 29 May 1453. These include the seven Latins who reigned during the fifty-seven-year occupation of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusaders and their descendants in the thirteenth century, plus those Byzantines who did not submit to the Crusader occupation and remained legitimate in exile. The story starts conventionally from Constantine I; but to him the term Byzantine emperor would have been a curious one, as he was, and considered himself, a lineal Roman emperor in the Augustan tradition. Of the ninety-eight male emperors (a few of whom were momentary or mere infants), forty-eight roughly half can be considered fighting emperors in that they personally took the field against Byzantiums enemies at some point during their reign.

The human heart, wrote Marchal de Saxe, an eighteenth century French strategic theorist, is the starting point of all matters pertaining to war. Such a view has not been popular among military historians since about the middle of the twentieth century, when social and economic theory began to cast their dreary mists over the discipline. Now the great determinisms economic, geographical and neo-Freudian have given way to a kind of technological super-determinism. Modern warfare, with its unmanned drones and algorithmic combat simulation and analysis models, would seem to depend less on de Saxes human heart than on dropping and dragging icons on a computer screen.

If there is any broader narrative to note, it is the very dramatic one of a Christian empire which spent a thousand years preserving civilization in an eternally troublesome corner of the world, and which ultimately went down fighting with supreme heroism in defence of Christendom and the preserved treasures of Greek and Roman culture on which the intellectual and spiritual structure of the West has been built. These treasures are always under threat, not least from within the western world itself. The fighting emperors of Byzantium personally battled to safeguard their world, their people and Christianity. Some won, some lost.

Of course, the role of a monarch now is vastly different from what it used to be. It is hard for us today to envision a fighting monarch. For the past few centuries being a king or queen has meant leading a comfortable, privileged and highly protected life as head of state, a ceremonial figurehead. The full resources of state security are employed to ensure that such people and their families do not run the slightest risk of personal harm and are protected on every side for their entire lives. Such coddling would have been incomprehensible in past ages when a monarchs prime duty was to protect state and people by riding at the head of the army and putting himself (and sometimes herself) actively in harms way. If a king or emperor was not up to the job, either by age or character, either his princes filled in for him or he was none-too-delicately removed and replaced by someone tougher.

In the seventeenth century Edward Gibbon noted acidly that the generality of princes, if they were stripped of their purple and cast naked into the world, would immediately sink to the lowest rank of society, without a hope of emerging from their obscurity. But the term generality does allow for exceptions. If there is any royal figure in our own age, for example, who has shown signs of having the stuff of a fighting king, it is Britains Prince Harry. Having served as a combat helicopter pilot in Afghanistan, he has not flinched from risking his life for his country. Third in line to Britains throne until July 2013 (when the birth of his elder brother Prince Williams heir George Alexander Louis put him back several slots), Harry will not become king unless extraordinary circumstances intervene. But it may be sobering to note that in earlier times such extraordinary circumstances were common murder, enemy action, court intrigue, disease or that distressingly frequent phenomenon in royal annals, the hunting accident.

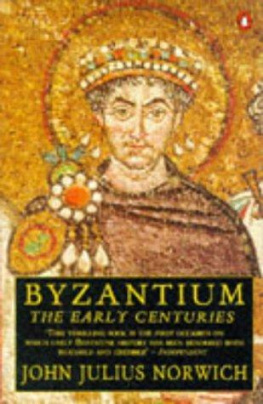

Until about a hundred years ago it was normal, in the Anglo-Saxon world at least, to dismiss the 1,123-year saga of the Byzantine Empire in the words of W.E.H. Lecky, as: a monotonous story of the intrigues of priests, eunuchs and women, of poisonings, of conspiracies of perpetual fratricides. There were plenty of those, to be sure, but more positive attitudes saw the light in the twentieth century thanks to outstanding scholars such as Will Durant in America and Sir Steven Runciman and later John Julius Norwich in Britain.

The material on Byzantium is, of course, vast, and anyone wanting a rounded picture of the empire cannot do better than read Lord Norwichs riveting three-volume Byzantium , the despair of anyone else trying to write about the subject. I realized early in my own project that to compress eleven tumultuous centuries of imperial history into a single moderate-sized volume, even limited to the military aspects, would be a considerable task. So I have concentrated the chapters around the main fighting emperors, leaving regrettably little room for the others. Much of interest has had to be left out. I describe every Byzantine emperor who ever went into combat primarily in human terms and only secondarily as part of a process or supposed wider political phenomenon. Men are everything, said George Canning, a nineteenth century British prime minister, measures comparatively nothing. I make no pretence at academic rigour or precision; what follows are stories of flesh-and-blood people and the military and political challenges they were called upon to meet.

I can only hope that what remains is not too sketchy a pageant, and so let the curtain open on the royal protagonists of a grandiloquent, jewel-encrusted period of military history that has not yet had the full recognition it deserves in Western historiography, but richly rewards those who delve into it.

John C. Carr

Athens, June 2014

List of Plates

Chapter One

From Rome to Byzantium: Constantine the Great and his Successors

L ate in October 312 Flavius Valerius Constantinus, commanding a Roman army composed mainly of Gauls and Britons, scanned the wooded hills north of Rome. After weeks of hard marching across Europe, over the snowy Alps and down through the plains of Italy, fighting most of the way, he was finally within sight of his goal. One more battle and Rome, the seat of the greatest empire the world had ever seen, soon to celebrate a thousand years since its founding, would be his.