Velodrome Racing and the Rise of the Motorcycle

Also by R.K. Keating

Wheel Man: Robert M. Keating, Pioneer of Bicycles, Motorcycles and Automobiles (McFarland, 2014)

Velodrome Racing and the Rise of the Motorcycle

R . K. Keating

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Names: Keating, R. K., 1951 author.

Title: Velodrome racing and the rise of the motorcycle / R.K. Keating.

Description: Jefferson, North Carolina : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021000463 | ISBN 9781476681436 (paperback : acid free paper) ISBN 9781476641607 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Motorcycle racingHistory. | VelodromesHistory.

Classification: LCC GV1060 .K38 2021 | DDC 796.7/5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000463

British Library cataloguing data are available

ISBN (print) 978-1-4766-8143-6

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4766-4160-7

2021 R.K. Keating. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

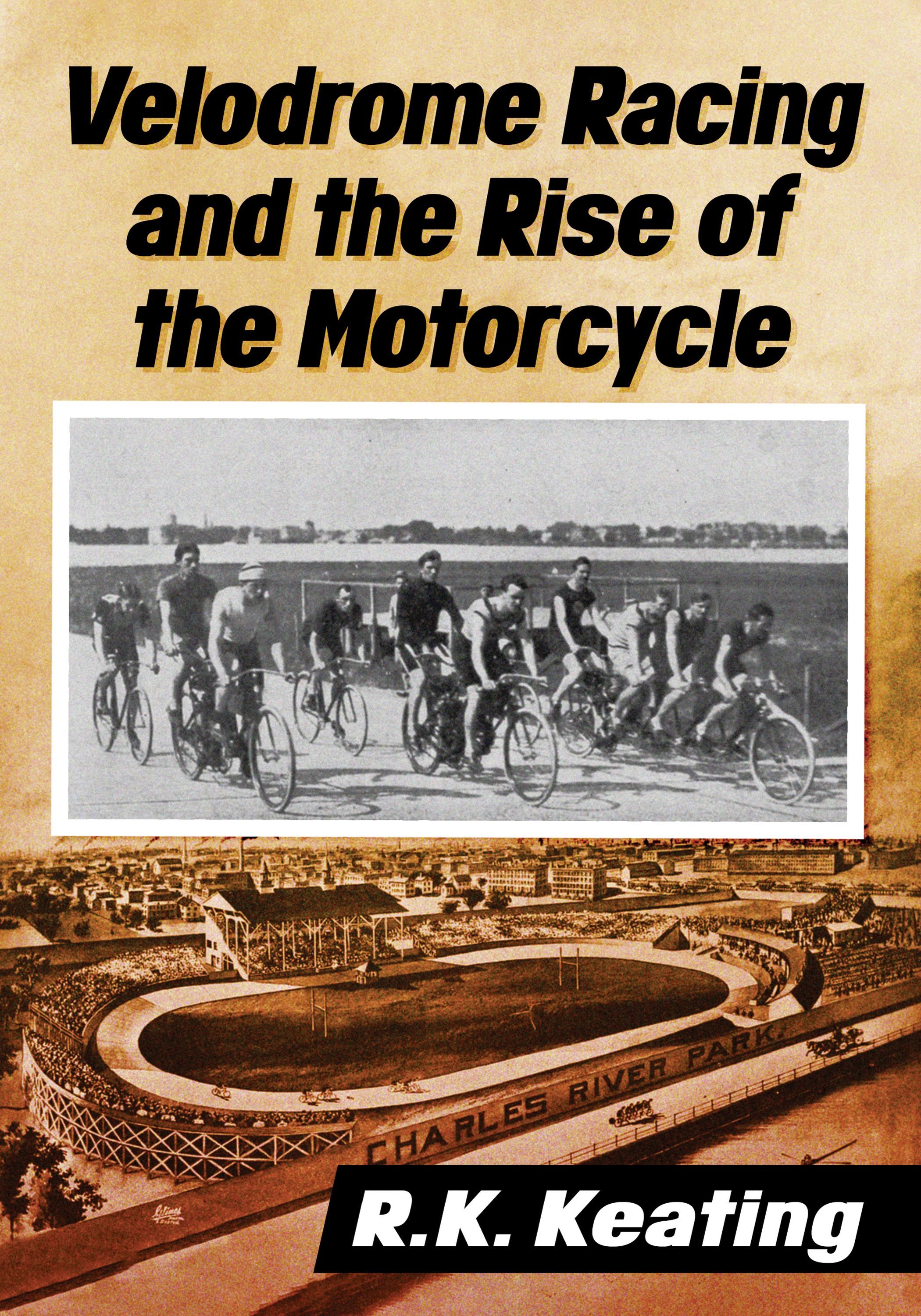

Front cover images: background The racetrack at Charles River Park, Boston, Massachusetts, 1897 Referee , 2-25-1897; Inset The start of the July 15, 1899 race at Manhattan Beach racetrack. From left to right : Earl Stevens behind Fourniers original French motor tandem, Burns Pierce behind an Orient motor tandem and Elkes (blocked by the previous machines) behind the Orient motor quad with Fournier working the motor. Automobile , January 1900

Printed in the United States of America

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Matt and Ben, the keepers of the flame

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

The inspiration and motivation that led to this book originated with the writing of my first book, Wheel Man , which chronicled the life and times of Robert M. Keating and his Keating Wheel Company and later, the Keating Wheel and Automobile Company. In the 1890s he produced the Keating bicycle and by 1900 several automobiles and one of the first motorcycles in the United States to go into commercial production. This book takes some of the rich background that surrounded and engulfed Keatings introduction to and adaptation of motor power and gives it a story of its own.

There were a number of people, organizations and institutions that provided important access to source material and/or provided relevant information in support of Wheel Man and much of that original background material was layered onto this book. Among those whose original information was fully or partially incorporated into this book include Christopher Matson, Green Library, Stanford University, Stanford, California, and John Knapik, Westfield Historical Commission, Westfield, Massachusetts. A special shout-out is in order to Andrew Richie, author of numerous books including Quest for Speed , recently republished by McFarland, which outlines in great detail the history of early bicycle racing in Europe and America. That quest for speed was the catalyst that transformed pedal-power on the bicycle track into motor-power on the Velodrome and later the motordrome and speedway. Several early telephone conversations and emails with Andrew reassured me that there was a story to tell in that transformation and for that I thank him. The Archives and Library Staff of the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford Museum were also very helpful. Their holdings include a treasure-trove of information, in rare early photographs, that address not only the development of the automobile but also the early motorcycle in America. Also, Maryann Butterfield of the Christchurch City Library System in New Zealand was helpful in identifying various photographs and providing commentary. The staff of The Wheelmen were also very helpful and generous with their assistance with articles on the subject of early bicycle racing and pacing. Jim Merrick, Archivist at the Stanley Museum provided some important detail on the Stanley steam tandems used by racing competitors Eddie McDuffee and Major Taylor, and the later Locomobile No. 1valuable material for which I am grateful. Erik Meesters, a fellow author and motorcycle historian based in the Netherlands, uncovered valuable source information and original photographs from various European newspapers and journals. His enthusiasm and generous commitment of time was special.

A very big thank you must go out to Patricia Mardeusz, Reference Librarian at the Bailey/Howe Library at the University of Vermont for some very early research help that, unbeknownst to either of us at the time, helped structure the narrative of this book, giving it a vantage point from which to view the story from front to back. In response to my request, she sent along a short article from the August 26, 1899, edition of Leslies Weekly entitled Revolutionizing Bicycle Racing. Included in the article was a rare photograph of a motor quad (a bicycle built for four with a De Dion-Bouton petroleum motor), built by the Waltham Manufacturing Company. Sitting on the real seat was a character sometimes lovingly referred to as The Crazy Frenchman, whose real name was Henri Fournier. After a few weeks of digging it became clear to me that Fournier and his motor machines were both very special and provided an historical spark that took America from petal-power to motor-power in a years time. It was one of those rare, unexpected and inspiring episodes in the writers realm when a grand idea is suddenly brought into laser focus, begging to be transferred into text that, with any luck, might be unleashed unto the world in a clear and entertaining form. The first part happened; you will be the judge of the second part.

I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the assistance of my wife Maryann, who from time to time would ask how the writing was going and check in to see that I was not just typing gibberish. I needed the reassurance that the words were making sense and she needed to make sure I had not been transformed into Jack Torrance. I, of course, continue to receive inspiration and motivation from my siblings and their families to pursue writing on all things cycle. From my immediate family, their unwavering support, unconditional understanding and infinite patience, allow undertakings like this to be pursued. I am eternally grateful to all.

Preface

If necessity is the mother of invention, then the nineteenth century cyclists need for speed most certainly spawned the infernal machines that evolved into todays motorcycles. These early motor machines, whether powered by accumulators, boilers or petroleum, were simply the tools of the trade for the bicycle-racing speed kings who quickly adopted the science of pacing to assist them in smashing any and all time and distance records on the racetrack. Over time, what were once tools became the main event, filling the bleachers at the tracks, the trophy cases of the racing stars and the pockets of track owners and promoters. For a while, the use of pacing machines actually revitalized the sport of bicycle racing, which had at times seen serious droughts in interest, spectators growing tired of watching tedious processions of bicycles circling the track in single file until a last-minute sprint determined a winner. The use of pacing machines not only excited racing fans, but it also encouraged the construction of new spectator-friendly velodromes. These outdoor and indoor high-banked board tracks sprung up all across the country, forming a racing circuit that put bicycle racing in front of tens of thousands from Memorial Day through Christmas every year, making it Americas number one sporting event. But once these pacing machines became motorized, everything changed. Think telephone versus cell phone.