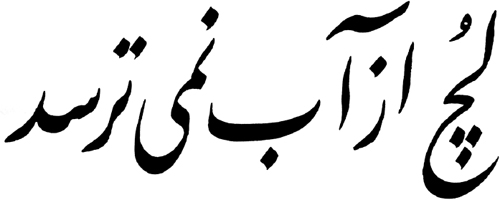

The naked dont fear the water.

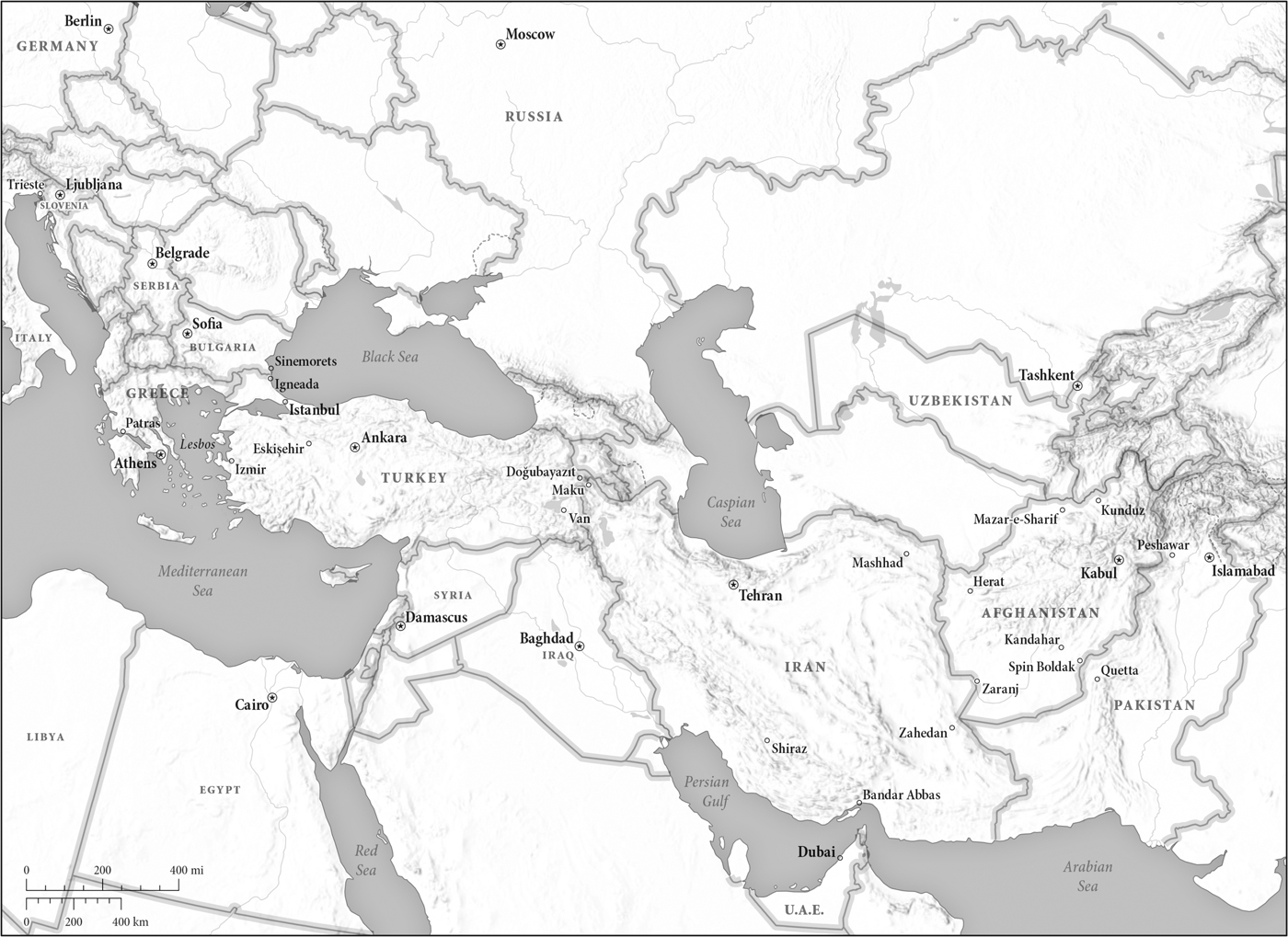

A t first light, I leaned against the window and looked down at the mountains. We were flying into the rising sun, and its rays threw the badlands into relief: corrugated brown cut by green valleys, and speckled with hamlets still reached by donkey. We were near the intersection of Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan, but which country I saw below I couldnt say. Frost had crystallized on my porthole, rosy with the dawn just like our contrails would be to the people below.

I settled back against the headrest. We were still a few hours out from Kabul, where my friend Omar was waiting for me. When I closed my eyes, I could see his face when he dropped me off that summer at the airport, suddenly pleading, his hand gripping mine: Come back, brother. Dont leave me. Everyone else is leaving.

The plane was quiet. The few passengers I could see were slumped forward or sprawled out asleep across the rows. These empty places would be filled on the return to Istanbul, I knew, with Afghans fleeing the war. My own seat might be taken by someone who planned to cross the water in the little rubber boats that departed from Turkey to Europe. Thousands of refugees were landing each day now on the Greek islands, and many more were on the way. It was late October 2015, and something miraculous was happening that fall, a violation of a fundamental law: under the weight of the people, the border had opened.

For years, the pressure outside Europe had been building as war spread through the Middle East and made millions homeless. The boat people were mostly Syrian, Afghan, and Iraqi. Many were women and children, and, short of shooting them, there was no way to stop them. From Greece, they headed north through the Balkans, filling city squares and border crossings, a spectacle on the news, a crisis. To keep the European Union from tearing itself apart, Germany suspended its rules and let the migrants through; other countries followed suit, and now the five frontiers between Athens and Berlin were down. Screens around the world showed the masses walking through open borders, proof of the impossible, a clarion announcing universal freedom of movementa dream for some, and a nightmare for others.

No one knew how long the miracle would last. Thousands of people were landing each day now in the little boats. A million would pass into Europe.

And Omar and I were going to cross with them.

W E HAD MADE OUR DECISION back in August, when Id returned home to Kabul after an assignment in Yemen. Id known Omar since Id started working in Afghanistan, and hed always dreamed of living in the West, but his aspiration had grown urgent as the civil war intensified and his city was torn apart by bombings. American soldiers were on their way out of the country; I was trying to move on, too, burned out after seven years reporting here, but I couldnt leave Omar behind. So when Id flown back earlier that summer, my friend had been on my mind. I had no plan yet, but an idea was taking shape. Omar and I needed to talk.

WELCOME TO HAMID KARZAI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT . At the immigration counter, I handed over my passport and placed my fingertips on the green glow of the scanner, then walked to the baggage carousel and got my suitcase, wheeled it to the X-ray machine. The cop at the monitor was looking for guns and bottles. Alcohol was illegal in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, except at the embassies and international agencies, but foreign visitors were allowed to bring in two precious bottles each. I hefted my suitcase onto the conveyor belt, along with the bag of scotch and gin from the duty-free in Istanbul, and walked to the other end, rehearsing my lines.

My ancestors came from Japan and Europe, but I look uncannily Afghan: almond eyes, black hair, wiry beard. So the border guards invariably assumed that I was a local with haram contraband, a lucrative catch, since the confiscated booze would likely end up on the black market. Over the years, my Persian got better, but that just made the conversations more awkward.

Brother, are you telling me youre not Afghan?

No, sir, Id say, scrambling around the belt with my passport before the cop could snatch the bottles. Look at my name, Im not even Muslimsorry.

Outside the terminal, I inhaled the dry summer air. I hadnt been sleeping much since Sanaa, but my tiredness left me as the scene came into focus: faraway snowcaps of the Hindu Kush, the slums on the hillside, the Humvee with its turret pointed at the gate. In the parking lot I spotted a gold Toyota Corolla and, listening to the radio with the window down and a cigarette lit, my friend Omar. He got out and walked forward: taller than me, broad-shouldered, with a fleshy grin and crows-feet. As we embraced, the heat made his stubble prick against my cheek; he smelled of cologne and smoke. Prying my suitcase from my hand, Omar hefted it into the trunk. We drove into the roundabout outside the airport, a gyre of taxis, armored SUVs, buses, the policemen shouting, the beggars tapping windows, the peddlers swinging racks of phone cards and dashboard ornaments. Omar nosed the Corolla forward, cursing softly, one hand on the wheel and the other clutching a Pine, from time to time leaving it between his lips to run his fingers through his dark mop of hair. It wasnt until we got out onto the airport highway, with its long stretch of cavernous wedding halls, that we could relax and catch up.

Its good that youre back, baradar, he said in Persian. He smiled but kept his eyes on the road.

Its good to see you too, brother, I said.

He knew my lease was expiring, and that Id come back to clear out the house. It seemed like half the city was escaping that summer of raftan, raftangoing, going. Afghans were losing hope in their countrys future. The middle class spent their savings on flights and visas to Turkey; young men filled buses departing for the southern desert near Iran. Omars own family was leaving. Four of his siblings were already in Europe, and his mother and sister were getting ready to escape with smugglers. But for a long time, Omars plan had been to emigrate to America through the Special Immigrant Visa, a program created by Congress to reward loyal Afghan and Iraqi employeesa happy ending for a few, to soothe Americas conscience. Omar should have qualified; hed served in combat as an interpreter for the Special Forces, and worked with USAID and demining contractors. But when he sent his application to me, I saw that he was in trouble. He needed all sorts of paperwork that hed never thought to collect over the years: letters of recommendation from his supervisors, copies of his employers contracts with the US government. How was he supposed to track down a Green Beret captain he knew only by first name? Or get documents from the demining company, which had gone out of business? Hello my dear and sweet brother, he emailed while I was abroad. I hope you are fine and doing well. Please wish for me best of luck and find the chance to get the US visa and move there. I am really tired of life here.

We sent in everything he had. It took two years for the answer to come back: We regret to advise you that your application for Chief of Mission (COM) approval to submit a petition for the SQSpecial Immigrant Visa (SIV) program has been denied for the following reason(s): Lack sufficient documents to make a determination....