Copyright Patrick Brode, 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

FIRST EDITION

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Brode, Patrick, 1950-, author

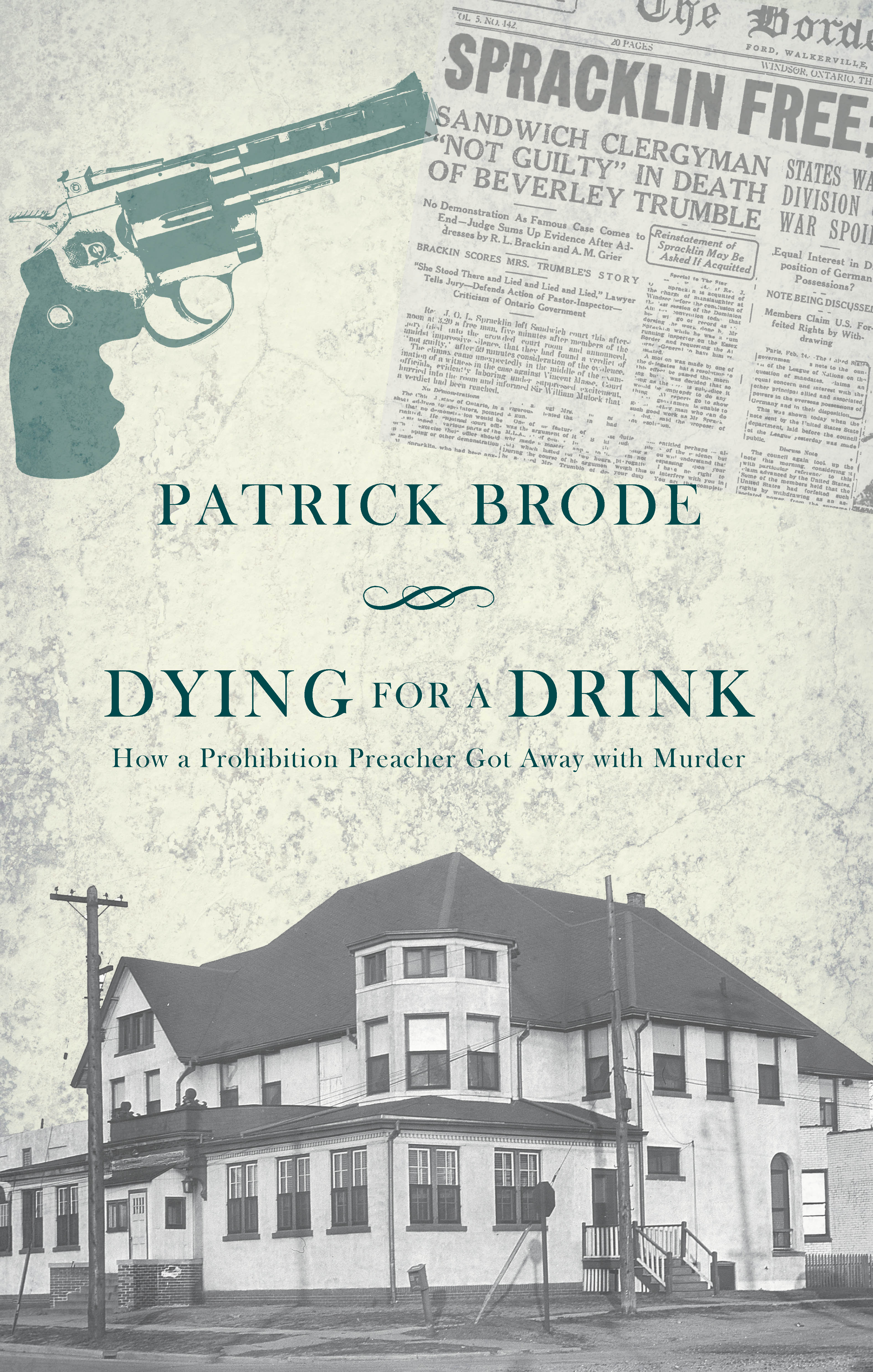

Dying for a drink : how a prohibition preacher got away with murder /

Patrick Brode.

ISBN 978-1-77196-268-1 (softcover).ISBN 978-1-77196-297-1

1. Trumble, Beverly--Death and burial. 2. Spracklin, Joseph Oswald Leslie, 1886-. 3. Prohibition--Ontario--Windsor. 4. Temperance--Ontario--Windsor. 5. Murder--Ontario--Windsor.

I. Title.

HV5091.C3B76 2018 364.13320971332 C2018-901746-5

Edited by Sharon Hanna

Copy-edited by James Grainger

Typeset and designed by Chris Andrechek

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country, and the financial support of the Government of Canada. Biblioasis also acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council (OAC), an agency of the Government of Ontario, which last year funded 1,709 individual artists and 1,078 organizations in 204 communities across Ontario, for a total of $52.1 million, and the contribution of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

Introduction

On November 6, 1920, two men confronted each other in an armed standoff in the town of Sandwich, Ontario. One of them would die.

Beverley Babe Trumble, one of the combatants, was a rough and tumble tavern keeper. He was known to sell liquor and beer to Americans in his popular roadhouse, the Chappell House. The man challenging Trumble that evening was an enforcer acting on behalf of the provincial government. But not only was he a licensed officer of the law, he was an ordained minister of the Methodist Church of Canada. The Reverend J.O.L. Spracklin was already something of a legendary figure across Ontario for his no-holds barred approach to imposing the temperance laws. Disdaining any need for search warrants or other legal niceties, Spracklin and his special agents had been bursting into liquor dens and administering their own personal brand of justice to those who defied the morality laws. On the evening of November 6, Spracklin and his men had broken into the Chappell House in search of contraband liquor. Trumble, an individual who stood by his rights, was determined to resist them.

This confrontation, which must have lasted only a few seconds, was in many ways the high-water mark of the temperance movement that had been such a powerful political force in Ontario for decades. It was a collision between evangelical Ontario, which considered the consumption of alcohol to be an unforgiveable evil, and a modern society that welcomed a more liberal lifestyle. For moral purists such as the Reverend Spracklin, drinking was a vile habit that robbed men of their free will and diverted them from their responsibilities to their families. On the receiving end of Spracklins fire was a roadhouse operator who represented what the province was becoming: a consumer-oriented, leisure-seeking culture that defied Victorian mores. The Jazz Age was about to explode, and it would resist attempts to rein in its exuberance. Some entrepreneurs were determined to meet the needs of this emerging materialistic society and profit by it. Babe Trumble was one of these visionaries, and it was his misfortune to cross paths with one of the most zealous defenders of the old ways.

Significantly, this confrontation took place on the Detroit River border, in a transnational area that was neither entirely Canadian nor American. With a diverse population that came from more metropolitan parts of Europe, and with a significant non-Protestant element, the Windsor border area (usually referred to as the Border Cities) did not conform to the expectations of the rest of the province. Moreover, the inhabitants looked to the adjacent American metropolis of Detroit for the lead on cultural and social affairs rather than to the distant provincial capital of Toronto. Early on, the Toronto press grasped that the Detroit River border was different, and they reported on developments on this frontier almost as if they were reporting on events in a foreign country. Their readers thrilled to accounts of heavily armed gangs fighting it out for liquor caches secreted in Essex County hideaways. Toronto reporters described how rumrunners who had lived their lives along the shoals and backwaters of the Detroit River braved the enforcers of American Prohibition to run shipments across the international border. Those who lived at a safe distance from these events were either entertained or appalled by the lawlessness along the western border.

In the eyes of some, particularly those in the evangelical movement who had struggled through their lives to foster a temperate, alcohol-free Ontario, something had to be done to bring this unruly region to heel. After decades of struggle and numerous referenda, the movement had finally prevailed in the Ontario Temperance Act of 1916. The saloons were closed, and the sale of liquor and beer made a thing of the past. The movement to abolish the bar had the support of the Ontario public, and now it had the force of law. With the appointment of the Reverend J.O.L. Spracklin as a Provincial Inspector in July 1920, the new law found a determined enforcer.

Yet, Spracklins appointment, and his three tumultuous months in office, would cast doubt on the wisdom of the government imposing goodness and temperance through force of arms. The attempt to impose Victorian controls by a militant clergyman would cause many to question whether religious beliefs had any place in Canadian legal codes. That this militancy could cost a man his life was proof that the crusade for moral reform had gone too far.

A Temperate Province

The events leading up to the confrontation between Spracklin and Trumble were part of the history of moral reform in Ontario, a long and complicated story with its roots in the human craving for alcohol.

Drinking was a way of life on the early Canadian frontier. Historian Fred Landon concluded that during its first fifty years as a province, Upper Canada, (later Ontario) must have been one of the least temperate countries in the world. Distilleries and breweries were proportionately as the gasoline stations of a more modern era and a cheap, bad whisky was everywhere available. Whisky, not low-alcohol beer, fueled frontier society. Patrick Shirreff, a Scottish traveler to Upper Canada in the 1830s was shocked at the prevalence of drunkenness, and that so many of his travelling companions were tipsy. Far more than long-settled Scotland, the Canadian frontier was dependent upon hard liquor. Taverns lined most thoroughfares and imbibers considered liquor a protection against impure water. At planting or harvest time, buckets of whisky went round among fieldhands and regular doses of grog warmed soldiers and sailors on duty Liquor was quite simply a dietary staple. Social gatherings such as barn raisings were fuelled by the free dispensation of liquor, and the wise builder kept back the offerings until the greater part of the structure was in place. In lieu of currency, liquor was often seen as a commodity, and after a harvest, a farmer could exchange grain for alcohol. Whisky would be served as a common household beverage and children would get used to its taste from infancy. It was apparent that During the pioneer period the constant consumption of alcoholic stimulants was widespread among all classes of inhabitants. Some of the clergy partook too freely of the beverage, and set an example which others were not slow to follow.