Contents

Guide

Page List

The Temple of Love at Untermyer Gardens has a prime view across the Hudson River, to fall colors and the cliffs of the Palisades

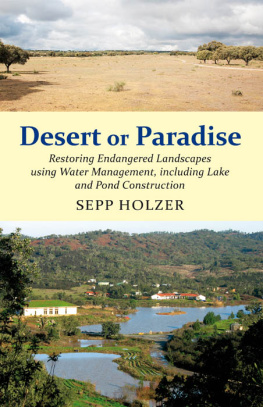

P ARADISE ON THE H UDSON

The CREATION, LOSS, and

REVIVAL of

a GREAT AMERICAN GARDEN

CAROLINE SEEBOHM

Hosta blooms and variegated Japanese forest grass are favorites in the restored garden.

CONTENTS

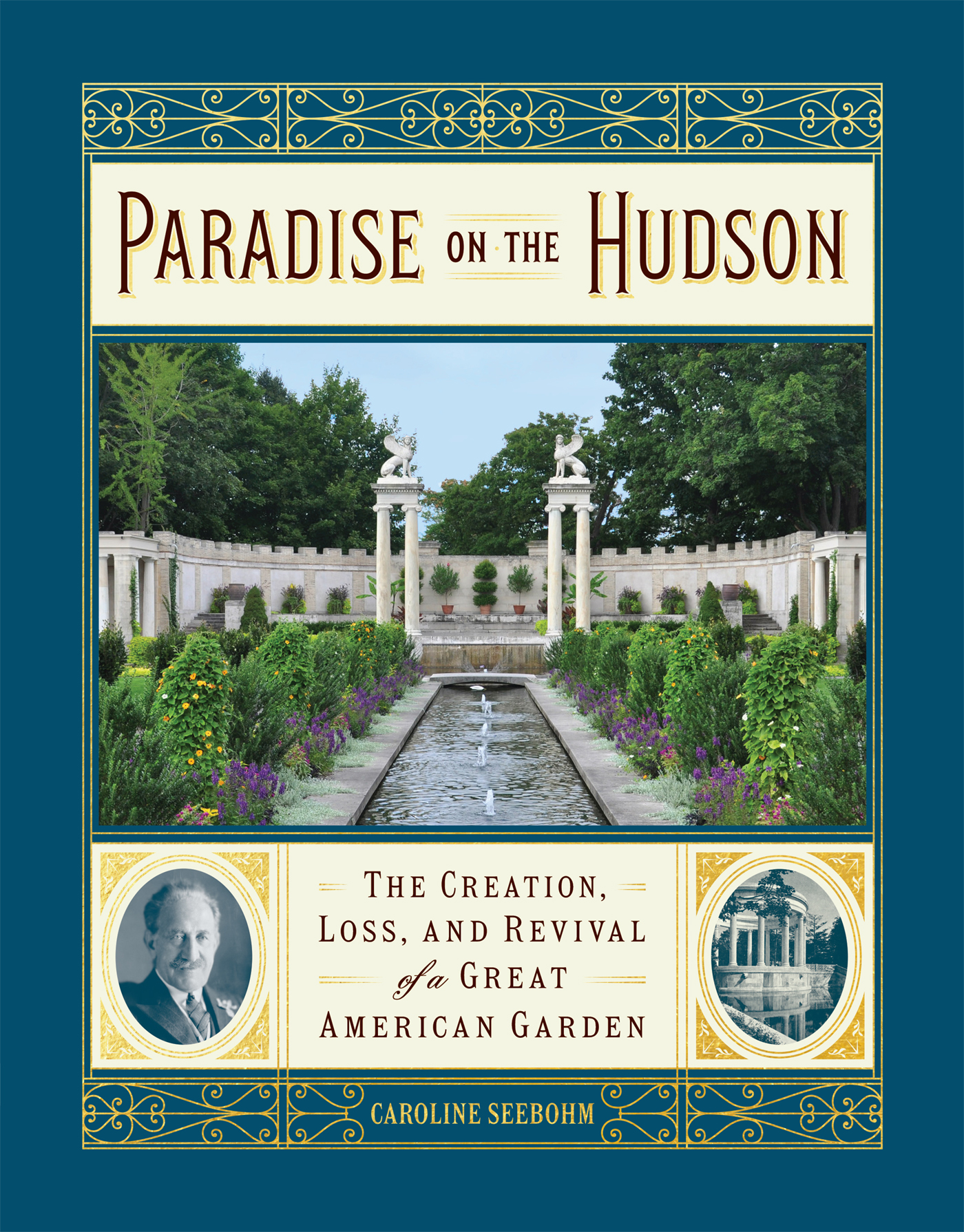

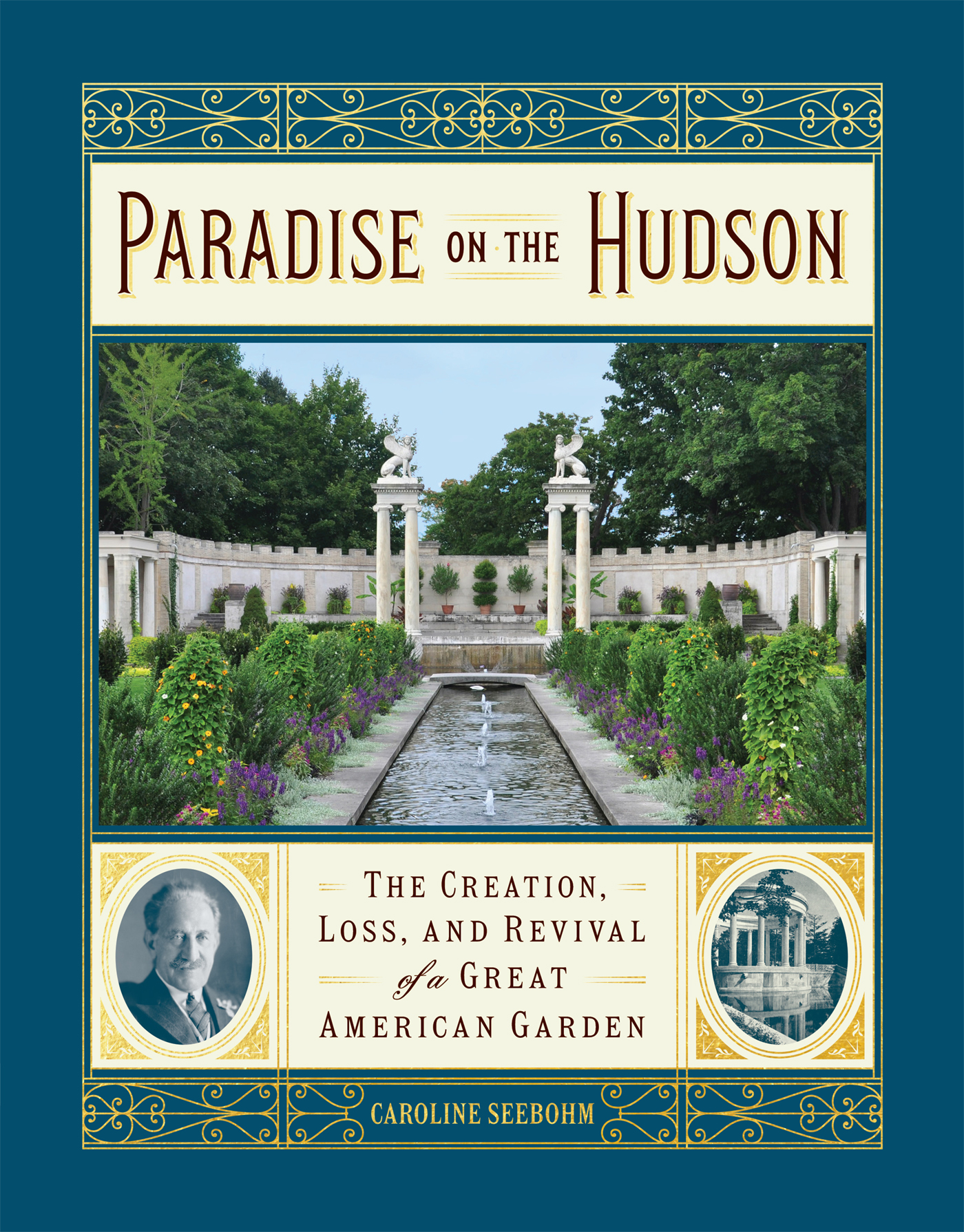

A main axis canal runs north-south in the Walled Garden, ending on the north end with the sphinxes and the amphitheater. The circular Temple of the Sky is to the west (left).

INTRODUCTION

In the early morning, with the mist rolling up from the river, you might think you have come upon the ruins of an ancient civilization: tall white pillars, Greek temples, a walled garden, an amphitheater, Moorish-style canals, stone-carved sphinxes, Chinese-like rock formations, twisting paths, crumbling walls, and a long staircase unfolding in a seemingly endless pale ribbon down to the water. Like a ghostly vision of paradise, the garden emerges, revealing everything and nothing. It seems unableyetto tell its secret.

This is the story of the making of that garden, and the man behind it. Both remain somewhat enigmatic to this day, extraordinary as it may seem in a time when so much information is at our fingertips. It harks back to different, more flamboyant times, and yet how reassuring it is in its confirmation of the power of the human spirit.

The garden came into being on the banks of the Hudson River, in Yonkers, New York. It was the brainchild of a brilliant, contentious millionaire, a Zionist Jew who married a Christian, a man who was a supporter of womens suffrage, a partner in the first and most successful Jewish law firm in New York, who advocated unpopular legal and financial reforms, and who very early foresaw the threat of Hitler. Married to a lover of art and music (his wife helped bring Gustav Mahler to New York), friend and supporter of Albert Einstein, this Democratic Party activist and celebrity lawyer also dreamed of creating a landscape that would bring the worlds of art, architecture, music, and horticulture together for the enjoyment of all.

Samuel Untermyer: ambitious, successful, and orchid-adorned New York attorney.

His name was Samuel Untermyer.

Who knows about this extraordinary New Yorker? His name is not in the pantheon of early twentieth-century titans such as Rockefeller, Morgan, or Carnegie; not inscribed on any library, hospital, or art museum in the city. Only a small fountain in Central Parks Conservatory Garden in New York bears his name. Yet his career touched on many of the great issues of the day, and he knew most of the major figures in local and national politics from the 1890s until his death in 1940.

Untermyer cultivated a fierce, take-no-prisoners technique that was generally put to use in support of progressive causes, including bank regulation and real estate racketeering. His clients included Hapsburgs, Ottoman sultans, ambassadors, movie moguls, newspaper barons, and celebrities.

The only idiosyncratic aspect of this fearsome man was his habit of wearing a fresh odontioda orchid in his buttonhole every day to court. Uncharacteristic, surely. A clue? Perhaps. For a completely different accomplishment plucked Samuel Untermyer out of this cutthroat world of social, legal, and political activism, immortalizing his name in another sphere entirely.

In 1899, Untermyer acquired Greystone, a turreted mansion and vast estate on the banks of the Hudson River. Like most wealthy property owners of the time, he envisaged a garden, and in 1916 he chose William Welles Bosworth to design it for him. Bosworth was a famous architect who had worked at Kykuit, the Rockefellers grand estate in Pocantico Hills, New York. Competitive as always, Untermyer demanded the finest garden in the world. Bosworth took his client at his word.

The result was beyond anyones wildest dreams. The design grew out of a vision of the Garden of Eden as described in the Book of Genesis. A walled garden was the first requirement, inspired by the great Persian and Islamic enclosed water gardens of the eighth to fifteenth centuries. Long canals represented the four ancient rivers, punctuated by small fountains and meeting at four central intersections. Octagonal towers marked the corners of the garden. An amphitheater dominated the far end, guarded by two sphinxes carved by Paul Manship, the premier American sculptor of the time. Overlooking the sweep of land going down to the river stood a Greek tempietto. In front of that, a swimming pool and lower terrace were decorated with ornamental tiles and mosaics.

The Temple of Love, a popular feature of Untermyer Gardens.

Leading away from the amphitheater, a modest doorway invited visitors to embark upon a spectacularly long and wide staircase down to the Hudson River. Two ancient and monolithic pillars framed the dramatic finale of the vista overlooking the Palisades, a twenty-mile stretch of exposed, steep cliffs on the west side of the Hudson River

Untermyer was a passionate plantsman, and Bosworth saw to it that his clients botanical desires were satisfied. Flower gardens were planted in the northern part of the landscape, each with a single colorquite revolutionary at a time when English-style, multicolored herbaceous borders were all the rage. Vegetable gardens and flowers shaded by pavilions flourished in beds and arbors farther down the slope toward the river bank.

No respectable garden at that time was complete without a folly, and Bosworth devised a delicate, Greek-style feature that was called the Temple of Love, sited at the top of a dizzying mount of rock formations, not unlike the naturally formed limestone rocks characteristic of early Chinese gardens. Waterfalls cascaded down these rocks into a pool below, the sound and movement creating a kind of