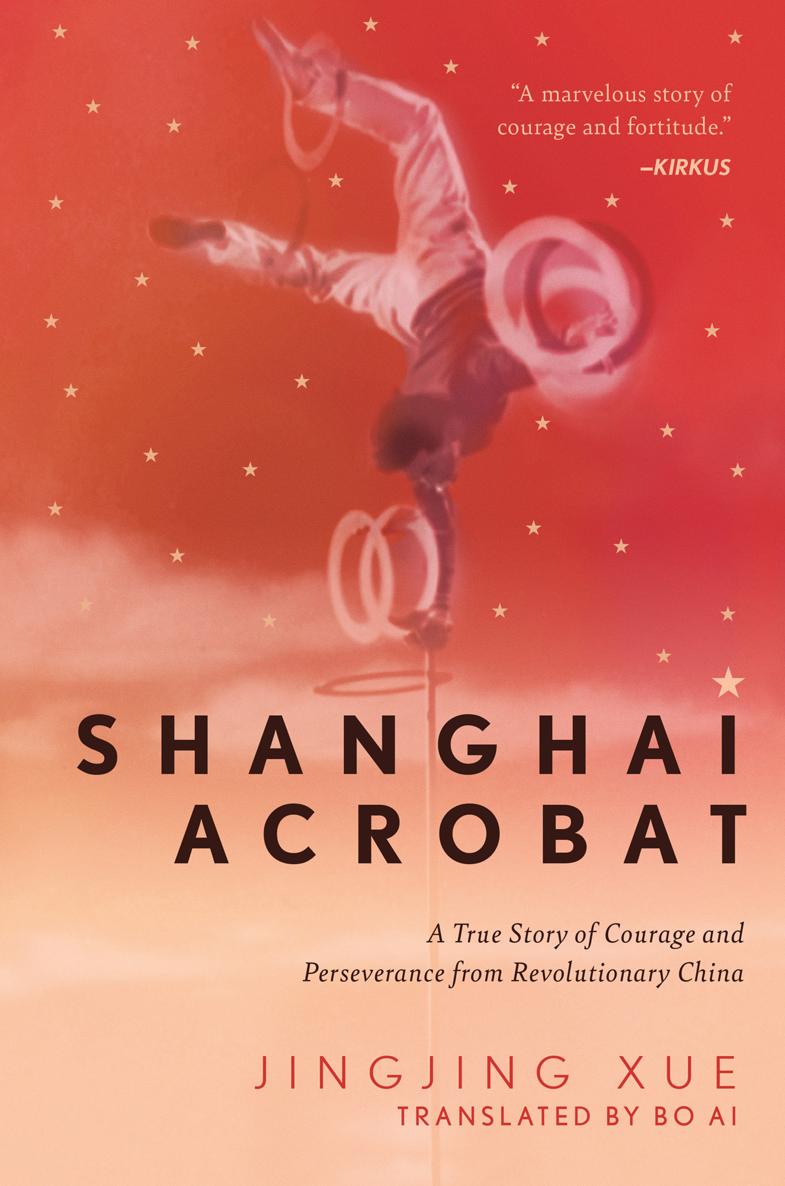

Shanghai Acrobat: A True Story of Courage and Perseverance from Revolutionary China

Copyright 2021 by Jingjing Xue and Malcolm Knox

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be sent by email to Apollo Publishers at info@apollopublishers.com. Apollo Publishers books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Special editions may be made available upon request. For details, contact Apollo Publishers at info@apollopublishers.com.

Visit our website at www.apollopublishers.com.

Translated from Chinese by Bo Ai.

Published by arrangement with Black, Inc.

Published in compliance with Californias Proposition 65.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020942965

Print ISBN: 978-1-948062-74-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-948062-75-6

Printed in the United States of America.

Prelude

In the ancient land of China there is a legend that, among all the animals who are born into this world, only humans cry. Every infant bears a birthmark on their back: the footprint of Yan Wang, the King of Hell, from when he forcefully kicked the child out into the world. Babies cry about the endless ocean of bitterness and suffering that awaits them there.

According to the legend, all people, wealthy or poor, noble or otherwise, have to endure lifelong suffering on their own. Some believe the legend and some dont, but it contains some of humankinds biggest philosophical questions: Where did I come from? What do I live for? Why am I here? Where am I going? What is the meaning of my life?

From infancy, we were told old legends such as this, all of which had some bearing on our modern lives. It was important to know our place, so another Chinese legend we learned was that humanity is divided into three types: those who are immovable, those who are movable and those who move on their own. Those who move invent theories, those who are movable propagate these theories and those who are immovable accept them. For thousands of years, the movers philosophers who ponder, explore and answer timeless questionshave set up their schools of thought. The movable help spread these philosophies. The immovable, baffled by all these ideas, can only find one explanation for what happens in their lives: destiny. Destiny can be neither altered nor foretold. It dictates our lives and cannot be controlled.

A humble soul in this vast universe, I was taught that I belong to the third class, the immovables. However, Im a little bit different. I believe there is destiny, but I refuse to succumb to it. Even though I am a lonely sailor on the endless ocean of suffering, faced with strong winds and huge waves, I sail persistently toward the far shore.

The Chosen

Y ou!... You!... Not you.... You!

The man was moving through the rows of students, coming toward me. I did not know whether I wanted him to choose me or not, as I had no idea where his decision might lead.

You!

He was getting closer. I shivered, but forced back the urge to stamp my feet. I was nine years old and this place, the Youth Village, was the fifth orphanage I had lived in. It was by far the worst. The classroom, where we were standing in lines waiting for this strange man to inspect us, was on the first floor of a red brick building facing west, receiving no sun until late in the dayand for most of the year. Sometimes, we children were allowed outside between classes to find a pool of sunlight to bathe in for a few precious minutes. Mostly, we froze in the below-freezing Shanghai temperatures. When it got too cold to bear, the older students would begin to stamp their feet and we would watch the teacher for his reaction. If he said nothing, we would all copy the older students. Once, in a rare show of sympathy, the teacher stopped the class and let us keep stamping until we warmed up.

You!

He was close to me now. All we had been told was that he had come from the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe, which was said to be famous, but I had no idea what an acrobatic troupe did, or what famous meant.

The man from the troupe, with one of our teachers beside him, stopped in front of me. He did not touch me, but merely swept his eyes over my body. I was the smallest child in the class. I had been an orphan since I was two years old.

You !

Three weeks passed before the man came back. In the meantime, we went about our normal routines in the Youth Village. The main building, a red brick former church, was our dining and meeting hall. Another red brick building, forming an L with the hall, contained dormitories for boys on the ground floor, with girls a floor above. My dormitory was jam-packed with bunk beds for more than twenty boys, from nine to sixteen years of age. The air was thick with smelly feet and farts. In the dining hall we ate plain flour noodles, cooked in soup with bran, pumpkins and carrots, without any trace of meat. Hunger was constant, as was constipation. Our hopes rose when the older boys wrote a petition to request better food, but nothing came of it. If those strong older boys could achieve nothing on such an essential matter, we were all powerless.

At the end of the L-shaped building complex, next to a wall connected to the main gate of the former church, was a dirt basketball court, where in the mornings we did exercises and at dusk we played. Sometimes we flew kites, and occasionally, against the wall of this court, there would be screenings of Russian war movies such as Lenin in October and Chapaev, the favorites of the older boys, who rushed to occupy the front rows. Those boys were like my big brothers and looked after me, but after everything I had been through already, I had developed a very independent character.

I had been chosen, but for what? While I waited to find out, I learned more about the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe. Before liberationthe word we were taught to use for the Communist revolution that had taken control of China seven years earlier, in 1949acrobats, or trick-players, were from the lowest stratum of society. Only those families who could not make a living would send their children to an acrobatic troupe to learn tricks, in the hope that they would have a trade to support themselves. After liberation, the status of acrobats sank even lower. Finding students became so difficult, the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe had to turn to the orphanages.