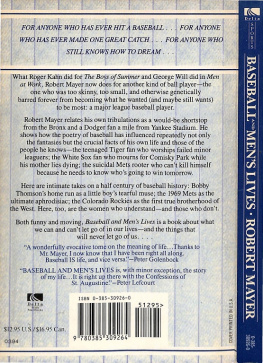

Robert Mayer - Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink

Here you can read online Robert Mayer - Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Robert Mayer: author's other books

Who wrote Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

W hen I was a kid my mother called me a skinny-marink. I never knew what a marink was, not then, not now, but skinny I certainly was, largely because whenever the Brooklyn Dodgers lost a baseball game I became too upset to eat. And the Dodgers lost a lot. Baseball, by the time I was seven years old, had lodged itself that deeply into my gut. My own national tapeworm. The Dodgers lost just often enough to keep my immigrant parents fearing for my survival. Such mounds of spaghetti and Yankee Doodles they did induce down my gullet I quickly burned off by playing ball from the moment school let out till half an hour past the time you could see the ball in your hand. There was a decided advantage to playing ball after dark; errors could be blamed on God, whod been dumb enough to invent the useless night.

Strictly speaking, it wasnt baseball that we played. I grew up in The Bronx, in a neighborhood of brick houses and tenements and narrow paved streets lined on both sides with parked cars. We played punchball in a concrete backyard that housed several garages; we played stickball in the street when the steady stream of traffic would allow. But as Humpty Dumpty would surely have instructed Alice, baseball we wanted it to be, and baseball it became, and anyone who says different is a liar. The fact that we used our fists or broomsticks instead of bats, that we hit Spaldeens or worn tennis balls instead of baseballs, never detracted from my

certainty that one day I would be playing in the major leagues. I would be the next Pee Wee Reese.

Though we lived a mile from Yankee Stadium, I seem to have emerged from the womb a Dodger fan. This was just as well, because the Yankees in that Joe DiMaggio-followed-by-Mickey Mantle era never seemed to lose; as a Yankee fan I might have become the Goodyear blimp. But rooting for the Yankees would have been like rooting for General Motors. I was congenitally for the underdog, an off-my-trolley Dodger. As was my older brother, for reasons equally obscure.

All my friends on the block were Yankee fans, and my infatuation with the Brooklyn Bums provided all the sweet music of childhood, the endless front-stoop arguments over who was better, Reese or Rizzuto, Mantle or Snider or Mays; all the grand cliches that got us through the wonder years, the true wonder yearsthe days when girls were that half of the human race who tried to throw a ball with the wrong foot in front. That and nothing more.

My earliest baseball memory is from the summer of 46, late at night, the Dodgers playing a night game with St. Louis, whom they were battling for the pennant that year, my parents and my brother asleep, me in my bed, seven years old, the blanket pulled over my head to hide the light of a flashlight and the sound of a portable radio, listening to the game. It was the top of the ninth, the Dodgers were losing, and a rookie catcher just called up from the minors was sent up to the plate to pinch-hit. It was his first major league at bat. He struck out, and the Dodgers lost. His name was Gil Hodges. You could look it up.

The Dodgers and the Cardinals tied for the pennant that year. They played the first play-off games in baseball history, best two out of three. The Dodgers lost. Bom to an ancient tribe of sufferers, I had found my baseball home. The next year the Dodgers, sparked by Jackie Robinson, would win the pennant but lose the World Series to the hated Yankees in the seventh game. The Bums Is Dead, the Daily News would proclaim, while my weight dropped precariously. They would lose the series to the Yankees again in 49. In 1950 they would fail to tie the Phillies for the

pennant on the final day, when Richie Ashburn would throw out Cal Abrams at home plate. I was eleven years old then and I still remember the name of the coach who sent Abrams in from third. Milton Stock. Mentioned prominently, I believe, in the Inferno---

And then came 1951.

Of 1951 we do not speak.

Through all of this we played our own games, countless boy hourspunchball, stickball, box ball, triangle. Punchball we played in the large backyard behind the houses our families rented. One side of the yard was formed by the windowless rear wall of a warehouse, solid brick. Another side was the solid brick wall of a tenement. Two sides were formed by the backs of brick houses, and these had windows in them. These windows, if left open, often caught our Spaldeens or tennis balls; we would have to beg to get them back; if left closed, when ball met glassa law of elementary physicsthe glass often broke. Mostly this happened to the bedroom window of Mrs. Newman, a frumpy haus-frau who would come waddling down to the backyard in pursuit of us, swinging a broom with which she hoped to box our ears. But there were two sloping cement driveways leading down to the yard, one at either end, and whichever Mrs. Newman chose to block with her huge bulk, we could always scamper up the other. The poor woman never understood Newtons third law of punch-ball dynamics: that a two-hundred-pound landlady in house slippers will never outrun a fifty-pound skinny-marink. Not ever.

Though I liked to be called Pee Wee, my nickname for one entire year was Slugger. That was because I was the only one on the block who couldnt punch the ball over the fence. But if there was derision in the name it was ill conceived. I had no desire to hit home runs: I was more the hit-and-run type, the slickest fielder in high-tops. Pathologically shy in school, on the ball field I was always the captain, shouting instructions to kids much older than I.

My mother, who did The New York Times crossword puzzle every day, was a firm believer in reading, and every two weeks we rode the trolley car together to the Fordham library. And every two weeks, to her chagrin, I came home with an armload of books about baseball. Fiction was dominated by the immortal John R. Tunis; the clackety-clackety-clack of spikes in The Kid from Tompkinsville and World Series wassince we ourselves played all our games in black high-top sneakerslike music from a foreign land. It was echoed in my childhood only by the clackety-clack of the trolley cars as they switched rails on the way to Fordham Road and the Grand Concourse, the Times Square of The Bronx. In the nonfiction section of the library I read every book available about how to play baseball. I studied as scrupulously as a brash young scientist at work. I knew the game. By the time I was eight years old I knew that on a hit to right field the shortstop had to cover second base, while on a hit to left field he had to go out for the relay. I knew that with a runner stealing and a left-hander at bat he had to cover second. I knew that to sacrifice a runner you squared around and caught the ball on the bat while laying down the bunt. And that bunting for a base hit was another matter entirely; hour after hour in the small front parlor of our apartment, where I slept, I stood with a bat in my hands and practiced dropping the bat on an imaginary ball, laying the ball down the third base line even as I broke toward first. I knew, therefore, nearly everything important about life. The only thing I didnt know was how to stop being afraid of the dark.

When I was six years old my brother took me one Saturday afternoon to see my very first movie, at the old Surrey Theater on Mount Eden Avenue, fourteen cents for kids. The attraction was an animated Walt Disney film called

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink»

Look at similar books to Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Baseball And Mens Lives: the true confessions of a skinny-marink and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.