Michelangelo

A Life on Paper

Michelangelo

A Life on Paper Leonard Barkan

Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barkan, Leonard.

Michelangelo : a life on paper / Leonard Barkan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Isbn 978-0-691-14766-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Michelangelo Buonarroti,

14751564Criticism and interpretation. 2. Michelangelo Buonarroti, 14751564Psychology. I. Michelangelo Buonarroti, 14751564. II. Title.

N6923.B9B345 2011

709.2dc22 2010007723

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Publication of this book has been aided by The Publication Fund, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, and Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

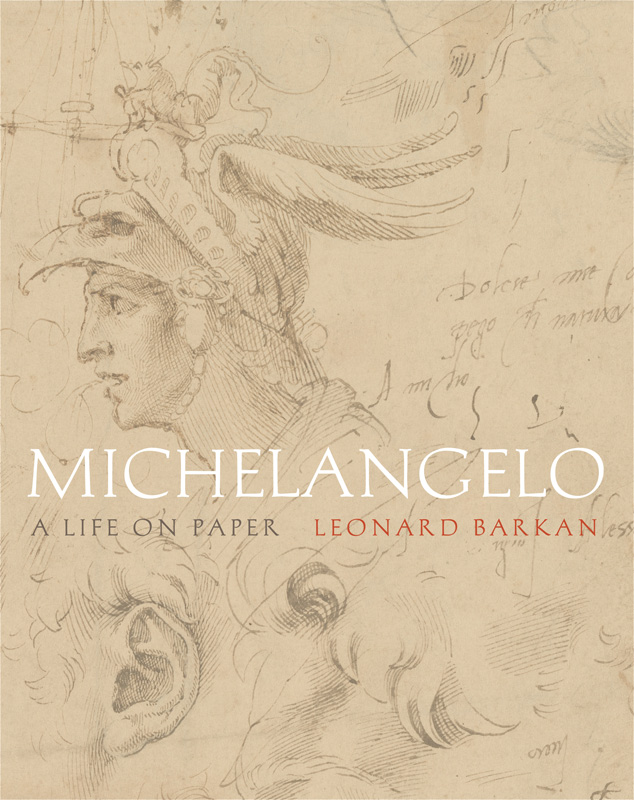

Frontispiece images: details from Michelangelo, Corpus 237v (p. i), Corpus 237r (p. ii), Ashmolean 45, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Ashmolean Museum

This book has been composed in Adobe Jenson Pro and Michelangelo BQ

Designed and composed by Tracy Baldwin

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in Italy

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Jon Koslow19512006

Preface

Michelangelo was a painter, a sculptor, and an architect. He was also a writerof poetry, of personal letters, and of countless memos detailing all the entrepreneurship that was required to produce large-scale masterpieces. The vast majority of those who have studied Michelangelo consider him as a visual artist; othersa smaller numberhave considered him as a poet. This book will argue that we cannot understand Michelangelo without a radical sense of the way that pictures and words entangled themselves within his creative imagination.

To the extent that this story has been told up to now, it has had to do with the fact that he wrote love poems with metaphors drawn from sculpture, or that his frescoes had their conceptual origins in the books he read, or that we can better understand his long career of unfinished monuments if we get to know his intentions by scanning his letters.

But this book attempts to locate the man in his full complexity on the pieces of paper that he covered with pen and brush strokes, with both words and images. Many have considered him the greatest draftsman who ever lived, and we are fortunate to possess some five or six hundred sheets with drawings generally agreed to be his authentic work. But it has not really been noticed before that a third of these drawings also contain text in his handwriting. Conversely, a quarter of the poems that we have in Michelangelos autograph make appearances on the same pieces of paper as do drawings. And as for personal letters and bookkeeping memos, a notable percentage are on sheets that he used, earlier or later, for doodles, sketches, and beautiful finished works.

On these surprisingly multi-functioning sheets of paper, we can find everything from the grandest expressions of his monumental genius to the most intimate messages to himself, we can read his ambition and his despair, we can watch him live out his eighty-nine years as they express themselves in layer upon layer of words and pictures.

Often, the combinations of materials on these sheets offer us a glimpse into a truly mysterious privacy. Considering that he intended most of these drawings for his eyes onlyin fact, he apparently did what he could, just before he died, to destroy many of them precisely because they represented too intimate a recordit comes as no surprise that they offer outward signs of a highly intriguing interior monologue. In one case, for instance, he draws two versions of a David statue and then inscribes next to them the enigmatic assertion, David with his slingshot and I with my bow, followed by a signature. At other times, he inserts in the narrow spaces between sketches fragmentary religious utterances (God, you are in man, in thought; Save me, O Lord, by thy name; sweet room in hell), or verses, apparently quoted from memory, like Gather them up at the foot of the wretched bush, from Dante, or Death is the end of a dark prison, from Petrarch.

One of the ways to map the artists inner territory of life and genius is to observe how frequently these sheets of paper are the sites where profoundly incongruent materials cohabit intimately. For example, one side of a sheet is devoted to a red chalk sketch depicting the Resurrection of Christ, while the other side is covered with careful notations of the moneys spent for chickens, oxen, clothing for two of his assistants, and funeral rites for his father. A beautiful drawing of a Madonna and Child is located next to a mock love poem that begins, You have a face sweeter than grape must, and it looks like a snail seems to have passed across it. On another sheet, Michelangelo inscribes a quatrain about Gods artistry on a spot whose obverse is occupied by the drawing of a horses rear end.

If some of the words amidst drawings are signs of the artists intimate self-conversation, others are signs that Michelangelos studio was also a place of society, where assistants, pupils, and patrons interacted with him. Thus, he writes Draw, Antonio, draw, and dont waste time to an assistant on a sheet where he has previously composed a beautiful Madonna, and the pupil in question has produced a ghastly copy right next to it. In another mood, and on a sheet where he and a different pupil have been drawing eyes, we read, Andrea, have patience; love me, sufficient consolation. Elsewhere, these communications have to do with artistic production itself. Under a gorgeously rendered version of the Fall of Phathon, Michelangelo hastily scribbles, If you dont like this sketch, let me know, so Ill have time to get another one done by tomorrow night; on a different page, next to some lovely projections for a triumphal arch, he writes, I dont have the courage because Im not an architect.

These examples are largely drawn from Michelangelos work as a visual artist who produced text, literally, in the margins. But it is equally significant that when he committed himself to poetrya calling he took more seriously than some have believedhe was also likely to intermingle alternative media of expression on a single sheet. Sometimes, the underlying interconnections are curiously logical: a sheet on which he writes a poem concerning the difficulties he has expressing his gratitude also contains the draft of a letter to the artist-biographer Giorgio Vasari reflecting the painful indebtedness Michelangelo felt for being dependent on Vasari for the building of the Laurentian Library, while next to the letter he has produced some tiny sketches of his preliminary ideas for the Librarys famous staircase. At other times, the connections are more difficult to plot: there is a sheet, for instance, on which we can trace his attempts to compose a poem concerning grief over the death of a loved one, but the writing is interrupted at a particularly painful moment in the metaphysical conceits of the verse; at this point, he apparently turns the sheet ninety degrees and produces a portrait of his own left hand, the index finger precisely touching the truncated problem spot in the rhyme.