SEAMS SEWN LONG AGO

The Story of Coats the Threadmakers

Brian Coats

Copyright 2013 Brian Coats

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1490408266

ISBN-13: 978-1490408262

In memory of my father,

Sir William Coats, and all

those who came before him.

For future generations,

so they can appreciate

their heritage.

Contents

Acknowledgements

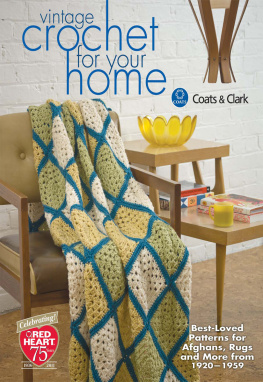

I would firstly like to thank all my colleagues and ex-colleagues who helped me to fill in the gaps in my knowledge of the company history. I much appreciate the time that many people took to send me interesting and amusing anecdotes about the company and particularly my father, few of which have found their way into the final text, but all of which I enjoyed immensely. I am also indebted to those at Coats who gave me access to the largely advertising material in the USA, which is where I started my research. One of the surprising things that emerged from this whole endeavor is the significant role that the USA played in the prosperity of what was after all a Scottish family and business. The company in England was very accommodating in showing me the material they have and in allowing me to use the spool label on the book cover. The old Chain logo on the title page is a trademark of J. & P. Coats and was also used with their kind permission.

Back in Scotland, the patience and perseverance of everyone at the Paisley Central Library was much appreciated. They helped me unearth some fascinating information I would never have found without their help. The Thread Mill Museum in Paisley was also an inspiration. They should be applauded for all the material they have preserved, much of which would have been lost without them. The net proceeds from the sale of this book will go to them.

Next on my list are the various members of the family whose support and knowledge were vital, particularly in piecing together the chapters on philanthropy, spending, and the Coatses who found fame outside the world of sewing thread.

I must mention several people by name: Christine McDerment painstakingly read, critiqued, and in the end improved my first version of the book; my son Andrew helped me design the cover and his partner, Leah Shesky, wrote the blurb; my daughter Julia was my first editor and her partner, John George, gave me legal advice; last, but by no means least, my wife Consuelo pushed me to get the book finished and showed infinite patience during the long hours of research and writing. For all that and so much more, she deserves the most special mention.

Prologue

The Origins of Sewing Thread

A thread will tie an honest man better than a chain a rogue.

Scottish proverb

To tell the Coats story, we must first delve into the distant past of the product that made the family pioneers rich and famous, sewing thread. For they were not inventing anything originalfar from it. Their fortune was made, as is so often the case, by being in the right place at the right time and having the intelligence, audacity, and organisation to exploit the situation to its fullest extent.

There is nothing new under the sun, and this is certainly true of thread. Yet any product that could even loosely be said to be sewable had to await the invention of a suitable needle. The earliest one with an eye, vaguely resembling the modern implement, is believed to have dated from about 40,000 years ago. The first definitive example came from the Solutrean culture, which existed in the Mcon district of eastern France between 19,000 and 15,000 BC. Their tools and techniques allowed them to fashion delicate slivers of flint to make light projectiles and even barbed arrowheads. By extension, they could also produce fine items like sewing needles, which were either made from sharp objects such as thorns or fish bones, or honed from ivory, bone, or horn.

Bronze needles appeared in 2,500 BC, in Crete and Egypt; iron ones date back to the third century BC in what is now Germany, and a complete set was also unearthed in a tomb in China from the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD), along with the earliest example yet found of a thimble.

Although the spinning of threads is a part of folklore and features in such famous childrens stories as Rumplestiltskin and The Sleeping Beauty , nobody can agree exactly where or when it started. Most scholars concur that it was over 10,000 years ago, and we can be sure that early ropes, sail cloth, bandages of Egyptian mummies, and tapestries all started in a spun form. It is theoretically possible to spin yarn without the aid of utensils, but hand-spun yarn was made using a distaff and drop spindle, and by the New Stone Age a spinner was capable of making about half a pound of yarn in a long, long day. The raw material was mostly linen, with sheeps wool being used towards the end of the period. The finished product was rough and uneven.

Clothing is even older than the needle and thread and was probably worn as far back as 100,000 BC. How do we know this? It is when the human body louse, which lodges in our clothing, first turned up. These clothes would have been animal skins or furs, combined with decorative shells and bones, and usually tied or draped. The earliest evidence of sewn skins is from over 30,000 years ago, which broadly matches the dating of the first needles.

The development of sewing thread is intimately related to that of embroidery. It is no coincidence that people attempted embroidery once the basic sewing tools were available, and recognisable forms date back to before 3,000 BC. Its introduction as an art form can be attributed to the Assyrians and Babylonians in biblical times, originating around 1500 BC. Their robes were intricately decorated with jewellery as well as woven and embroidered designs, and their interior textiles were elaborately patterned. No actual specimens have survived, but the Old Testament indicates that they had vivid colours, probably similar to those that evolved in Persia and Egypt. It is in the latter country that the earliest physical samples have been found, preserved thanks to the exceptionally dry climate. Their white-on-white needlework, used to decorate the fine linens of the Pharaohs, was marvelous.

It is impossible to explore the origins of embroidery or sewing thread without including silk, which developed in China and was shrouded in secrecy for as long as three millennia afterwards. Ancient legend gives the credit for its discovery to Lady Xi Ling Shi, the fourteen-year-old bride of the mythical Yellow Emperor, Huang Ti. According to Confucius, she was sitting in the garden one day, sipping from a cup of hot tea, when a silk cocoon fell in. The wispy fibers started to unwind in the steaming liquid, and in a flash of insight, she conceived the idea of unravelling them to spin into filaments, thus making a yarn. This is supposed to have taken place in 2640 BC. She is also credited with the introduction of silkworm breeding and the invention of the loom, presumably at some later date. Whether the story is true or not, the earliest examples of spun silk came from China at around this time, and she became the Goddess of Silk.

Silk production was introduced to Europe in 550 AD. Two Nestorian Monks smuggled silkworm eggs into Constantinople (now Istanbul) for the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I in their hollow bamboo walking sticks. They supervised the hatching of the eggs, the worms spun cocoons, and the Byzantine silk weaving mills were established. The Persians soon discovered the secret, so the Middle East began to compete successfully with the Chinese, but it would be another 600 years before Italy got in on the act, when 200 skilled Byzantine silk weavers were brought over at the time of the Second Crusades.