Contents

Preface

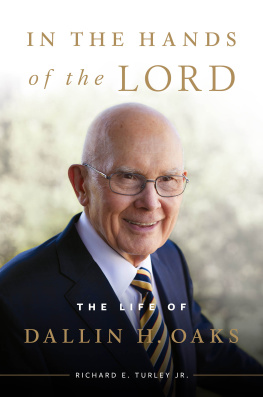

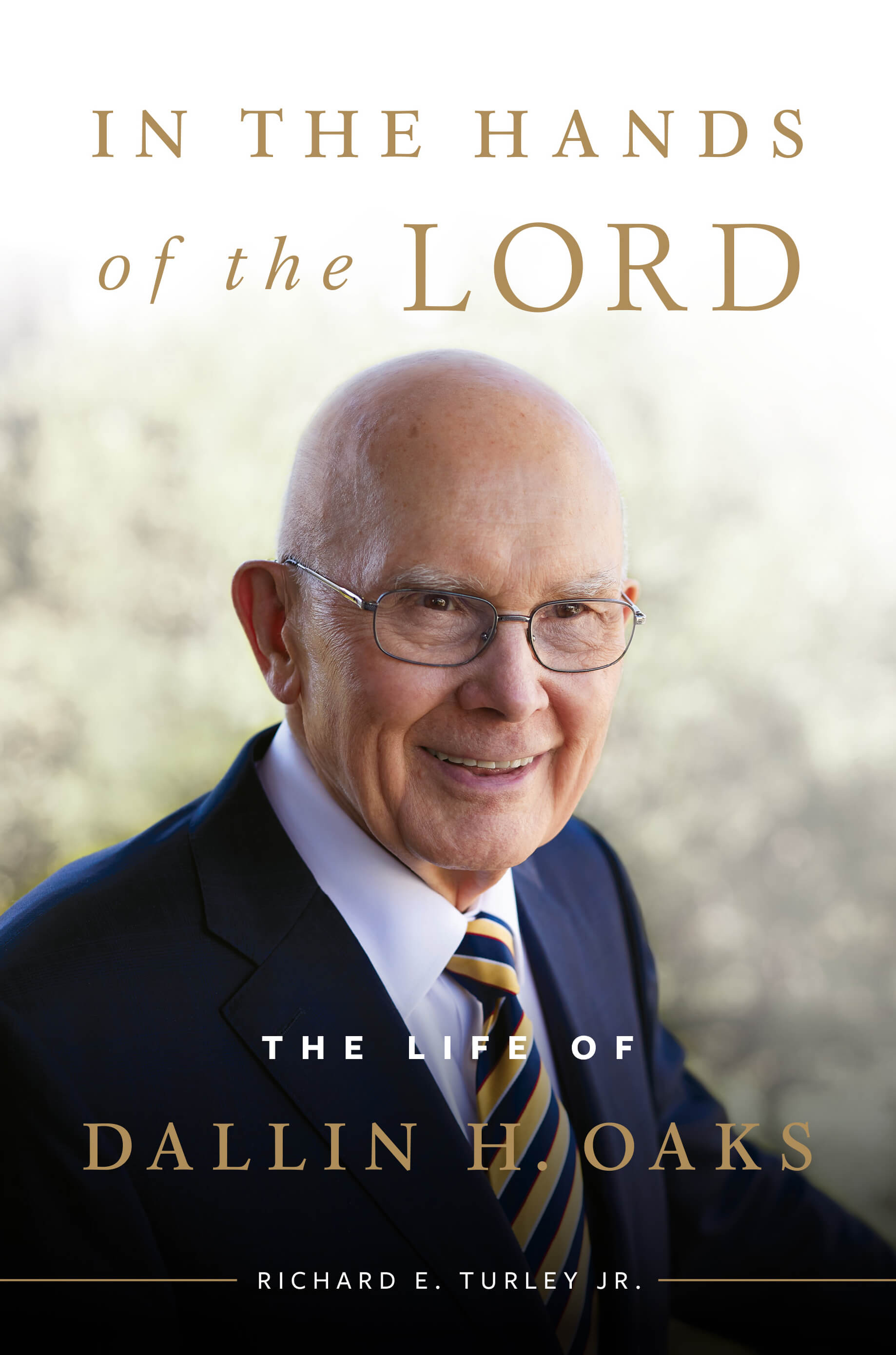

H aving known and worked with President Dallin H. Oaks most of my life, I felt honored when he asked me to write his biography. I admired him in my youth, attended Brigham Young University when he was president, saw him as a role model when I went to law school, and began working closely with him eight months after my graduation. In some ways, this biography is as much a product of my close observation as it is a distilling of sources documenting his life.

The sheer abundance of the documentary sources challenged me as a biographer. His life may be as well documented as any Latter-day Saint leaders in history. He was born to educated and literate parents who wrote about him when he was a child. He became a public figure as a radio personality in his youth and has remained in the public eye ever since. The range and depth of published and unpublished sources on his life will test anyone trying to be thorough in studying it.

When aiming at an academic audience, I have sometimes produced writings in which footnotes occupy half as much space as the text. When writing for the general audience to which this book is directed, however, I found such heavy documentation to be impractical for three reasons. First, full documentation would make the book exceed the size readers will buy or even choose to read. Second, most readers would rather have text than notes. Finally, some of the most important sources are not available to the public, making notes less valuable than they would otherwise be.

My initial drafts were heavily documented, and readers can be assured this biography rests on solid research. But to bring the manuscript within the contracted word count and keep the book from putting off readers, we chose to forgo citations to sources they could not access. Yet readers can often guess the source by keeping in mind that many quotations on President Oakss life up to 1980 come from a personal history he completed that year. That same year, he began keeping a journal in which he continues to write to this day, and many quotations from 1980 on come from it. As one who has read the journals of many General Authorities, from Joseph Smith to the present day, I consider Dallin H. Oakss to be among the very best. In addition, he has been a prodigious letter writer, and many passages in the text show they come from his correspondence. Finally, I was privileged to interview members of the First Presidency, Quorum of the Twelve, and other leaders for this biography, and when they are quoted without source citation, the quotations generally come from these interviews.

Two final points. Because of how seriously President Oaks takes his calling, he often appears in public to be sterna point on which family members rib him frequently. In private, he is warm, jovial, caring, and kind, with a winning smile. Few people I have known tell humorous stories with greater skill and relish. I have worked to capture both sides of him in this book. But when it comes to matters of principle, he is the same in public and private. He practices what he preaches.

Richard E. Turley Jr.

May 25, 2020

Chapter 1

Faith and Assurance

Birth and Childhood

T here was no hospital in Provo in 1932, and the Crane Maternity Home was having epidemic difficulties, explained Stella Harris Oaks of the circumstances when her pregnancy reached full term on August 12 that year. So the decision was made that our first baby would be born at homein the same room in which I had been born just twenty-six years previously.

Stellas water broke two weeks earlier, meaning this would be a dry birth, increasing the risk of complications. Yet with characteristic cheerfulness, she faced the long, painful labor bravely. After all, she was attended by four medical professionals: her husband of three years, Dr. Lloyd E. Oaks; his older brother Weston, with whom he practiced medicine; their sister Nettie H. Oaks, a newly graduated nurse; and Dr. Lloyd L. Cullimore, a general practitioner who came to Provo originally under a new federal program to reduce maternal and infant mortality.

They surrounded me, all in white, and eager to make things as easy for me as possible, Stella recounted. In their eagerness, however, they used a new, very effective anesthetic... so effective that it penetrated and numbed the newly birthing baby, too, so that he did not breathe upon delivery.

Trying to resuscitate the infant boy, the three doctors each took a turn exercising the tiny body of the baby, spatting him, bending him double, and trying every technique known to be effective, Stella remembered. Still, he did not respond. Finally, Nettie, standing tensely nearby, was suddenly and distinctly prompted to pick up a can of chloroform and spray his upper torso. The sudden freezing cold sensation caused him to gasp for that first precious breath.

Stella saw Netties prompting as a moment of inspiration that saved the childs life.

Stella had decided the boys name eighteen days earlier as she sat on a ditch bank in a public park in nearby Springville, Utah. Thousands had gathered for the unveiling of a statue dedicated to pioneer mothers by the Boston sculptor Cyrus Dallin. Hailing originally from Springville, Dallin had gone on to fame as the creator of iconic public sculptures, including the Angel Moroni atop the Salt Lake Temple, the Brigham Young monument at South Temple and Main Street in Salt Lake City, the Paul Revere statue near the Old North Church in Boston, and Appeal to the Great Spirit outside the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

As Stella Oaks watched Cyrus Dallin unveil his memorial to the pioneer women of Springville, topped by a bronze bust modeled after his own mother, she decided then and there to name her first child after the artistproviding it was a son.

That gave the newborn boy his first name, Dallin. His middle name, Harris, was Stellas maiden name. She was a great-granddaughter of Emer Harris, brother of Martin Harris, one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon, whose testimony appears in every edition of that volume of scripture. Giving the boy her maiden name would help him remember his mother and the history of his family and church.

Like my parents, who were both devoted members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Dallin Harris Oaks wrote years later, all of my ancestors have been members of the Restored Church since shortly after its organization in 1830. Most joined in the 1830s and 1840s, with the last entering the waters of baptism in 1855. All participated in the settlement of Utah in the pioneer period, coming to the state from 1847 through 1862. His ancestral roots were European: three-quarters English, an eighth Danish, and a sixteenth each Swedish and Irish.

Despite this sturdy ancestry, some of the Oaks family members worried about Stella and Lloyds firstborn son because of the long labor and the oxygen deprivation that occurred when he was born. As Stella later explained, It had been so long that evidently they were all just worried sick that he would not have his right mentality. She had not worried at all until her sister-in-law Jessie Oaks made a comment.

Suddenly filled with great worry and concern, Stella looked longingly toward the babys bassinet for some assurance that little Dallin was okay. His little hand waved, she recalled, and I will never forget it because I knew, I mean the Lord helped me know, that it was all right.

Though assured about his mental faculties, Stella strained under the burden of raising the boy, who experienced frequentsometimes constantphysical ailments. I remember the tears running down my face as I struggled in weakness to comfort the baby in the night as he screamed with colic, she wrote. Unfortunately, Dallins condition remained poor over the coming months. I was nearly broken in health from the long strain of the babys first year, Stella said. He had suffered almost daily of earache. It was rare indeed for him to sleep more than twenty minutes, and he always awakened screaming with pain. I did most of my work with him on my hip. I even learned to peel potatoes this way and sweep with one arm.