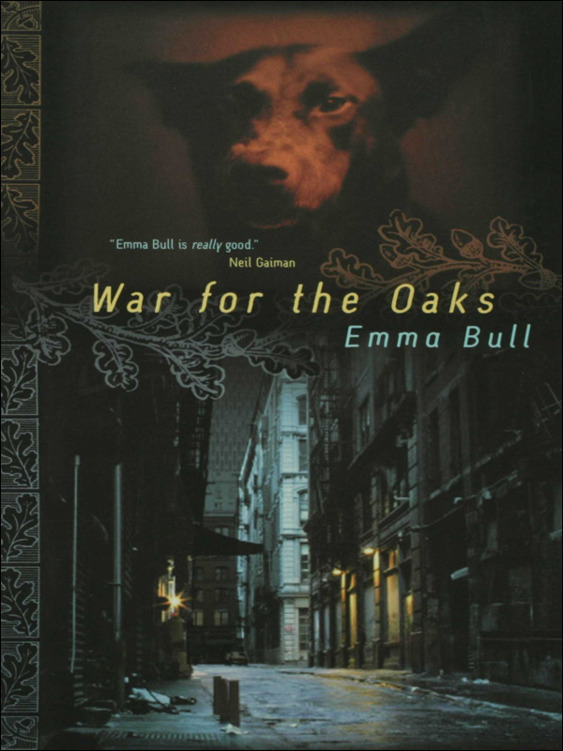

WAR FOR THE OAKS

Emma Bull

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.WAR FOR THE OAKSCopyright 1987, 2001 by Emma BullAll rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.Edited by Terri WindlingThis edition edited by Patrick Nielsen HaydenDesign by Jane Adele ReginaThis book was originally published by Ace Books, Berkley Publishing Group, in 1987.An Orb EditionPublished by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC175 Fifth AvenueNew York, NY 10010www.tor.comLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataBull, Emma, 1954 War for the Oaks / Emma Bull. p. cm. 1. Women rock musiciansFiction. 2. Minneapolis (Minn.)Fiction. 3. City and town lifeFiction. 4. Women SingersFiction. 5. FairiesFiction. I. Title.PS3552.U423 W37 2001813'. 54dc21

2001027117

0 9

This book is for my mother,

who knew right away that the Beatles were important,

and for my father, who never once complained about the noise.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are past due to Steven Brust, Nate Bucklin, Kara Dalkey, Pamela Dean, Pat Wrede, Cyn Horton, and Lois Bujold; they always want to know what happens next. Thanks also to Terri, who thought it was a good idea; Curt Quiner and Floyd Henderson, motorcycle gurus; Pamela and Lynda, for the cookies; Val, for comfort and threats; Mike, for the keyboards; and Knut-Koupe, for all the guitars.For the singin' and dancin': Boiled in Lead, Summer of Love, Ttes Noires, Curtiss A., Rue Nouveau, Paula Alexander, Prince and the Revolution, First Avenue, Seventh Street Entry, and the Uptown Bar.But most of all, to Will, for the whole shebang.

Contents

On the Folly of Introductions

Ideally, works of fiction don't need to be explained. When I see one of those scholarly and well-crafted essays that always seem to precede a volume of Jane Austen or Dorothy Parker, I skip it. Yes, I do. If it looks promising, I come back and read it when I'm done with the fiction. But I'd rather not know beforehand that a character is based on the author's brother, or that the author had just been cruelly rejected by his childhood sweetheart when he began . I like biography; but Charlotte Bront isn't Jane Eyre, and Louisa Alcott isn't Jo March, and I don't want to be lured into thinking otherwise if the author doesn't want me to.

I wonder sometimes how authors would feel if they read the introductions that spring up in front of their works after they're too dead to say anything about them. What if that character had nothing to do with the author's brother but was actually based on the writer's dad's stories about what it was like to grow up with Uncle Oscar? What if the author was rejected by his childhood sweetheart, but it was secretly something of a relief to him by that point, though he never said so to anyone? And does read differently if the reader knows that?

It's all just too darn risky, this business of introductions. If I weren't me, I'm sure I'd be working up to declaring here that "Bull's experience as a professional musician clearly informed War for the Oaks." But since I am me, I get to dodge that bullet. I'd had very little experience as a professional musician when I wrote this book. I was extrapolating from things I'd seen other people do, things I'd read and heard. War for the Oaks was written from the backside of the monitor speakers, as it were, and it wasn't until after the book was published and Cats Laughing came together (Adam Stemple, Lojo Russo, Bill Colsher, Steve Brust, and me, playing original electric folk/jazz/space music) that the novel became at all autobiographical. (By the time I became half of the goth-folk duo the Flash Girls, I was pretty used to the involvement of supernatural forces in one's band. Half kidding.)

But just knowing a few facts about the chronology of the author's life doesn't make introduction-writing safe. Writing a novel may be much like childbirth: once the end product's age is measured in double digits, the painful and messy details of its origin are a little fuzzy. My firstborn book is a teenager, and its very existence makes it hard for me to remember what life was like before it existed.

And as with teenagers, there's a point at which your book leaves the nest. What War for the Oaks means to me matters less, now that it's done and out of my hands, than what it means to whoever's reading it. A book makes intimate friends with people its author will never meet. I'm not part of those people's lives; Eddi McCandry is, and the Phouka, and Willy Silver, and the Queen of Air and Darkness. How can I describe or explain that relationship, when I'm not there to see it?

Here's what I can safely, honestly tell you about the story that follows this introduction: I still love this book.

I still believe in the things it says. When someone tells me, "War for the Oaks is one of my favorite books," it still makes me happy and proud.

Those are things only I could tell you; no writer of introductions, no matter how insightful, could deduce them from the text of the novel or the details of my life. But for everything else, the novel can, and should, speak for itself, and your relationship with it is as true as anyone else's, including mine. All I can do now is step aside and say, "I'd like you to meet my story."I hope the two of you hit it off.

Los Angeles

November 2000

Prologue

By day, the Nicollet Mall winds through Minneapolis like a paved canal. People flow between its banks, eddying at the doors of office towers and department stores. The big red-and-white city buses roar at every corner. On the many-globed lampposts, banners advertising a museum exhibit flap in the wind that the tallest buildings snatch out of the sky. The skyway system vaults the mall with its covered bridges of steel and glass, and they, too, are full of people, color, motion.But late at night, there's a change in the Nicollet Mall.The street lamp globes hang like myriad moons, and light glows in the empty bus shelters like nebulae. Down through the silent business district the mall twists, the silver zipper in a patchwork coat of many dark colors. The sound of traffic from Hennepin Avenue, one block over, might be the grating of the World-Worm's scales over stone.Near the south end of the mall, in front of Orchestra Hall, Peavey Plaza beckons: a reflecting pool, and a cascade that descends from towering chrome cylinders to a sunken walk-in maze of stone blocks and pillars for which "fountain" is an inadequate name. In the moonlight, it is black and silver, gray and white, full of an elusive play of shape and contrast.On that night, there were voices in Peavey Plaza. One was like the susurrus of the fountain itself, sometimes hissing, sometimes with the little-bell sound of a water drop striking. The other was deep and rough; if the concrete were an animal, it would have this voice."Tell me," said the water voice, "what you have found."The deep voice replied. "There is a woman who will do, I think."When water hits a hot griddle, it sizzles; the water-voice sounded like that. "You are our eyes and legs in this, Dog. That should not interfere with your tongue. Tell me!"A low, growling laugh, then: "She makes music, the kind that moves heart and body. In another time, we would have found her long before, for that alone. We grow fat and slow in this easy life," the rough voice said, as if it meant to say something very different.The water made a fierce sound, but the rough voice laughed again, and went on. "She is like flowering moss, delicate and fair, but proof against frosts and trampling feet. Her hair is the color of an elm leaf before it falls, her eyes the gray of the storm that brings it down. She does not offend the eye. She seems strong enough, and I think she is clever. Shall I bring her to show to you?""Can you?""B'lieve I can. But we should rather askwill she do what she's to do?"The water-voice's laughter was like sleet on a window. "With all the Court against her if she refuses? Oh, if we fancy her, Dog, she'll do. Pity her if she tries to stand against us."And the rough voice said quietly, "I shall."