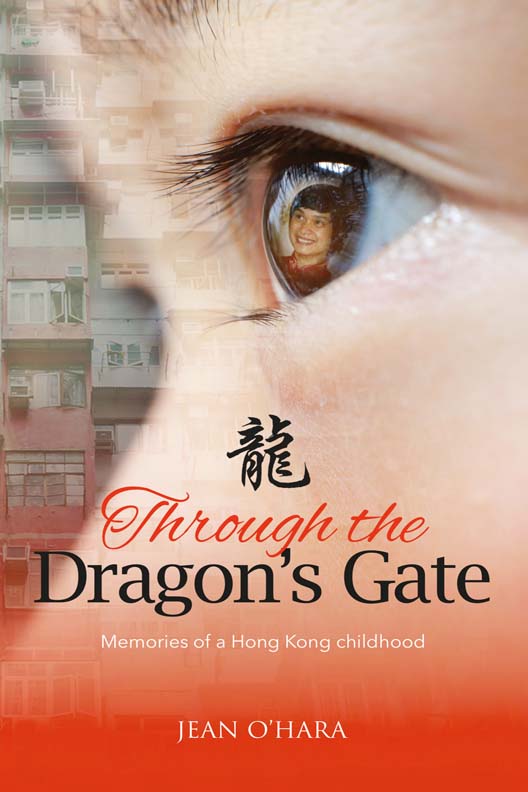

Through the Dragons Gate

Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood

Jean OHara

Copyright 2017 by Jean OHara

Jean OHara has asserted her right under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Published by Mereo

Mereo is an imprint of Memoirs Publishing

25 Market Place, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 2NX, England

Tel: 01285 640485, Email:

www.memoirspublishing.com or www.mereobooks.com

Read all about us at www.memoirspublishing.com .

See more about book writing on our blog www.bookwriting.co .

Follow us on twitter.com/memoirs books

Or twitter.com/MereoBooks

Join us on facebook.com/MemoirsPublishing

Or facebook.com/MereoBooks

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover, other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN: 978-1-86151-738-8

CONTENTS

Dedication

To my family, who have given so much to make this journey possible; to my husband, who has walked beside me; to the many patients I have met along the way; and to those who have inspired me. To Jamie and Heather, with all my love. This memoir is written for you and dedicated to my grandmother; and for Sara because I promised.

Acknowledgements

In researching for this memoir I have drawn on: The Fall of Hong Kong by Philip Snow; The Heritage Hikers Guide to Hong Kong , by Pete Spurrier; A Visitors Guide to Historic Hong Kong , by Sally Rodwell; and Fragments of the Past , by Randolph OHara.

All descriptions of clinical encounters have been anonymised. Where more detail is given, it is already in the public domain.

______

Early Days in Sheung Wan

The bamboo cane hung behind a thin partition door which did not reach the ceiling. Thin and flexible, it could slash through the air with such devastation that not even a childs cry could muffle the sound. That child seems many worlds away from the adult I have become. For several years into my adult life, the flesh on the backs of my thighs and buttocks vasodilated in an autonomic physiological response whenever I felt I had said something which might have provoked unintended anger or tension. The wheals it left in its wake healed quickly; the emotional self continues on a journey.

To be fair, caning was a reprimand used in many households and schools when I was growing up. But often I felt the punishment meted out to me was for a minor infringement; I would never have dared anything worse. I dont recall transgressions, apart from not turning down the volume on a television set one evening. We were sitting together, watching a television programme as a family. No one had asked me to turn the volume down, no one had said or even hinted that it was too loud; somehow I was just expected to know. The other reason would have been any hint of criticism in the end -of-term or yearly school report. This would be construed as unsatisfactory performance and in need of reprimand, but it did not happen often.

Sudden, inexplicable, incomprehensible bouts of danger or violence peppered my childhood. I remember being given a toy rifle for my birthday. I was a tomboy and enjoyed playing with such things. This rifle was very special. To my young mind it looked like the real thing, similar to those expertly handled by cowboys in the Wild West films of the 1950s, or by the US Marshall in the American television series Gunsmoke. I was thrilled. I had visions of lying in wait behind some boulder, for what was probably only minutes but felt like hours, as someone came into my field of vision and I would secretly, quietly, take them out with a gentle squeeze of the trigger. Then the shootout would begin. When I came to London to start medical school, one of the first extra-curricular clubs I joined was the rifle club. I didnt pursue it for long, finding the reality of lying in the rifle range not as satisfying as I had imagined, but I was a pretty good shot.

I also had recurrent dreams of flying, or running away. One day, probably in my pre-teens, I decided that if I was ever beaten again, or locked out of home, I would run away. Nothing was planned. It was just a promise I made to myself. Luckily I never needed to put my resolve to the test.

Perhaps it was because I was physically bigger and stronger and more independent, but I think it was actually because life at home got easier. We were no longer living hand to mouth, there was the promise of promotions with increased salaries and my father on the threshold of being eligible for a government-sponsored flat. I was 15.

Home before then was in the oldest part of Hong Kong island, the most traditional Chinese part where foreigners did not enter. Sheung Wan District was directly west of Central District, and during my early childhood my home street was very near the waterfront. It was named after Sir Samuel Bonham, governor of Hong Kong in the early 1850s. He brought trade into Queen Victorias new colony with American whaling ships calling in for supplies; it soon became the embarkation port for mainland China. Sheung Wan was a warren of streets and the hongs of Chinese trading, from rice, birds nest, dried seafood, tea and traditional medicines. We lived above a watch shop. Early in the morning I would hear the foghorns sound, and the rattle of carts going down the gentle sloping road outside. By day the streets would be thronged with the local Chinese going to nearby wet markets, street stalls, teahouses and small businesses. In the early evening there would likely be the sound of merriment as local youngsters played Chinese shuttlecock. By night, I would hear, and often smell, the weekly stench as night soil ladies came up the stairs to our landing to collect buckets of human excrement. We had very basic sanitation. Although we had running water, I also remember months of rationing during the Cultural Revolution, when older cousins who lived with us would join long queues to bring water home every few days.

Nothing remains of the street where I lived. At least, not the street of my childhood. It has been engulfed in a wave of expansion as small residential streets in the heart of an old Chinese neighbourhood give way to the sprawling concrete jungle of new office blocks, banks and even gleaming posh hotels and landscaped gardens, complete with statues and water fountains. When I was a child, one would not see a gweilo (foreign devil) walking the streets of my home. The Colonial elite merely passed by in their private cars, or rickshaws, on their way to pick up an artefact in the famous curio market of Cat Street, or on their way home in the affluent surroundings of the mid-levels or Victoria Peak. No gweilos would stop in the lanes and alleyways I called home. It was the haunt of the Chinese working class a village atmosphere where everyone knew their neighbours, and the streets were full of clatter as wooden carts tumbled down the road alongside the occasional motorized vehicle. The banter of warm greetings and the slamming of steel gates marked the beginning of another trading day, as shops opened for business.

In the afternoon, a lone flying olive pedlar often sauntered down the street in his kung fu slippers, carrying a satchel of preserved olives, and playing on the strings of his erhu (Chinese fiddle). When lucky enough to gain a ten cent coin from my grandmother, I would rush out onto our balcony, shout out what I wanted to buy and throw the money onto the pavement below. On pocketing payment, he would kick a small bag of olives, sending it flying up in the air to land on our balcony. He never missed.

Next page