DOUBLEDAY

Copyright 2010 by Leon Fleisher

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the DD colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

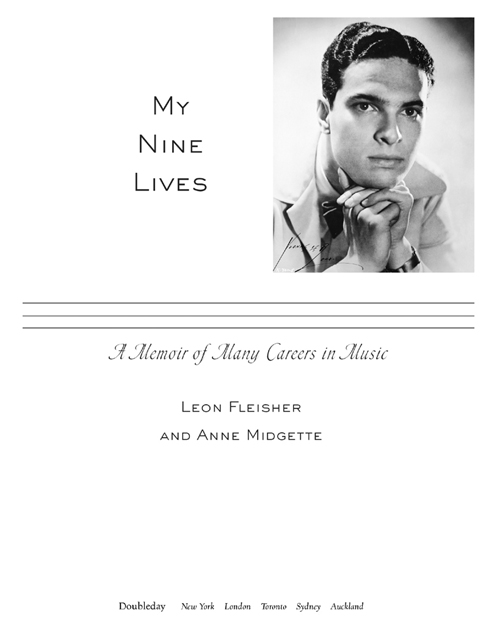

Title page photo: collection of Leon Fleisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fleisher, Leon.

My nine lives : a memoir of many careers in music /

Leon Fleisher and Anne Midgette.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Fleisher, Leon. 2. PianistsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Midgette, Anne. II. Title.

ML417.F56A3 2010

786.2092dc22

[B] 2010012735

eISBN: 978-0-385-53366-9

v3.1

To the memory of my father, Isidor Fleisher,

and my brother, Raymond Fleisher,

who made so many sacrifices so I could live these lives;

and my mother, Bertha Fleisher,

who dreamed of them first.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Child Prodigy

CHAPTER 2

Student of Schnabel

CHAPTER 3

Outstanding Young American Pianist

CHAPTER 4

The Bohemian

CHAPTER 5

The Young Lion

CHAPTER 6

Catastrophe

CHAPTER 7

The Conductor

CHAPTER 8

The Teacher

CHAPTER 9

The Left-Handed Pianist

CHAPTER 10

Renaissance Man

INTRODUCTION

My twelfth birthday present from my mother and father was a recording of Brahmss first piano concerto in D Minor. My family didnt have many records, apart from a few by Enrico Carusoa staple in American homes in those daysbut my parents knew this one was something out of the ordinary. The soloist was my teacher, the great Artur Schnabel, whose playing even then was legendary and bore the seal of absolute authority: after all, in his youth in Vienna he had met Brahms, and heard him play, and even gone on a picnic with him. And the conductor was the brilliant Hungarian taskmaster George Szell.

The Brahms D Minor concerto is a huge work. In those days of 78 rpm records, it took up seven or eight disks. I put the first disk on the record player and lowered the needle, and a dark roll of timpani poured out of the big horn of the speaker, like the thunder of Thor. There followed a defiant cry from the massed forces of the orchestra, as if shaking a fist at the lowering heavens. The hair on my head stood up. That opening did something to me that no other music had done before. I wore out the first side of that recording. It took me about a week even to get to side 2, where the piano actually makes its entrance.

For weeks I ate, slept, and breathed that piece. Even for a child prodigy, the Brahms D Minor is a tall order. It calls for two-fisted piano playing and emotions that you might think are beyond the compass of a child. But I loved it so much I couldnt stay away. Within a year or so, I was working on making it my own. I was probably a little young. Its smart, though, to learn very difficult repertory when youre young. That way, you get it in your fingers, and in your DNA, before you realize just how hard it really is.

From the moment I first heard it, I dreamed of playing the Brahms D Minor with a full orchestra, with George Szell conducting. And when I began learning it, actually playing it myself, I dreamed even harder. Dreaming helps. My dreams were fulfilled. The Brahms D Minor concerto became my talisman. I played it in my debut with the New York Philharmonic, when I was sixteen. I played it when I won the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels. And I played it, finally, with George Szell. We even recorded it together. Some people call our recording a classic.

If my story is about anything, its about being very careful when your dreams come true. The Greek myths are full of tales of heroes cut down in the arrogance of their prime, taught humility by a blow from the gods. It sounds melodramatic. But such things really can happen. They happened to me. I was at the peak of my career, ready to conquer the world, and whether or not I was guilty of hubris, the thunder of Thor came down and hit me where I lived. When I was thirty-six years old, I mysteriously lost the use of two fingers on my right hand. The fourth and fifth finger started cramping, curling up, until they were firmly lodged against my palm. When the gods want to get you, they know right where to strike: the place it will hurt the most. I thought I would never play again.

Was it in my head? Was it some bigger malady? No one was able to tell me what was wrong. I looked. I looked in more places than I might have thought possible. I was willing to try anything to get the use of my hand back: treatments, therapy, medications, spiritual healers, you name it.

I wasnt especially noble in my affliction. I shut down. I acted out in all kinds of ways, of which I am not particularly proud. Inwardly, I railed against my situation; outwardly, I hid from it, turning away from friends and family, trying to prove however I could that I was still vital. I grew my hair, grew out my beard, and began tooling around on a Vespa. I didnt have any other tools to help me deal with what had happened. It was hard to find words for the dark cloud that hovered over me: of anguish, of dejection, of rage. I fell into a deep depression. At my lowest point, I seriously considered killing myself.

But I didnt kill myself. I stayed alive. And, just as I was stuck with being alive, I was stuck with my love of music. Something about it was still sustaining, and still worthwhile. So I embarked on a quest to make a life in music, in any way I could.

I t wasnt the first time Id found myself setting out on a new career.

I always say Ive had more careers than a cat has lives. Even before I lost the use of my hand, my life with the piano never seemed to be a straightforward process. First, I was a child prodigy, playing Beethoven concertos in my native San Francisco; but that ended when Schnabel himself took me on as a student, on the condition that I give no more concerts. After years of study with him, I was ready to take the world by storm after my New York Philharmonic debut at sixteen, but after a couple of years of concert activity, the engagements seemed to peter out. Not until I became the first American to win the prestigious Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, at twenty-three, did I develop a piano career that had staying power. Then came the disaster with my hand, and it seemed that chapter was over.

But after the catastrophe, I slowly found my way to other careers in music. I became a conductor, working with other musicians to make the sounds I could no longer make myself. I developed as a teacher, learning to use words to communicate the truths in the pieces I loved, which I had once expressed with my fingers alone. Somehow, my experience of music became richer the more I explored other ways of relating to it.

I didnt fully realize, as I lived them, how much these different careers were opening me up to new experiences and approaches I had never even dreamed of. I, the clean-cut piano soloist, took on the appearance of a long-haired hippie. I, the interpreter of Brahms, began conducting contemporary music that was unlike anything I had previously encountered in my musical life: thorny scores and avant-garde operas. I, the hard-nosed rationalist who spent hours a day sitting at the piano practicing, began visiting faith healers, practitioners of Eastern medicine, gurus, and quacks, in search of a cure. I, the acolyte of the great Schnabel, began seeking out other piano teachers and experimenting with different techniques to see if anything could cast some light on my condition.