A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

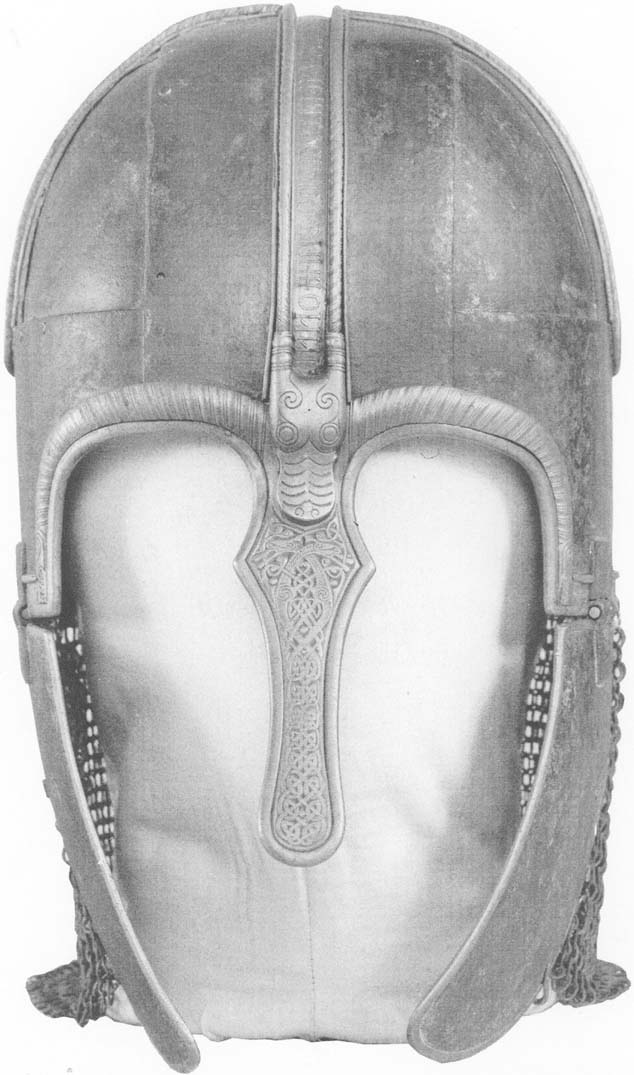

I am grateful to all who assisted in compiling this volume. Firstly, Angela C Evans, Curator of the Sutton Hoo collections and the Department of Prehistory and Europe at the British Museum, for her stimulating introduction to the Sutton Hoo Collection. To Barry Ager, also a curator of the Department of Prehistory and Europe, for giving me the opportunity to research Germanic Migration period swords; the rare privilege of detailed study of highly significant and complex Frankish throwing axes and, subsequently, a large seax collection. During these researches Barry periodically provided useful and thought-provoking suggestions on weapon problems and feasible technical advice. I am grateful to Virginia Smithson, departmental information officer, for providing an organized working base in the study room. I am also thankful to Ms Sovati Louden-Smith for her efficient, punctilious assistance in ordering numerous photographs.

For revealing comments on weapons in the prehistoric period, and for his very useful advice on arms, particularly on swords of the late Bronze and early Iron Ages, I am most grateful to Jonathan Cotton, Curator, Prehistory Department of Early London History and Collections at the Museum of London

I should like to thank Paul Hill, a most helpful and knowledgeable friend and colleague, with whom I undertook several joint weapon studies. These included Germanic Migration period swords from the pagan cemetery at Mitcham and a later, larger analysis of weapons and protective accoutrements recovered by Wessex Archaeology from the Saxon cemetery at Park Lane in Croydon. I am most grateful to Paul for his periodic assistance with this book, and especially for contributing the excellent , on Anglo-Saxon and Viking period spears.

I extend sincere thanks to John Eagle, the well-known military lecturer on the Roman army, for providing numerous accurate and, above all, realistic and exciting, illustrations featuring live action figures.

I am indebted to Elizabeth Hartley, Curator of Archaeology at the Yorkshire Museum, for allowing me to quote from the paper A Late Anglo-Saxon Sword from Gilling West, N. Yorkshire, which describes this significant weapon and its discovery. I am also most grateful to Professor John Hines, editor of Medieval Archaeology vol. XXX, 1986, published by the Society of Medieval Archaeology, for his kind permission to reproduce the fascinating technical drawings and to publish the informative blade paper written by Dr Brian J Gilmour.

Finally, I am particularly grateful to Professor Vera I Evison for permitting me to publish verbatim two sections from her enlightening paper A Sword from the Thames at Wallingford Bridge. I am also indebted to her for granting permission to reproduce her drawing of the late Saxon sword from the Thames found in 1840. The professors article contributes markedly to a better and quicker understanding of the development and typology of English swords from the second half of the 9th century to the early 11th century. I strongly recommend her paper to those researching swords of this period.

is a brief introductory study of the flint, copper, bronze and early iron weapons of prehistory. Thereafter, the work concentrates in great detail on weapons of the early Germanic period in Britain (a time for which, until recently, little in terms of weapon usage was understood) and continues with study of those of the Angles, Saxons, Franks, Vikings and the English during the 8th to the early 11th century. Examination of 11th century Norman weapons is included. The Viking chapter explains the reasons for the considerable increase of sword usage during this period, the complex Viking swordhilt typology, and major technical sword-manufacturing changes.

I have undertaken detailed research since 1998 on 5th to late 9th century weapon collections in London and county museums. During this process I developed some new interpretations of Dark Age weapon handling and usage while attempting to formulate more plausible, wider theories concerning their use. I was compelled to adopt a new, special blade-measuring system due to the scarcity of surviving hilt components. This, rather surprisingly, actually proved most enlightening and useful. Until the works of Ewart Oakeshott and Hilda Ellis Davidson in the 1960s, and the papers of Vera I Evison, in particular her authorative work, A Sword from the Thames at Wallingford Bridge, little work had been done on the nature of weapon employment in antiquity. Much has been written on morphology and some work had been attempted on typologies. However, there is much to be said about the combat advantages and disadvantages of ancient arms and their performance in battle and I shall do so here. Where necessary this includes minor amendments to existing typologies.

It is difficult to be sure who wielded the first weapons in Britain, or what sort of arms they were, but it is true to say that, certainly by the neolithic period, warfare was widely employed, and evidence for it can be seen from excavations such as those at Crickley Hill and Cam Brae.

The former site, in Gloucestershire, was an undefended causeway enclosure that received an attack from an enemy armed predominantly with bows. The subsequent rebuilding of the site with a huge breastwork of ditch and rampart was clearly designed to keep such invaders out. The main point about modern excavations at this site is that they show warfare on a grand scale with defensive works and thousands of arrowheads within the perimeter. Crickley Hill was attacked at least twice in its long history. The indications are that whoever was doing the attacking was using missile weapons and was well organized.