Contents

There is hardly a single action we perform in that phase [adolescence, early manhood] which we would not give anything, in later life, to be able to annul.

Marcel Proust, Within

A Budding Grove

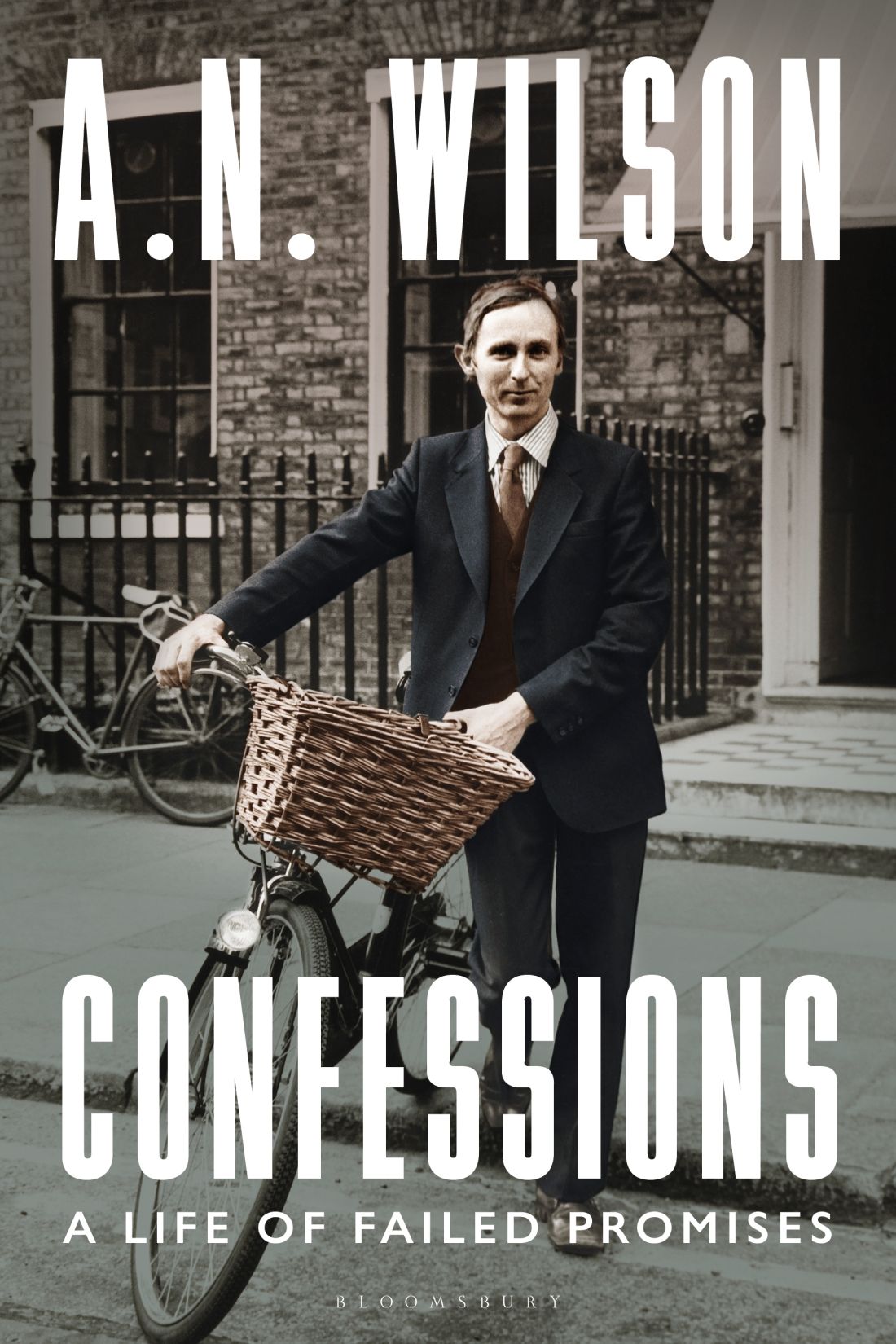

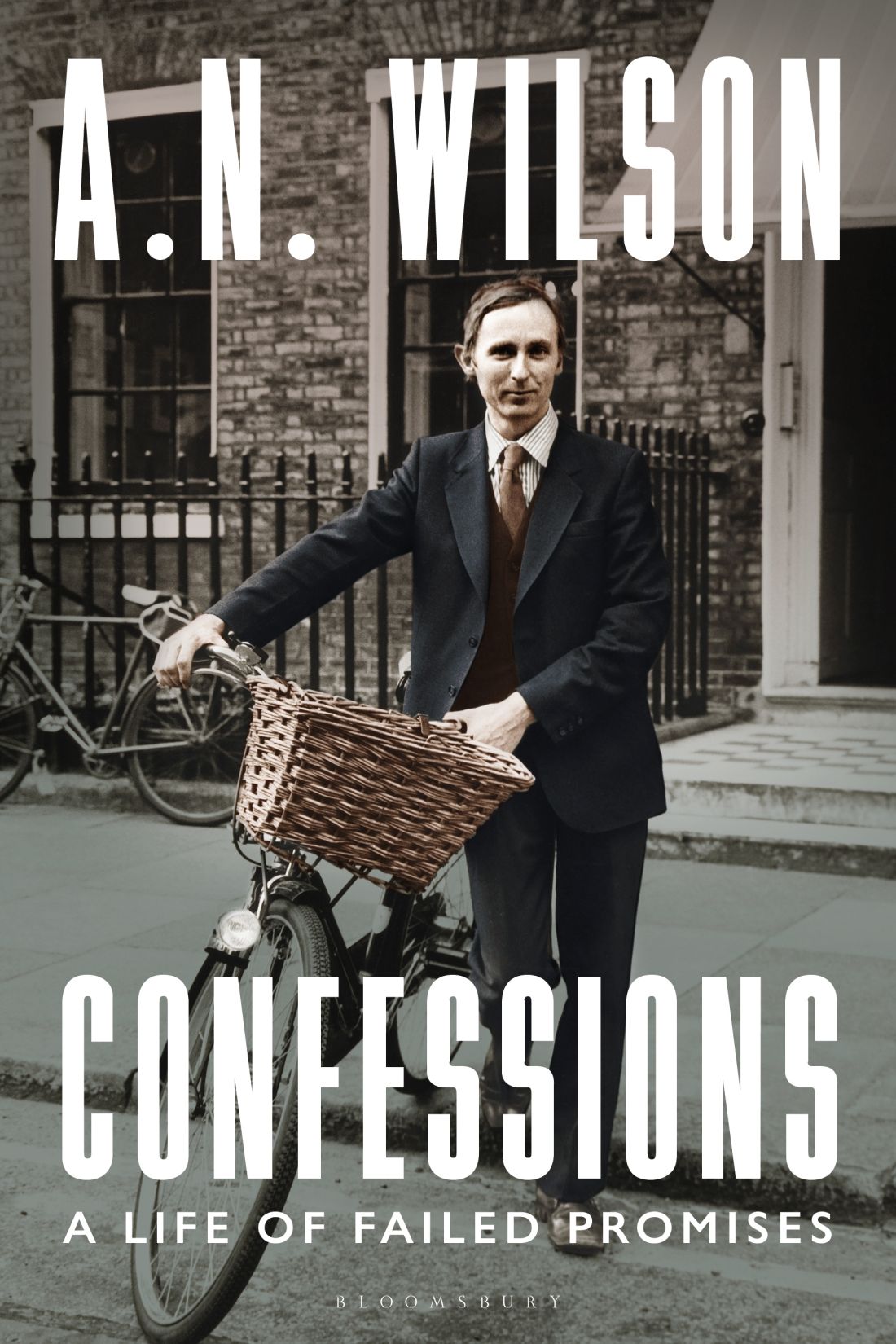

All my life I have been a writer. Long before I first published a book, in my early twenties, I had formed the habit of putting experiences into written words trying to learn to use words, as T. S. Eliot calls this strange activity. Those who have been kind enough, over the years, to tell me that they have enjoyed one of my novels, or something I wrote in a newspaper, or a biography, would probably be surprised that the finished product was a result to quote from the same poem (East Coker) of the intolerable wrestle / With words and meanings. Fans and hostile critics alike have always spoken to, and of, me as one who was too fluent, who wrote with too much ease. Over fifty books published, and probably millions of words in the newspapers.

A young sub on an English newspaper once guilelessly asked his legendarily terrifying editor, Why are we giving so much money to that A. N. Wilson for something hes obviously just dashed off in half an hour? The reply, flattering to me, was Because he CAN dash off the f**king article in half an hour something that would take others the whole f**king day.

Inevitably, this facility has led me to write what has sometimes been deemed too much. My difficulty with writing, with the business of trying to learn to use words, has not been in the act itself. I have never suffered from writers block. Rather, my problem has been trying to match the words to the truth of experience, whether I was composing a fiction, writing a work of history or biography, or keeping up my highly addictive work in the newspapers. (At one point, in the 1990s, I was writing three regular newspaper columns a week, as well as writing some of my longest historical works, such as The Victorians and its sequels, and publishing a novel every other year.)

To read the great writers is to be hit, in any number of ways, by their authenticity: they have recreated a scene, a character, in the perfect form of words for that purpose. Theyve scored a bullseye. This is what one is aiming for. Most printed words that we scan from week to week, or year to year, fail to hit the mark. They are newspaper articles that utterly fail to describe an event; they are slipshod biographies or unsuccessful novels. Then you come across the great writers, and you have struck gold.

Reading has always been a bigger part of my life than writing, and what I owe to the great writers of the past will sometimes be mentioned in this book. Our relationship with our favourite writers is deeper than many of our friendships with living people. For some reason, I have always been lucky enough to have time to read. So many of those I know either read for half an hour at the end of the day or reserve reading for long flights. I read constantly, and to deprive me of books would be the worst possible torture.

Through all the frantic rush of my own writing life I have had at the back of my mind the high standards set by my favourite writers, and the awareness that I was failing, over and over again, to live up to such standards. Jane Austen spoke, on her final birthday (her forty-first), of her work as the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush. But, although I revere her this side of idolatry, that has never been the kind of writer I aspired to be, or could have been.

This book takes me up to the point where I had decided that I wanted, in my mid-thirties, to write the biography of Tolstoy. Of course, I am not worthy to lick the boots of either Jane Austen or Tolstoy, but I suppose that whatever I might have achieved as a writer would have been on the large canvas, and not the small piece of ivory. Writing the life of Tolstoy coincided with other events in life my being sacked from an editorial post at the Spectator magazine, the unravelling of my first marriage and the death of my father. It seems a natural caesura in my catalogue of experiences. So it is with the death of my father, and my visit to Tolstoys grave, that this book ends.

The mind of the older person (I was born in 1950) inevitably moves back to the past, and, since I have the habit of wishing to put things into written form, it was inevitable that I should one day want to put memories of my childhood and early manhood into a book. I have called the book Confessions, not because I think of myself as the St Augustine, or the Rousseau, of our day, but because, without too morbid a sense of unworthiness, I am inevitably made aware of failure, both as a writer and as a human being, as a husband, a parent, a son, a friend.

All perspectives change with time, and nothing has changed more, in my last few decades, than my interior relationship with my parents. Like most people, I carry my mother and father in my head all the time, think of them every day and sometimes, years after their deaths, forget that they are not at the end of a telephone. I meet someone, or have some amusing experience, which makes me think, This evening, when I ring them up, I shall tell them that. This happens often, even though well over a decade has passed since my mother died, and Norman Wilson, my potter father, died in the mid-1980s. One of my recurrent dreams is of spending time with my father, and being aware, as one is often unaware in waking life, of the pleasure his company gave me. Then someone in the dream, sometimes my older sister, says, But you will have to tell him. Tell him what? Tell him that he cant stay forever. Hes As I wake, I realize the truth of the missing word: dead.

In my late adolescence I was most often conscious of irritation in the presence of my mother and father, an irritation which was combined with a sense of shock that, in most of the time I knew them, they did not do anything. Their Chekhovian existence in a remote village in Wales imposed limitations on my adolescent self which, being an adolescent, I saw entirely from my own point of view. It never occurred to me at the time to wonder how they ended up as they did, much of the time unhappy and friendless, and far from anyone who might have understood them. This book is intended, in part, as a resurrection, not only of my earlier selves but of theirs. If, in the following pages, they sometimes seem absurd, it is not because I want to satirize them. They both retained, and passed on to me, a sense of life being comic and tragic in equal doses. Their journey led to my journey, so much of the early part of my memoir will concern their lives, even before I came on the scene.

Twenty years after my mother gave birth to me, I married, so inevitably, the fifteen years as Katherines husband were the background of all my early adult experiences. I was a married man at the age of twenty, and a father of two children by the time I was twenty-four. My wife, Katherine Duncan-Jones, was an academic: a Fellow of Somerville College, Oxford, and one of the most distinguished experts in sixteenth-century literature of her generation. The unravelling of our relationship was probably inevitable. For much of my early married life I was consumed with self-pity and rage, at having been, as I saw it, trapped in this relationship. What was more remarkable, years after the story told in these pages, was the reconciliation that took place between us, no longer as man and wife but as soulmates and friends. The book begins with K in her tragic decline, when dementia laid waste to what was the most playful, sharp and retentive of intellects.

Next page