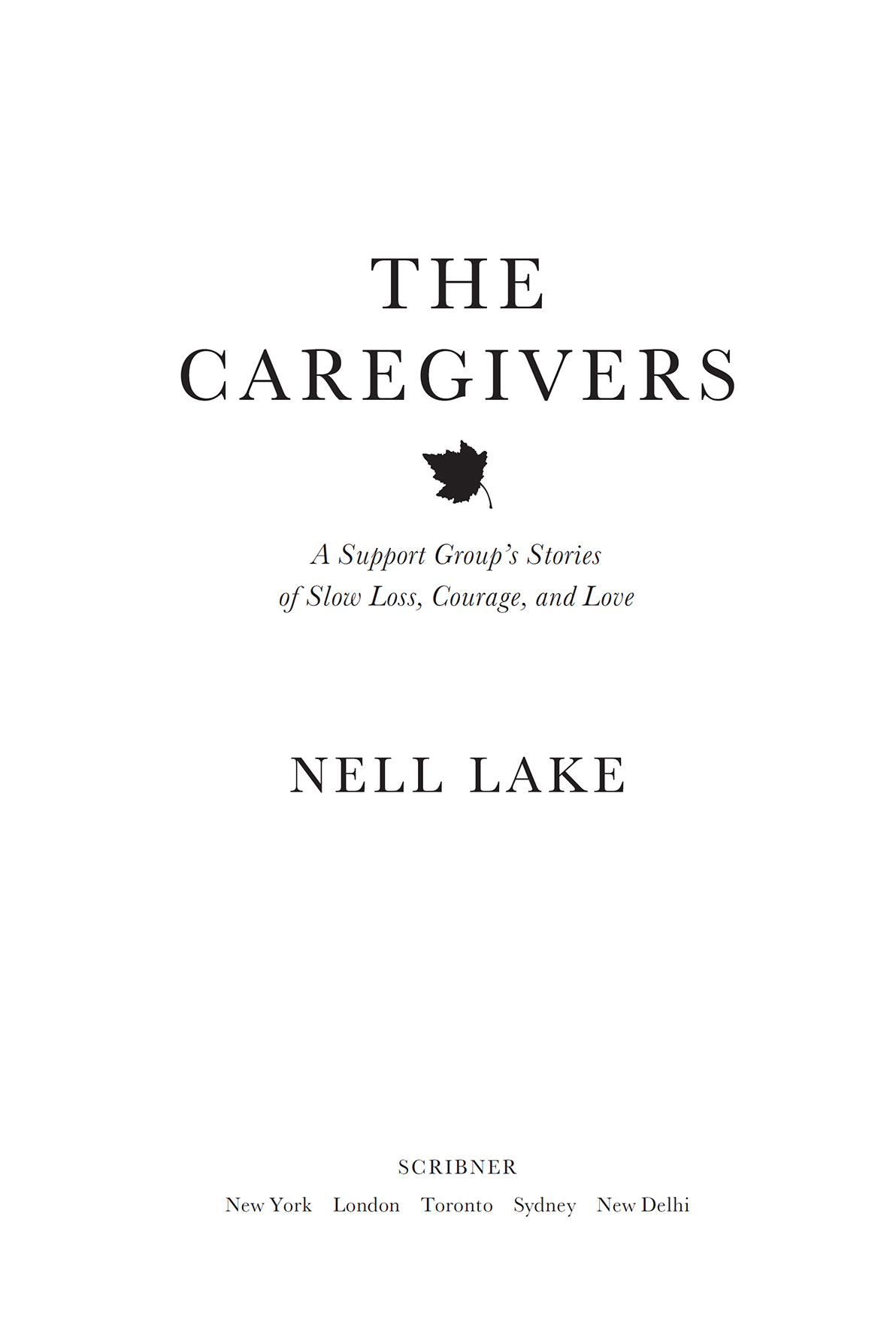

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

For Antonia Lake and Anthony Lake, who taught me to care,

and for Doug, Galen, and Jordan Winsor, who help me remember.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruind choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou seest the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Deaths second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou seest the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed whereon it must expire

Consumed with that which it was nourishd by.

This thou perceivst, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, SONNET 73

PROLOGUE

I remember my grandmother Hildegardtall, slim-framed, her cardigan and shoes sensible but not quite grandmotherly. She was too stylish for thatwallabies, we called those shoes in the 1970s. In a modernist armchair in her study, listening to NPR, she puffed on a pipea pipe! My mothers mother, Hildegard was elegant, German, unadorned, restrained. She had a wide face, high cheekbones, and a gently aquiline nose. I do not remember her embracing me ever; I dont remember sitting in her lap. I do remember the chocolate chip cookies she baked me. She pulled a tin of them from her freezer, layers separated by sheets of wax paper. She held the opened box for me, and I chose one. Cold and hard, loaded with oats and butter, the cookie melted and sweetened in my mouth. She closed the tin.

She strode a mile every day to the center of Litchfield, her Connecticut town, past white clapboard houses with picket fences, and fetched her mail at the post office. She stood by the waste bin and sorted out junk mail. She opened appeals from Planned Parenthood and the Sierra Club and mailed off checks on the spot.

She had filled her big laundry room with supplies for her orderly, practical, and beautiful life: rakes and edge trimmers, bleach and soap, wooden drying racks, winter hats and gloves, seeds and pots. I remember my voice echoing against the walls. She scooped kibble from a drum to a dish shed set on the concrete floor. Her leggy poodle, Justin, gobbled and wagged. She allowed no dust.

I smelled lavender in the sunny upstairs bathroom, and glycerin soap in a stainless steel dish, and the clean sodium of her tooth powder. My cousin and I, when we were ten, lived with her for a summer week. In my grandmothers bedroom, my cousin and I did not jump on the single beds, covered in white, made up tightly. We cleared our dishes away after meals; we played on our own. On steamy days I dipped my hands into the ceramic birdbath my grandmother had placed below the rhododendrons. Shed cultivated native ground covers in the small woods behind the house and left much of the lawn long, in silver and green grasses. Shed had the gardener mow a winding path through the grass toward the vegetable garden in back, where she grew raspberries. My cousin and I ran down the swerving trail and plucked fruit. Our fingers smeared red juice on our cheeks.

My grandmother prized independence and physical vitality. During the time I knew her, she expressed aversion to growing old, particularly to ending up frail in a nursing home. She was uncomfortable with decline and vulnerability, her own and others. She kept brochures from the Hemlock Societythe pioneering death with dignity organizationin a kitchen drawer.

At seventy-eight, in August of my nineteenth year, she learned from a doctor that pain shed been feeling in her back could mean cancer. She needed tests. That same night, in the garage next to the immaculate laundry room, she turned on the car. The next day, an elderly neighbor discovered her.

Its clear to me that, by committing suicide, my grandmother wanted to avoid being an invalid, dependent. It also seems clear that she didnt want to be cared for. My parents and cousins and aunts and uncles reminded one another of this. Still, Ive puzzled, since then, over her death. Ive realized not only the ambiguities of my grandmothers last act, but what she subsequently missedwhat I missed: the intimacy that may come with tending and being tended to. The opportunity to love, to move toward even what frightens us. Perhaps she ducked out to evade the inevitable closeness, the letting go, the being known, the not knowing.

I know well her essential ethic; it has been passed down, in milder form, to me. A worthwhile life, according to my female forebears, is physically vital and wholesomeactive, creative, replete with good cheer and fresh air. My mother, sister, and I savor our vegetable gardens and long hikes and thrown pottery and hand-knit mittens. We attend to homey detail, clear the clutter off counters, and fill our houses with color. We hang laundry on lines because wind and sunshine make the clothes smell best. The sight of white sheets on a bright June day, against blue sky and new green leaves, is good for the soul.

Such physical wholesomeness and beauty feel akin to dignity, grace. Hildegard lived this. She also greatly feared its shadow: the fading of the light, declining vigor, the decay, the messiness of illness and dying. What this meant fundamentally, I think, was that she feared losing control.

My grandmothers conscious fear of the shadow part of life may not have been typical. But because I inherited a similar uneasiness with matters of illness and dying, its fitting, if perhaps not fated, that, twenty-five years after her suicide, I found myself, by happenstance at first, immersed in the lives of a group of people living in that shadow: the members of a support group for women and men tending family members with dementia and other chronic illnesses. In late 2009, Id attended a birthday dinner for a friend and ended up seated next to one Benjamin Cooper. He told me he worked as a counselor at a local hospital, and that he facilitated a support group for family caregivers. I replied that I was a journalist interested in health, mental health, and medicine. Ben invited me to sit in on his group, as he thought their stories were important and illustrated challenges that more and more people face.

He asked the group members permissions, and they welcomed me. They knew similar groups were becoming more common. They seemed eager for recognition of their experiences and said they wanted me to listen, to witness. They said that their support group gave them the solace of intimate, relevant stories. They hoped, generously, that an account of their experiences would help others. Soon I accompanied them in their daily lives, becoming privy to inner and outer dramasthe setbacks, the near-deaths and deaths, the anger and perseverance.

It didnt take long before my outlook widened, and my role as well: If I started as a distanced journalist, I became some hybriddetached writer still, when I could manage it, but also friend and, sometimes, helper to the people I write about here. The shift was unavoidable from the time they welcomed me as a member of the group. I grew to care a great deal about my subjects. Along the way, I drew closer to what my grandmother had fled.

Next page