To Alice and Donald Laird JA

This, my first published work as an illustrator, is lovingly dedicated to my children, Amanda, Greg, Stephen and Michael, adventurers all, and to my own rock-houndmy dear, patient husband, Scott. PC

Copyright 2000 Jeannine Atkins

Illustrations copyright 2000 Paula Conner

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted to any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Atkins, Jeannine, 1953

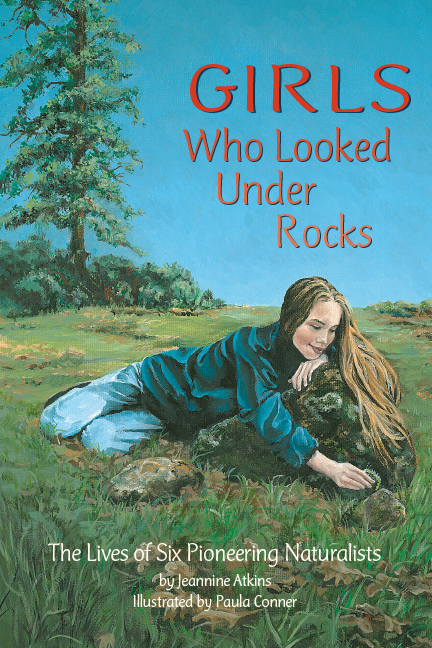

Girls who looked under rocks : the lives of six pioneering naturalists

/ by Jeannine Atkins ; illustrated by Paula Conner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-58469-011-9 (pbk.)

1. NaturalistsBiographyJuvenile literature. 2. Women

naturalistsBiographyJuvenile literature. [1. Naturalists. 2.

WomenBiography.] I. Conner, Paula, ill. II. Title.

QH26 .A75 2000

508.0922dc21

00-008829

DAWN Publications

P.O. Box 2010

Nevada City, CA 95959

800-545-7475

Email: nature@DawnPub.com

Website: www.DawnPub.com

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Design and computer production by Andrea Miles

Contents

Introduction4

Maria Sibylla Merian: 6

Following Butterflies (1647-1717)

Anna Botsford Comstock:16

Among the Six-Legged (1854-1930)

Frances Hamerstrom:24

Secrets (19071998)

Rachel Carson:32

Signs from the Sea (1907-1964)

Miriam Rothschild:40

Life in an Old Lawn (1908-)

Jane Goodall:50

The Dream (1934-)

Introduction

T he six women portrayed in this book all grew up to become award-winning scientists and writers, as comfortable with a pen as with a magnifying glass. They all started out as girls who didnt run from spiders or snakes, but crouched down to take a closer look.

When choosing whom to profile in this book, I was drawn to women who found beauty in unlikely places. I couldnt resist writing about a nineteenth century lady who snatched a wasp at a tea party, pulled her collecting case from the folds of her long dress, and quietly tucked away her prize. In the twentieth century it became more common to find women hunched over microscopes or hiking alone in forests, but a scientific interest in caterpillars, chickens, and chimpanzees was still considered unconventional. These naturalists were too busy watching animals to mind who was or wasnt watching them. They never stopped climbing trees when they grew up.

Maria Sibylla Merian sailed from Holland to South America in 1699 to learn about beetles, butterflies, and some quite spectacular spiders. In a time when naturalists made guides with plants and animals treated separately, Maria painted plants and insects in the same picture. Her work led to a greater understanding of how all kinds of lives depend upon each other.

Anna Comstock was one of the first women to earn a degree in entomology, the study of insects. By writing books and teaching teachers, Anna helped start a movement to include nature study in schools.

Frances Hamerstrom took twelve years of ballroom dancing lessons and wore gowns gracefully enough to become a fashion model, but she gave this up to spend more than fifty years wearing flannel shirts and hiking boots in the mid-western prairies. Frances was one of the first field biologists, those amazing people who spend hours of their days, and years of their lives, watching animals. What they observe helps us learn not only more about the particular animal studied, but more about life in general.

Miriam Rothschild was raised in a mansion, but when she grew up she let the trimmed lawns and elegant gardens grow wild with the weeds that butterflies preferred. As a highly respected entomologist, Miriams concern for the smallest fleas, moths, and butterflies led to a concern for the entire world.

Rachel Carson had a mother who didnt blink, at least much, at finding six-legged creatures in her daughters bureaus. Rachel overcame her shyness to write and speak about the dangers of pesticides. Her best-selling book, Silent Spring, shows how changing one small part of nature can upset the balance of the whole.

Jane Goodall watched bugs in her backyard as a girl. Later she used her curiosity and patience studying chimpanzees in Africa. Her observation that the chimpanzees used tools showed that the differences between human animals and other animals may not be as great as many thought. Jane is now comm itted to helping people around the world see other lives with compassion.

Often these naturalists were the only women among men in their fields. As outsiders, they sometimes questioned things others took for granted, such as a scientists need for detachment. All might have agreed with Jane Goodall that her feeling for animals was a strength, rather than a weakness. These women were passionate scientists. They often worked alone, but they also taught enthusiastically, wrote energetically, and found ways to pass on their vision of how all lives are beautifully connected. Their stories remind us to look and to look harder and then to look again. Under rotten logs or in puddles, there are amazing things to see.

I.

Maria Sibylla Merian

Following Butterflies

(1647-1717)

P

aintbrushes swished and scraped across canvas. The parlor smelled faintly of wood, as blocks were carved for prints. Some visitors were struck by the girl who stood painting between her brothers. In the 1600s, fathers in Germany often taught a trade to their sons, but daughters were expected to learn only cooking and sewing from their mothers.

Its a waste of time to teach painting to a girl, people said. Theres never been a great woman artist. Marias stepfather shrugged rather than argue; perhaps that was because no girl had ever been given lessons, he thought. Besides, he didnt expect to make enough money to give Maria much of a dowry when she got married. It seemed foolish not to give her what he had. He simply advised Maria that her flower paintings might be more popular if she didnt put bees and beetles on the leaves.

But insects were Marias favorite part of a picture. She rarely left the house without a net. She searched through neighbors gardens and around the moat of her village for butterflies and spiders. She brought home caterpillars that were raised for their silk, fed them mulberry leaves, and watched them spin cocoons.

By the time she was thirteen, Maria had decided to specialize in painting insects. Moved by Gods attention to such small beings, she copied the fuzzy texture of an antenna and the tiny holes left by caterpillars nibbling on leaves. Her only tool was a magnifying glass, but her details were so fine that one could almost hear the hum and buzz.

Maria rarely left the house without a net.

As Maria grew older, other German artists admired the beauty in her work and scientists praised its accuracy. She painted moths and butterflies larger than life so that people could plainly see the extraordinary patterns on their wings. Her work brought good prices, but as she watched butterflies perch only briefly before fluttering off to blend into the blue sky, she yearned to see the places where they landed.