These are the researches published in the hope of preserving from decay the remembrance of what men have done and of preventing the great and wonderful actions from losing their meed of glory.

(Herodotus, 440 BC)

This book is intended as a collection of the everyday experiences of frontline soldiers, rather than as a work of military history supported by eyewitnesses. I therefore greatly appreciate and thank all those veterans who, directly or indirectly, contributed personal memories to the book and whose names are noted. Especially kind are those who agreed to allow the use of quotes from their own published memoirs where a particular incident seemed to fit into the narrative.

A number of friends helped in the search for new material and made my task easier at a time when the pool of veterans still able and willing to contribute is rapidly diminishing. Most of my books have started out from my own experiences, extended to those of comrades of my regiment, 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry (1NY), and then reaching out further, through 51st Highland Division, to other units. It is doubtful whether compiling another such book will be feasible in the second decade of the century.

Valued help came again from Canada, thanks to Shelagh Whitaker, Maj. Bob Bennett, Bud Jones, Capt. Tim Flowers, Terry Copp and, before his departure from this mortal scene, George Blackburn. Old Poland spoke through Capt. Zbigniew Mieczkowski and Jan Jarzembowski. Dutch help came from Ger Schinck, Anthony van Vugt and the Soeters family, Jan Wigard, Marius Heideveld, Bea Dekker and Hans Gootzen. On behalf of Germany, Hazel and Manfred Toon-Thorn were again able advisers. And from the USA, Col. Hal Steward and Gloria and Joe Solarz came to my rescue.

Eminent among sources in the UK was the Second World War Experience Centre, where director Cathy Pugh and volunteer Ernest Tate (like me a post-war KDG) found no request too burdensome. Capt. Ian Hammerton, David Fletcher, the late Bill Bellamy, Caroline at Aces High Gallery, Stan Hicken, and the late Rex Jackson were among those who helped me extend my contacts. Jo de Vries at The History Press was always encouraging, helpful, and patient; as was my wife Jai, in whose case the patience had to be inexhaustible. The book was written amid the shambles of packing up, removing from Essex and renovating our new abode in West Sussex, where I shamelessly found it impossible to handle a screwdriver and a keyboard at the same time.

CONTENTS

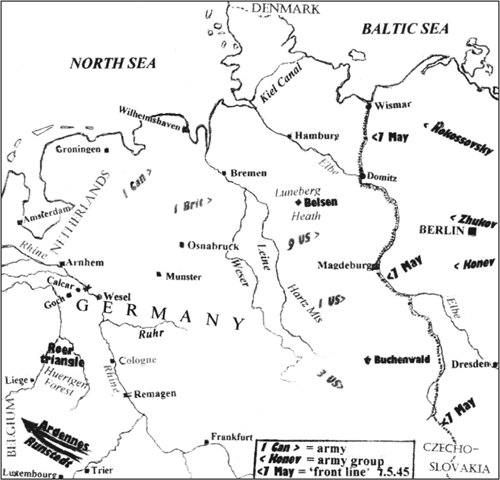

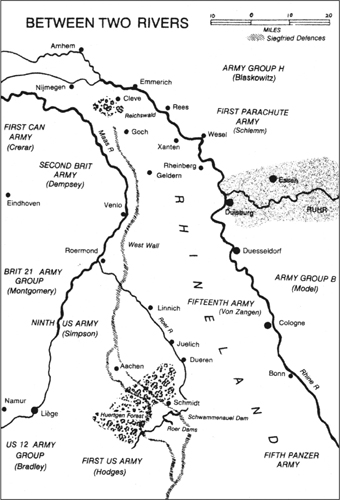

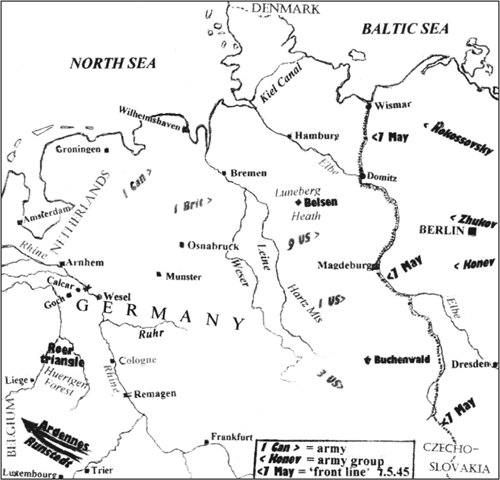

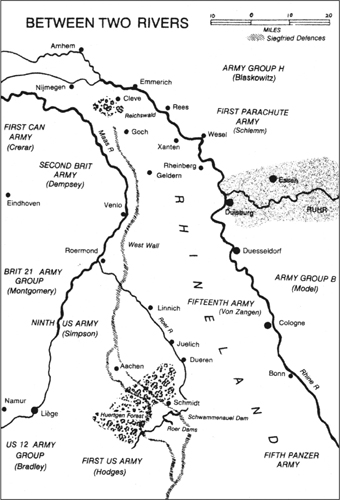

1. North-West Europe, January-May, 1945 (Tout)

2. Rivers Maas and Rhine, 1945 (Whitaker)

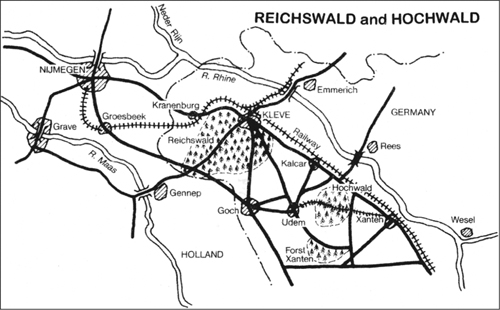

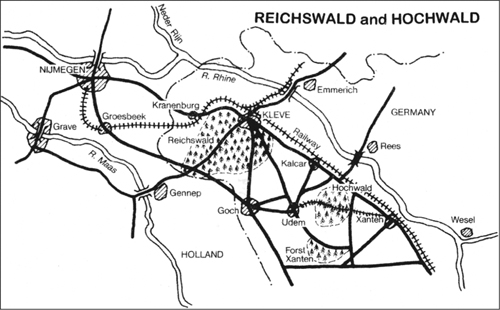

3. Reichswald and Hochwald, 1945 (Hammerton)

Christmas is coming,

the goose is getting fat:

please put a penny

in the old mans hat.

It was the familiar Christmas jingle, but instead of the old mans hat it was a tank troopers beret which was collecting donations of the pretty Occupation Money banknotes. This was going to be the Christmas party of all Christmas parties.

Our tank squadron of 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry (1NY) was laagered in a group of recently liberated Dutch villages; the villagers ecstatically joyful after years of Nazi oppression. But many of the smaller children had never experienced a real Christmas with all the delights and celebrations, toys and sweets, presents and decorations, which we ourselves had so recently known as children.

When we liberated Vught our burly Regimental Sergeant-Major (RSM), George Jelley boy soldier of the First World War and uncle to the raw recruits had driven his jeep into the town centre and found himself surrounded by excited civilians. A local father had hoisted his 6-year-old son into the jeep and onto Georges lap. George had produced a purple-wrapped bar of Duncans blended chocolate (the nearest to milk chocolate in wartime), and offered the bar to the boy. He had been astonished when the boy screamed, struggled and pushed the sweet away.

Now all the village children would share such pleasures. Hastily scrawled (and mercifully uncensored) letters from troopers to mothers and female relatives demanded urgent parcels containing fruit cakes, sweets and childrens toys, which Post Corporal Topper Billingham would chase at the divisional sorting office. Affable Cook Corporal Jack Aris, abetted by Harry Claridge and Scotty, now served reduced rations of dessert at the improvised field kitchen and announced that all the American ration canned yellow cling peaches would be reserved for the big party. Three troopers had already dressed up for the traditional Dutch Saint Nicholas ceremony. Father Christmas would be even more benevolent when played by our gruff, elderly Captain Bill Fox hidden behind a mountainous beard of Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) cotton wool.

Of course there were less joyful aspects to life in Christmas 1944. The war was still going on, and on, and on. Before D-Day, nearly a year ago, we had been paraded to be inspected by the then General Montgomery. Spit-and-polish parades may have been the daily bread of life for the Brigade of Guards, but for wartime conscripts endless and apparently irrelevant peace-time routines caused much moaning and groaning. Nevertheless, we had put our trousers under our mattresses to obtain good creases, blancod our webbing equipment, polished our boots and made ourselves look like real soldiers for an hour or two.

To many of us Montgomery appeared a funny little man with a strange, clipped style of speech. But he handed out free cigarettes so he was a good general. Telling us of the glory days he said that, all being well, the war could be over by Christmas. Subsequently not all went well and it was still not over as we prepared the Christmas parties for our generous Dutch hosts and their children.

We had fought through Normandy, the claustrophobic Bocage and the agrophobic crests south of Caen. We had played a small part in the encirclement and disintegration of an entire German army, and had undertaken the heady race across France and Belgium. It had then seemed inevitable that the war would indeed be over by Christmas. The Germans would never be able to recover and resist, even at the infamous Siegfried Line. But somehow the enemy continued to pose problems in spite of the Allies overwhelming strength and it was not yet all over.

On the positive side, we had been told that we would have three weeks rest in these hospitable Dutch villages. Optimistic and beguiling rumours spread that new formations were coming over from Britain to take over the main thrust of the last battles. Had not the 15th/19th come over to replace our battered 2nd regiment? Had not the entire elite Scottish Lowland Division come directly to Holland to replace the Highland Jocks whom we had been supporting? Good news was triumphing over bad news.

Leave had commenced and usually came in the form of a 48 hour pass to Antwerp or Brussels. We heard that our squadron leader, David Bevan, had gone off to Paris for a day or two accompanied by the colonel and the brigadier. Sergeants and lesser ranks had won lotteries for leave to Antwerp or Brussels. Only skeleton crews remained in the squadron lines. As night drew on, most troopers were sat talking and smoking in Dutch houses or singing and laughing at an Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) concert. Two male troopers of another kind were performing vaudeville acts with a seductive female singer in the borrowed local community hall. Unlucky Tpr Brian Carpenter had drawn the short straw to go on prowler guard among the tanks. An officer and a corporal drowsed in the Orderly Room.

Next page